A meme is both the picture that is worth a thousand words and the few words that can make a thousand pictures—or not.

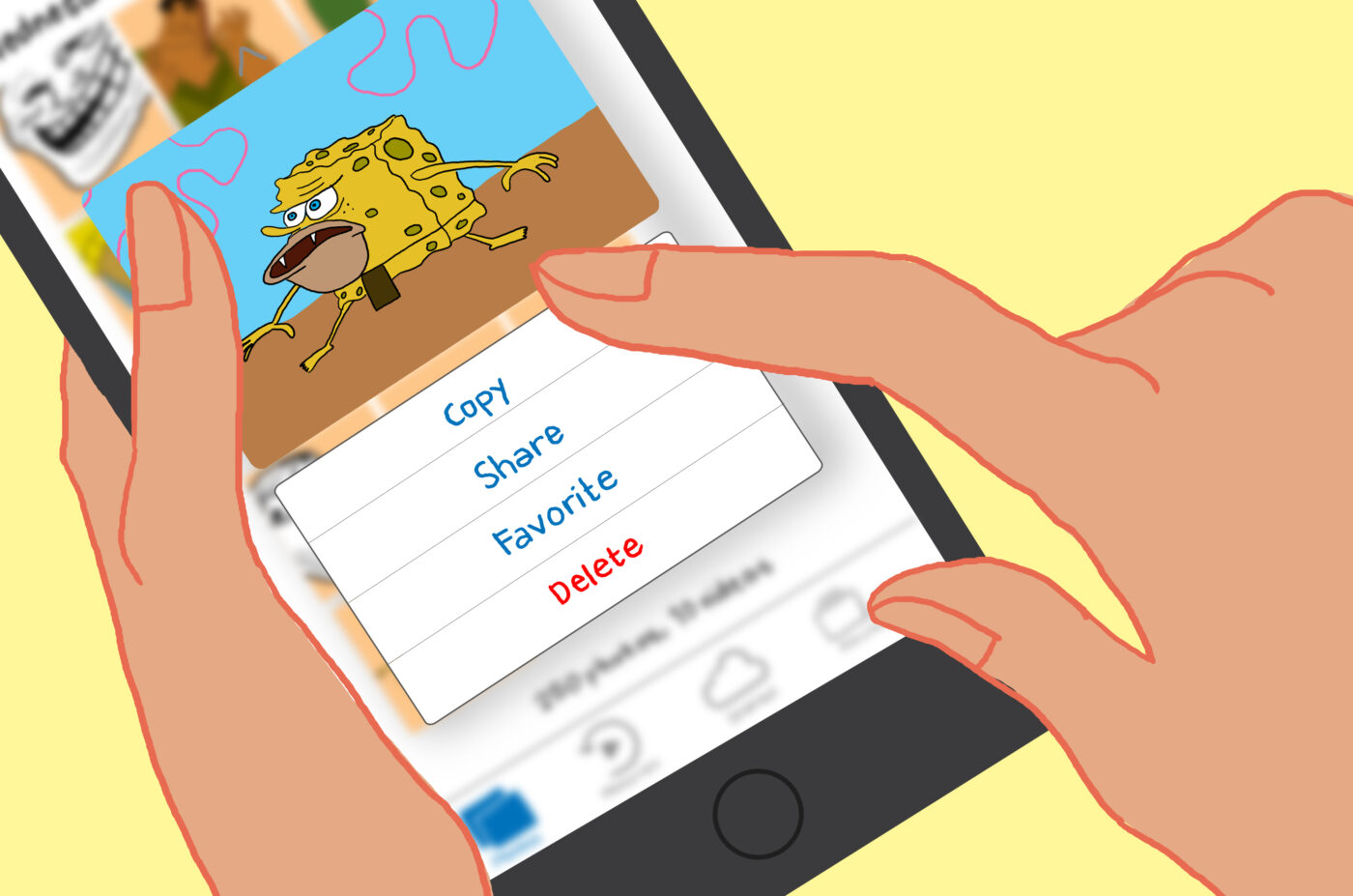

Like hungry brigands waiting by the side of busy trade route, memes ambush and bombard many of us in our own journeys across the Internet, particularly when we travel by social media. They can strike our newsfeeds unexpectedly and boldly. However, unlike bandits out for bounty, Internet memes are seemingly a much more pleasant sight to encounter.

In her 2008 TED talk, memeticist Susan Blackmore explained that memes are bits of information that replicate themselves from person to person through imitation. Memeticists study memetics, a field which explores how ideas propagate among people. Blackmore then continued to say that we human beings have created a new meme: what she calls the technological meme, or the “teme” for short, which is a meme disseminated via technology. The teme is what is commonly known to be the “meme” with a comical picture and text shared on social networking sites like Facebook or Twitter.

This merry friend of ours still has much to share with us. As it acts as a mirror that can reflect our joys and sorrows in an instant, memes have also become a mouthpiece of a generation in constant flux.

To define it is to kill it

Ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins is the first to coin the term “meme” in his bestselling book, The Selfish Gene. Deriving from the Greek mimemes and the French même which mean “imitated thing” and “memory,” respectively, he defines the traditional meme as a living structure that transfers from brain to brain in the process of imitation.

According to Dawkins, memes could be “tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes, fashions, ways of making pots, or [even ways] of building the arches.” He states further that memes and genes are both meant to sustain as well as change humans, but while genes exist for biological evolution, memes, on the other hand, are replicators that allow for cultural transmission throughout generations.

Interestingly, Dawkins did not lay down specificities as to why memes proliferated. Internet memes are steadily reproduced for an unknown—and possibly nonexistent—reason. As The Atlantic writer Venkatesh Rao puts it, the Internet meme is a “meme in the original sense intended by Richard Dawkins: a cultural signifier that spreads simply because it is good at spreading.” It pertains to something that is necessarily vague for it to be universally understood.

While a picture is often described to speak “a thousand words,” the meme goes beyond interrelated ideas and event. A photo of a smirking man with his right index finger pointing on the right side of his forehead, for instance, would mean he’s thinking of something clever. What that thing is though is uncannily up to all of us, making us not just observers, but active participants in the meme experience.

“When you speak of memes, you just feel that it’s a meme. It takes its own being of being a meme in your mind and it can become as weird or not weird as your imagination wants. It’s just what it is for you,” shares Vince Nieva, of the meme page “Ageless Ateneo Memes,” in his talk for Arete 2017: Hayo held last April 5.

The ambiguous quality of Internet memes have been subject to research since 2011. This is what paves the way for a designation of new meanings that creates a sense of flexibility. With every user that is able to add a new twist or plot to the meme, it becomes more amorphous and far-reaching that it connects seemingly disparate ideas into relational entities.

A language of its own

Rao believes that memes are an effect of the “post-everything world” we live in. He explains the complex intertwinement of ideas in our fast-paced world by emphasizing that there is a distinction between the Harambe meme and the actual slain zoo gorilla. This is an age wherein stories are captured while they are still unfolding.

Rapid media technology is going faster than humans can process, which can warp and stunt the emotional reactions to current news. The shock caused by the 2016 American election results led to the creation of many Donald Trump memes pre- and post-elections, which have since been correlated with other memes. In a world freer than ever before, we are both repressed by our technological creations and freed by them.

The universality of meme sharing on social media platforms has made it difficult to continue a single train of thought. In his contribution to the book The Social Media Reader, Patrick Davison states that “viewing and linking…is part of the meme, as is saving and reposting.” Ironically, the ability of anyone to take part in the dialogue, by a multitude of means through memes, has orchestrated cacophonies. However, genuine relationships can still be formed in the ruckus.

“Memes can prove to be a global inside joke amongst ourselves. They can be a way for us to make [some] sense [out] of confusing events and perhaps even cope with personal lost-ness. Memes are a way to get people to connect,” says Alfred Marasigan, an Ateneo Fine Arts lecturer, during his talk in Arete 2017: Hayo.

The practice of meme creation draws up a vague sense of community among those who partake in meme sharing; this creates a mutual understanding of what the meme is—and principally, what it can be. People partake in the definition production that sustains the meme vogue for as long as possible until a new one comes along to dominate the cyber sphere, while the former eventually dies out.

As old memes die, strong emotions from people who share the same experience come together to form a new meme. Interestingly, it has also been a medium for cultural and socio-political critique. According to Know Your Meme, which tracks the origin of memes, the Evil Kermit meme is an image of Kermit and his nemesis Constantine, who is dressed like a Star Wars Sith lord and instructs Kermit to “perform various indulgent, lazy, selfish and unethical acts.”

The meme has been used to point out religion’s underlying crusade tendencies and even question meme culture itself. Other examples include the “nut button,” which evolved from having sexual implications to anything that can trigger one to act strongly, “Arthur’s Fist”—a reaction to situations that are frustrating or infuriating, and many more.

Show and tell

In the technologically-forward society we live in, the way culture is transferred from person to person is changing. Internet memes have revolutionized communication by their nature of transmuting meaning as it spreads. As expressions of our alienation from what our traditional memes can normally keep up with, it is vital to note that we are satirizing something that we cannot fully understand. The world is perpetually moving and memes are constantly angled towards a multitude of narratives.

“Memes are like junk food,” says Andrew Ty, a lecturer at the Ateneo Department of Communication. “Their gratification is immediate and not long-lasting and you end up waiting for the next one very quickly. In the end, [memes] are just one part of this overall tendency nowadays towards viral communication.”

A study conducted at the University of Bonn in Germany provided mathematical models to explain the temporality of memes. Internet memes are just fads, but they are ones that persist by coming back with the same vague appeal and rhetoric—albeit in different forms. Their vogue is infectious to the generation as of now. Soon, however, they’ll be images of the past.

It may seem hard to see memes as something akin to Edo Japan’s “The Floating World of Ukiyo-e,” or even Victorian era post-mortem photographs, but they might just be one of our era’s most distinguishing and awestriking depictions. After all, the meme is representative of a world moving faster than we can understand. As its uncanniness pulls us in, it is likely for memes to one day be an iconic portrayal of our generation.