On Labor Day, the banners tied to the Mendiola footbridge change multiple times. They change along with the flyers and the protesters who distribute them. They all say they want contractualization to end, that they want fair wages, while calling out unfair conditions in the workplace. And yet, they protest separately. This year, there were four separate protests in Mendiola, each with representatives occupying a different place in the spectrum of the Philippine Left.

Traditionally, when one speaks of the Left, one is easily reminded of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), its armed segment, the New People’s Army (NPA), or its political arm, the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). The CPP-NPA-NDFP, after all, remains to speak on behalf of peasant-based armed struggle in the country, openly espousing the Maoist rhetoric of seizure of state power through power from below. However, over the decades the Left has come to develop a more dynamic identity in the Philippine political consciousness.

History of the Philippine Left

“There are different definitions of Leftism around the world, based on the country’s situation, conditions, and priorities,” says Political Science Department lecturer Hansley Juliano.

The 1930s saw the formation and eventual merging of the proletarian groups Partido Sakdalista and the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP), in the face of burgeoning poverty in the countryside as well as among the urban working class. Both groups were vocal in their opposition against the ruling elite class, which then found its representative in the Partido Nacionalista, the party of would-be presidents Manuel Quezon and Sergio Osmeña. Historian Patricio Abinales writes that in clashes against these opposing actors, the Sakdalistas and PKP with their bolos, machetes, and homemade guns, would go up against an American-supported, well-armed Constabulary.

Support from the United States (US) also meant that the Philippine Commonwealth took after the anti-communist rhetoric of the US. Anti-communist action was relatively halted for a while during World War II, however, as the PKP’s armed faction, the Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon (Hukbalahap), proved itself to be an effective guerrilla army against the Japanese.

After the war, the Hukbalahap and the PKP would be subject once again to discredit, first as illegitimate guerrilla units and later on, as threats to the Philippine state, then only newly-granted sovereignty by the US. The government believed that Philippine communists wanted to seize state power, leading to further discrediting the Philippine popular movement. The debacle would culminate in the capture of former Hukbalahap commander Luis Taruc, under the guise of peace talks with the government of Ramon Magsaysay.

The communist movement would only regain wide support during the Marcos dictatorship. Jose Maria Sison, then a young cadre and founder of the revolutionary youth group Kabataang Makabayan, split from the older PKP (known now as PKP-1930), to form what is now recognized as the CPP. Sison broke away from the older leadership due to disagreements regarding the approach to the struggle—he was a strong adherent of the Maoist strategy of protracted people’s war from the countryside.

The CPP – and the subsequently founded NPA – reached the peak of its membership under the Martial Law era, when it presented itself as a revolutionary alternative to the abuse and corruption of the Marcos dictatorship.

After the toppling of the dictatorship, the CPP experienced internal schisms which severely weakened and fragmented it. From these splits against those loyal to the party orthodoxy or “reaffirmists,” many different Leftist factions or “rejectionists” emerged, including insurrectionists in the Rebolusyonaryong Partido ng Manggagawa and social democrats who would eventually compose groups such as Akbayan.

Divide between activists

According to Juliano, activists now do not think the same way as those in the past, which creates a gap between the two generations.

This gap was evident during the vice-presidential elections last year, when many of the older activists blamed millennials for former senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr.’s near-win. However, statistics showed that it was mostly the older generation who preferred Marcos. This issue posed a question on the unity between the activists of then and now, and the effectivity of the activists on the political views of the older generation.

The gap could also stem from the not-so-straightforward evolution and development of Leftism, due to its different traditions and groups. Between the two main traditions—the social democrats, which are perceived by some as being friendlier to the Liberal Party, and the national democrats, which are said to be more inclined to the underground way—the former is more influential in the Ateneo.

However, Juliano cites the Comparative Voter Share in the years 1998-2010, which shows that there are still more Filipinos who align with national democratic ideals. “In the Ateneo, Leftism is sympathetic to the struggles of the communists outside,” Juliano explains, “but [they] don’t necessarily agree with the tactics.”

All-in-all, an evident divide between activists, especially those under the Left spectrum, is prevalent and present until today.

Prospects for the Left

Despite the increase in social awareness among the youth and the prevalence of ideologies, Juliano states that Filipinos still need more motivation and mobilization to unite and become more active in political affairs.

This translates to the country’s political situation. Despite the plurality in the Philippine Left, leftist groups are relatively weak in political arenas, especially in elections and governance. Most groups are able to penetrate electoral office only through the party-list system. In recent administrations, leftists have been able to penetrate executive positions. Under the Aquino administration, members of Akbayan held key positions. National democrats, on the other hand, were appointed to several cabinet positions under President Rodrigo Duterte.

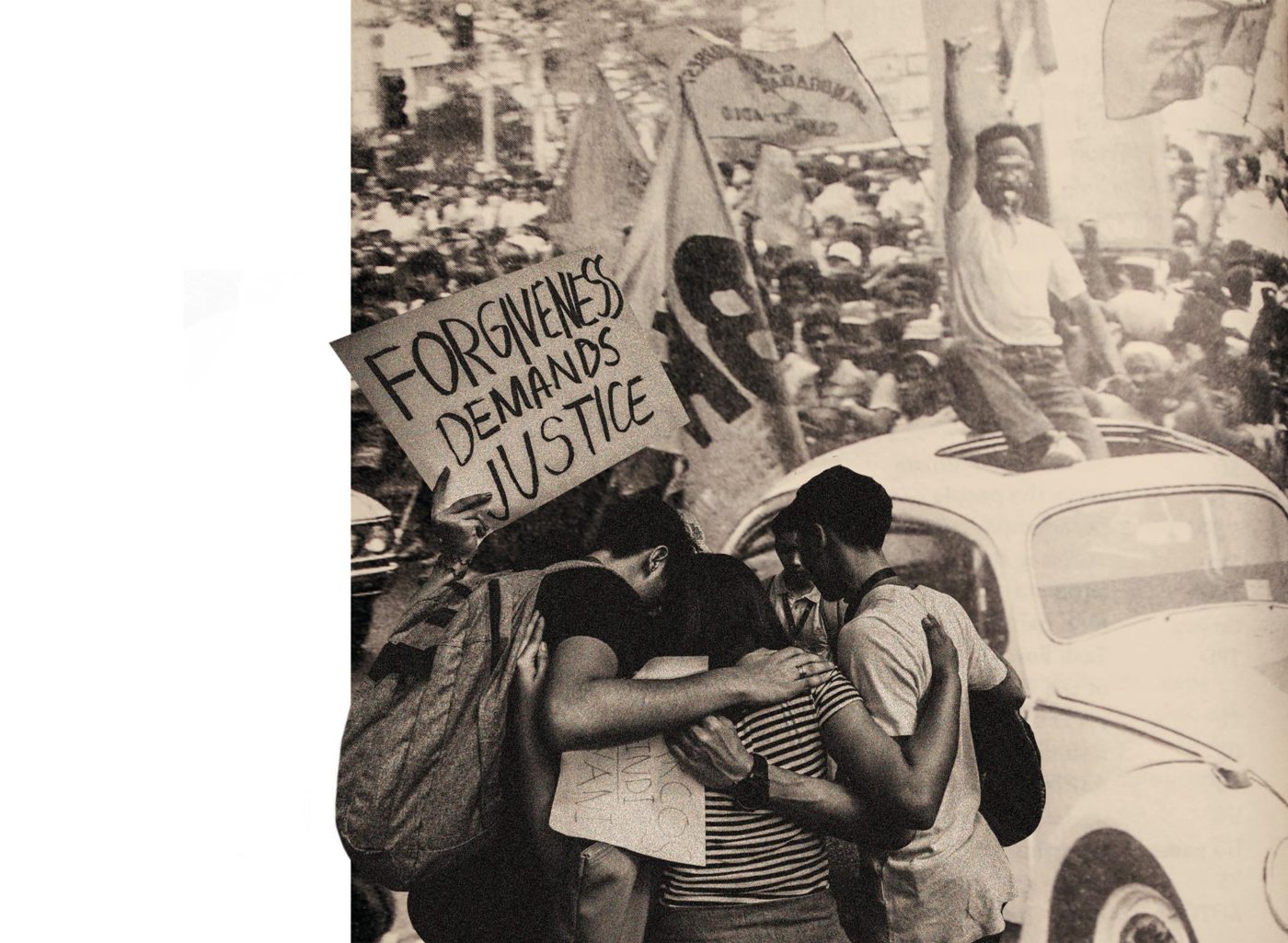

Despite these developments, the challenge of mobilizing and politicizing the vast majority of Filipinos still stands. While leftist groups are able to mobilize sectors such as laborers, peasants, and the youth as seen in the large turnout during this year’s Labor Day mobilizations, many more Filipinos remain passive onlookers. This hinders the Left’s ability to potently challenge elite rule in the country.

Juliano believes that the national political situation is reflected in the political climate of the Ateneo. He cites the issue of the recent student elections in the Ateneo, wherein the turnout of voters was still the lowest. Only a miniscule portion of the student population is participating in the student government’s affairs.

“Our responsibility [as students] is not only to study our disciplines. We must also study society and our place in it, so when we graduate, grow old, enter our own sections, we [will be] equipped with the tools to understand what our sectors need,” Juliano states.