Journalists and other media personnel have been hard at work in documenting the happenings in our country at present, from the rapidly increasing death toll of President Rodrigo Duterte’s war against drugs to the recent string of political controversies, including the burial of Former President Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

What is perhaps not immediately obvious in this scenario is the great deal of danger and risk involved. In dealing with such volatile issues, there is a possibility for the journalists—and at times, even ordinary people who are merely sharing their own opinions—to be stigmatized by online communities, shunned by fellow friends and colleagues, or even attacked by radicals and fanatics. Some people are quick to criticize and raise pitchforks when others are merely exercising their freedom of expression, and this is the unfortunate reality we face in our country today.

In many ways, there are chilling similarities to Martial Law, which is considered by many to be one of the country’s darkest and most trying times. Censorship became one of the most effective and crippling tools at the Marcos administration’s disposal, effectively curtailing the freedom of not only the media, but of ordinary Filipino citizens as well.

Absolute control

It is important to first distinguish the kind of censorship present during the Martial Law period and separate it from what we know of today. As History Assistant Professor Jose Ma. Edito Tirol, PhD, puts it, “censorship during Martial Law was part of a structure designed specifically to control access to information, and therefore, limit people’s reasons and options for actions.”

To put things into perspective, the first Letter of Instruction was issued on September 22, 1972—signed immediately a day after the declaration of Martial Law—and it ordered the Press and Defense secretaries to take over and control nearly every outlet of the media. “Periodicals classified as anti-Marcos [were shut down]…at the same time, leading media men were arrested and detained,” Rosalinda Pineda-Ofreneo details in her article “The Press Under Martial Law,” published in 1984. She adds that only a select number of publications remained, all of them “controlled by persons who identified with or [are] close to the Marcos administration,” such as the Philippine Daily Express, Times Journal, and Bulletin Today.

In the following years, the administration came out with more initiatives to control the media even further. The Department of Public Information (DPI) announced two orders which “stipulated that all media publications were to be cleared first by the DPI and that the mass media shall publish objective news reports,” while the second order “prohibited printers from producing any form of publication for mass dissemination without permission from the DPI,’” as outlined by Pineda-Ofreneo.

Several regulatory boards designed to expand the control beyond print media were also established soon after. The first of these committees, the Mass Media Council, was abolished and recreated numerous times over the years, but the principal goal of curbing public opinion and press freedom stayed the same. From the short-lived Media Advisory Council to the self-regulatory Philippine Council for Print Media, the censorship and repression of the media stayed strong and imposing for a significant amount of time.

On campus

While universities such as the Ateneo still maintained some degree of academic freedom back then, they were not untouchable either. “Student publications were completely banned in 1972,” affirms Cristina Montiel, PhD in her book Down from the Hill (2008). “A year later, the ban was lifted with restrictions,” she adds, but by then, the damage had already been done.

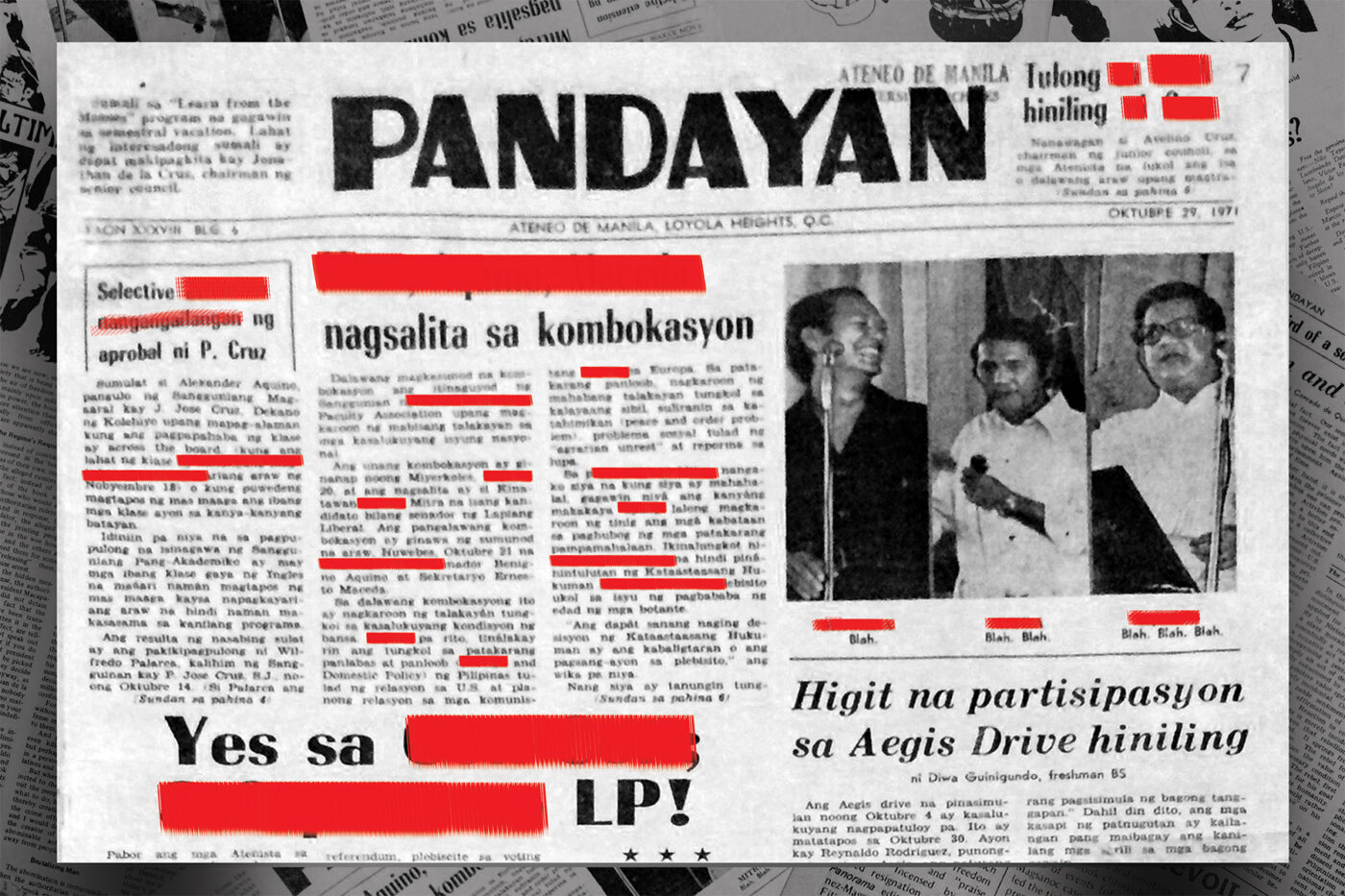

As is to be expected, the censorship rulings changed the landscape of the Ateneo’s student publications drastically. Heights stopped publishing issues entirely. The GUIDON was rebranded as Pandayan a few years beforehand, but its noticeably more radical and politicized tone did not receive the approval of College Dean Jose Cruz, SJ, eventually resulting in the publication’s funding being cut. Nevertheless, some of the writers were determined to continue. This resulted in the formation of the Rebel Pandayan, an underground publication containing several articles that were distinctly anti-Marcos and against Cruz’s administration. The publication was able to effectively express the students’ desires for social change, but most of its writers eventually left the Ateneo after two issues, voluntarily or otherwise.

The ban on student publications was lifted in 1973 and The GUIDON “was one of the first campus papers in the Philippines to be revived during Martial Law,” as noted by Montiel. Particularly important to consider in this time period is the shift in article content and subject matter. Articles that discussed prevalent social issues dropped down dramatically to roughly 16% from the previous 50% pre-Martial Law. Filipinization and student politics remained prominent topics but student activism, political discourse, and anti-Marcos sentiments were nowhere to be found.

The abundance of stale, run-of-the-mill articles published at this time were attributed by many to the efficacy of Marcos’ censorship measures. Political topics were avoided for fear of suspension, expulsion, or arrest, articles were heavily edited and were required to go through faculty advisers, and students were forced to either blanket their social concerns in several layers of subtleties and symbolisms or find other avenues to do so instead.

Fortunately, toward the latter years of Martial Law, the Marcos administration’s grasp on the media weakened, and the enforcement of censorship eased up as a result. Matanglawin, which first started as an underground publication in 1975, was one of the bigger influences in reinvigorating the Ateneans’ drive for sociopolitical discourse. The GUIDON followed suit eventually, as students “felt more courageous about writing on more relevant social issues,” according Montiel.

Aftermath

The Marcos administration was put to an end after the 1986 EDSA revolution, and eventually, the laws and rulings on censorship were repealed. Since then, several laws have been passed that are meant to protect and preserve the media’s freedom and rights.

A prime example is Republic Act 7079, otherwise known as the Campus Journalism Act of 1991. Among the provisions listed are the rights and functions of student publications, and more importantly, the security of tenure—a much needed response given the unreasonable consequences faced by student writers during Martial Law. The provision states that “a student shall not be expelled or suspended solely on the basis of articles he or she has written…in the student publication.” At present, The GUIDON, Matanglawin, and Heights remain as the Ateneo’s official student publications, each with specific functions designated by the student handbook and in compliance with the law.

With that said, censorship has unfortunately also endured through the years. While it has not been nearly as big of an issue since Martial Law, its effects are very much still apparent.

One such issue that has been getting more traction with the Filipino community nowadays has to do with social media and online etiquette. The recent Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 met a great deal of backlash from many different sectors, particularly due to one of its provisions criminalizing online libel. In an 2013 article by former University of the Philippines Manila Professor Teresa Jopson, she says that “the state is unable to police cyberspace uniformly, so that the law may be applied unevenly against its critics.” Furthermore, she adds that “the provisions on libel in the [act] could heighten the online self-censorship of journalists, artists, and the public.” The intrusive and unorderly ways by which the law was intended to be implemented were eventually ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, but the controversy and uproar caused by this incident are enough to prove that the fight against censorship is far from over.

Breaking the silence

Shutting down the media through extreme censorship measures effectively also silenced the vast majority of the people, as they were left isolated with little or no outlets for speaking up against the Marcos administration. This culture of fear and silence fostered by Martial Law has been ingrained in the Filipino people over the years.

What Jopson calls “multilevel censorship” is now seemingly the norm in our society, with some writers going through extensive self-censorship just to cater to the publishers’ demands. She believes that “normalized repression, with impunity, and misinformation and lack of information make media practitioners silent by intimidation and the public by ignorance and apathy.”

Lately, people have been flocking to social media as a platform that allows seemingly unshackled and censorship-free exchanging of information for journalists and non-writers alike. However, a closer look at the situation reveals the double-edged nature of the freedom we so desire. A yearly assessment conducted by the independent watchdog organization Freedom House shows that as of 2015, “violent attacks, harassment, threats, and legal action against members of the press [remain] serious problems.” The recent presidential election also comes to mind, especially with the numerous cases of cyberbullying and harassment caused by some overzealous supporters.

In the end, Tirol emphasizes that “Philippine media today is much freer compared to the way it was thirty years ago.”

“Although this has led to some abuse on the part of media…I’d like to think that journalists on the whole are more responsible,” he says.

Indeed, blood and tears were shed by countless martyrs in fighting for the freedom that we have right now. In the spirit of the “Ateneans Don’t Forget” campaign, we too should remember that we have our own roles to play in making sure this same freedom will not be abused or trampled upon ever again—not by any dictator and certainly not by our own friends and countrymen.

Written by someone who wasn’t even there, who read and researched from biased material and who has an agenda.