It was at this year’s World Hip Hop International (WHHI) dance competition—more popularly known as Worlds—where everything changed for local hip-hop. In Las Vegas, the Philippine dance crew A-Team emerged as the champion of the MegaCrew Division, lighting up social media with roars of support from fans and fellow dancers all over the world.

It was a remarkable moment, especially for a country where dance, particularly hip-hop, has had difficulty being taken seriously as a profession. This doesn’t seem to stop the local dance community, though, from growing by leaps and bounds. In fact, if the international attention heaped on the A-Team’s victory is anything to go by, Philippine hip-hop groups are slowly taking the world stage by storm.

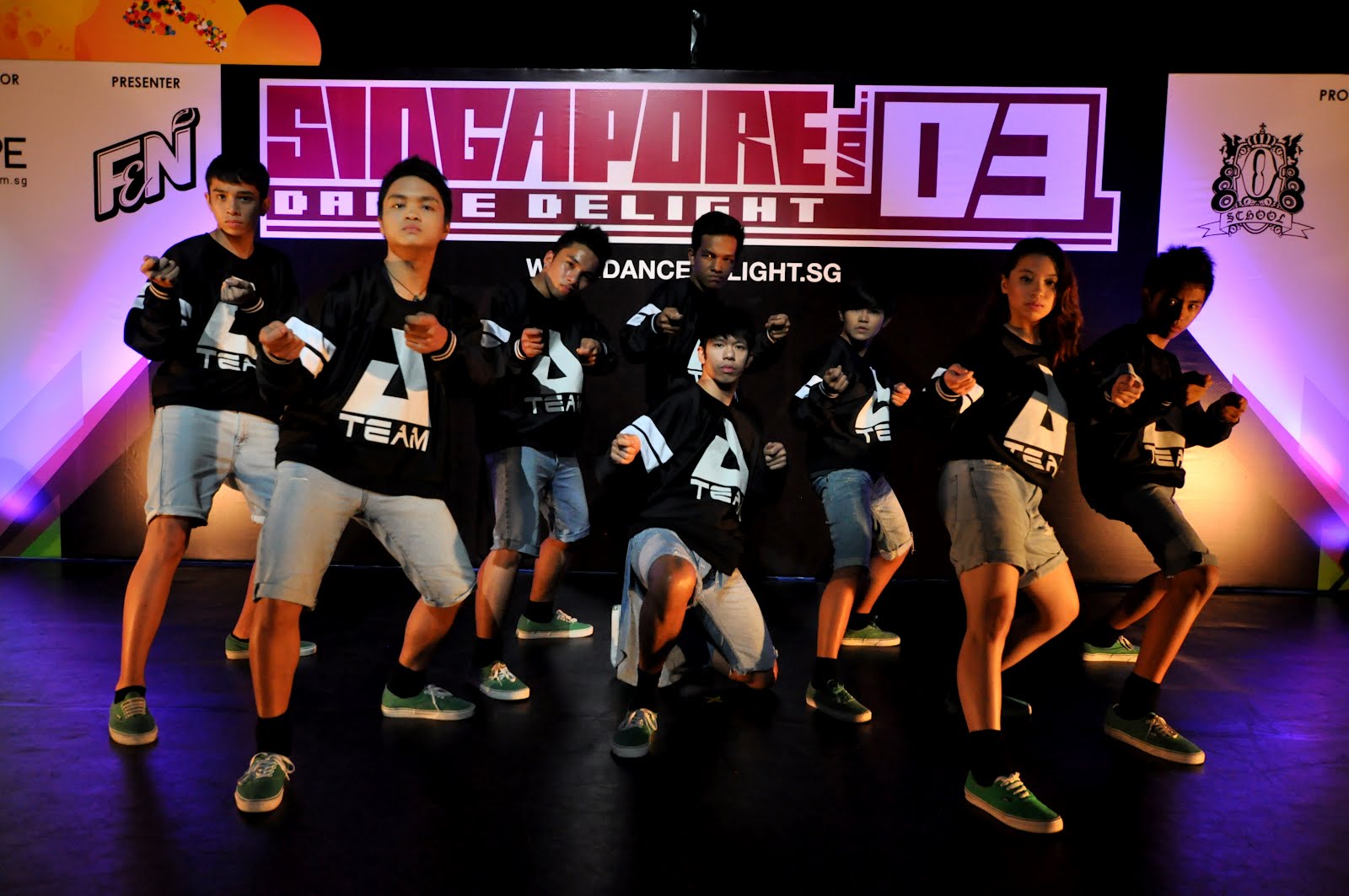

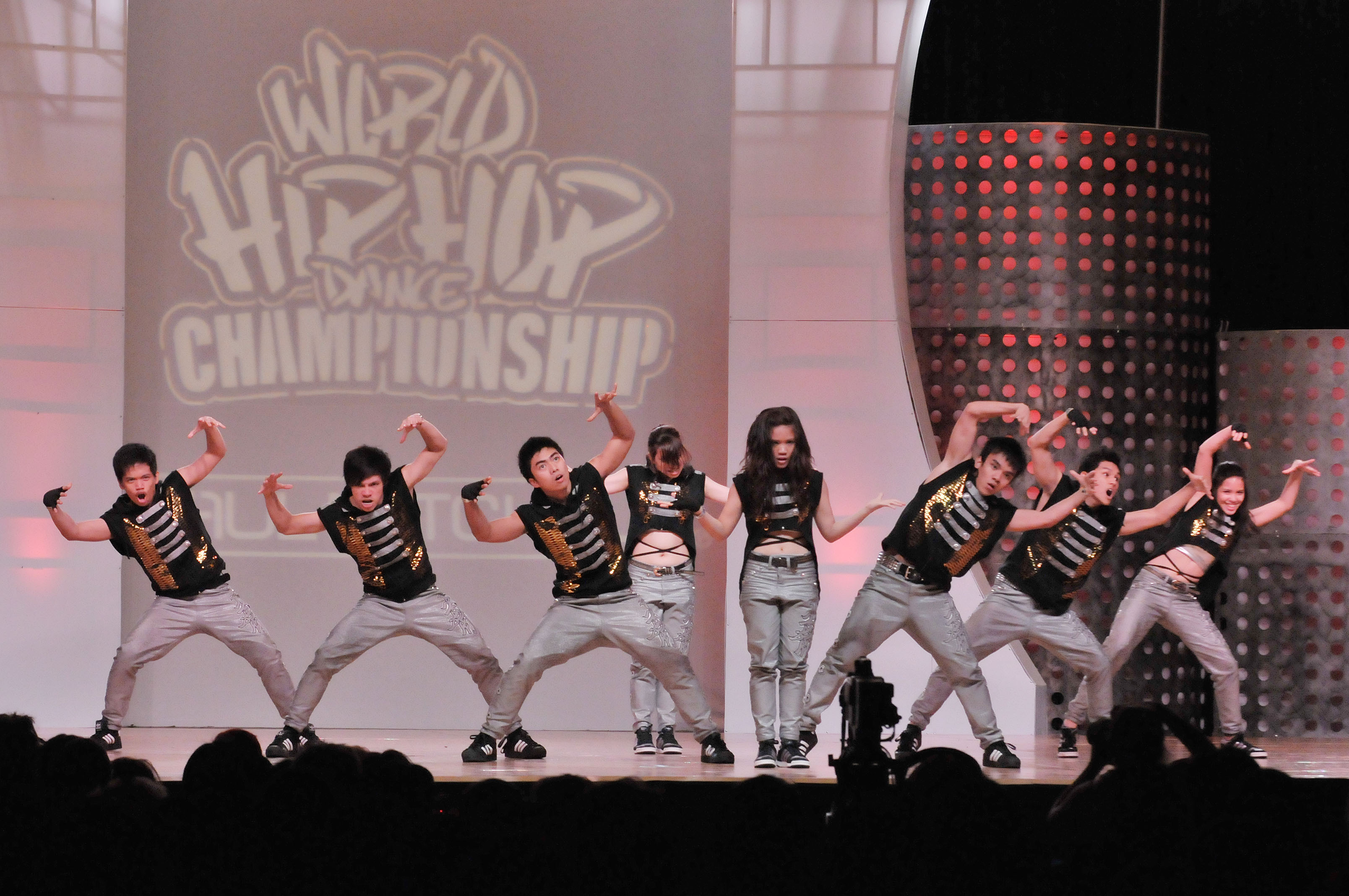

STEP UP. Local hip-hop groups have consistently been dominating various international competitions and exhibitions over the years. (Photo from onlywilliam.blogspot.com)

Center stage

The A-Team’s victory also marks the first time a Philippine group has won gold in the MegaCrew Division, which requires crews to be composed of 15 to 40 members. Other Philippine teams have taken home the gold medal for the Adult Crew and Varsity Crew Divisions in previous years, such as The Crew in 2012, the Philippine Allstars in 2006, 2008 and 2009, and C.I.D.G. in 2007.

The A-Team boasts an impressive 30 members from a variety of schools like the Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University, the University of Santo Tomas and the University of the Philippines. One of its members, communications technology management junior Immanuel Pacis, estimates that they trained for around a thousand hours to perfect their winning routine. “I had to balance writing papers and going to school and going to training and conditioning… So I really had to sacrifice sleep in order to accomplish my requirements,” he explains.

“A lot of young dancers from high school teams, they dance to get to Worlds or to win,” says European studies senior Suzie Agustin, who herself competed in Worlds as a member of Legit Status from 2010 to 2012. “If you really get into the local dance community and go underground to see the freestylers, the battlers, you see that dancing is so much more than winning.”

As a freshman, Agustin entered the Company of Ateneo Dancers (CADS) with the unique advantage of being a Worlds veteran. In 2009, she watched as Vimi Rivera, her high school dance coach at the Assumption College Dance Troupe and the coach of La Salle Green Hills’ team Airforce, gathered the seniors from both teams to form the first varsity team the Philippines ever sent to Worlds. The following year, she joined the team that would eventually come to be known as Legit Status.

Five intensely competitive years eventually took their toll; Agustin remembers a time when she stopped altogether because she felt she couldn’t pursue dancing as a career. After some time, she realized that she couldn’t let her fears get the best of her. “It’s not like before, when it was about me, me, me. Right now, my drive comes from the dancers and that special bond with the team, because we look out for each other, we have a common purpose.”

STEP UP. Local hip-hop groups have consistently been dominating various international competitions and exhibitions over the years. (Photo from Dancemanila.com)

Behind the curtain

Despite the fact that the Philippines has been blazing a trail in the world hip-hop arena, several misconceptions about the art form still exist locally. Not many see the local hip-hop dance industry’s potential for growth, but Agustin certainly isn’t one of them.

“If you go to Worlds and meet other dancers from other communities, like Japan or New Zealand, you see that their governments really support them,” she says. “In the States, it’s really an industry.”

Perhaps this is why it comes as a surprise that, despite all of the success that Filipino teams have experienced in international competitions, something similar has yet to happen here. “I hear foreigners say that they want to come to the Philippines because they think that it’s a dancing mecca, and they get sad when they find that we’re not well-supported,” recalls Agustin.

A career in dance can actually be a financially stable one—just take Jesse “Reflex” Gotangco’s (BFA AM ‘10) word for it. A hip-hop instructor, choreographer, judge and winner of the solo category of the 2012 R16 Korea World B-boy Masters Championship, he certainly knows the rigors of translating one’s passion into a profession.

“You just gotta know how to work, work hard, and know how to get into the different aspects of dance,” he explains. “Most people think… I’m a dancer, I’m just gonna dance, I’m gonna wait for people.” Gotangco does precisely the opposite, taking on a multitude of gigs, such as coaching CADS, teaching breaking and streetdance classes in the Ateneo, and hosting events.

He also notes that hip-hop often gets a bad rap from the way it is portrayed in the media. “MTV today, it’s like rappers talking about hoes, drinks, drugs, stuff like that, you know?” complains Gotangco, adding that for him, this isn’t real hip-hop.

If anything, hip-hop can be a positive influence. “For me, hip-hop teaches self-worth and ownership, which I think is really important,” he shares. “The art form promotes individuality and originality, and I think a lot of people today need that type of confidence.”

STEP UP. Local hip-hop groups have consistently been dominating various international competitions and exhibitions over the years. (Photo from Pacificrimvideo.com)

Spotlight

When all is said and done, there will always be more to hip-hop than the freestyling and battling that so often characterizes it. For Agustin, dancing in high school was an escape. “When you’re a teenager, you have all these frustrations, and dance always felt like something constant, something to come home to,” she says.

According to Jazz Zamora, a professional dancer and coach of the LMN dance crew, one of the official Philippine representatives in the Varsity Division of Worlds 2013, “People forget to see the simple reason, and that is love for [dance]. A lot of people, I think, are just in it for a shot at fame, but now, a lot of people are here to express, learn and share and spread the community.”

With the constant evolution of dance trends, it’s easy to get left behind. “You have to really be knowledgeable about what’s happening, and you have to keep developing with the community,” adds Zamora.

Dance can even serve as a common language; Zamora recalls competing at the Singapore Dance Delight with Tha Project last summer and being welcomed onstage by a crazed audience that knew nothing about them except that they came to dance. “I think it was my most fulfilling performance in my 10 years as a dancer, because it was a kind of personal validation; it’s the feeling that you’re part of something right.”

He believes that the Philippines no longer has anything to prove to its neighbors. “It’s not a question anymore of the Philippines being a dancing powerhouse in terms of international competition, but I think what these victories does is they put a stamp on it and solidify it,” says Zamora.

Pacis agrees with this sentiment, crediting teams like the Philippine Allstars with opening doors for the A-Team. “I think [our victory] just gave the hip-hop teams here in the Philippines more confidence, thinking [that] A-Team won nga, and before, we were just on their level.”

Agustin, on the other hand, sees the A-Team’s victory as a challenge. “There are no more excuses,” she says, referring to their success in overcoming the disadvantages of being a Philippine team. Filipino hip-hop dancers now have big shoes to fill, regardless of the lack of institutional support and respect for the craft. If the successes of today’s champions are anything to go by, there is nowhere else for the local hip-hop scene to go but up.