This National Heroes’ Day, Beyond Loyola revisits Ateneo in a time of turmoil and the lives of students who have truly gone down the hill.

TUCKED BEHIND a nondescript gate along Quezon Avenue is the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, a memorial dedicated to honor the fallen heroes of the Marcos dictatorship from 1972 to 1986. The 1.5-hectare area, managed by the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Memorial Foundation, contains a museum, library and research center.

There are no other visitors when we drop by. The first stop in our tour is a 35-foot monument of a woman. She is Eduardo Castrillo’s Inang Bayan, towering over a man who personifies the martyrs of the Martial Law.

Nearby is an imposing wall of black granite, the Wall of Remembrance, where the names of 241 martyrs and missing are etched. Some have been shot, others tortured, and many have become desaparecidos (the disappeared), their fates unknown to this day.

“Karamihan dito, mga kabataan talaga, kasi sila ang kumilos (Many names here belong to the youth, because they fought),” our guide points out, estimating 60%.

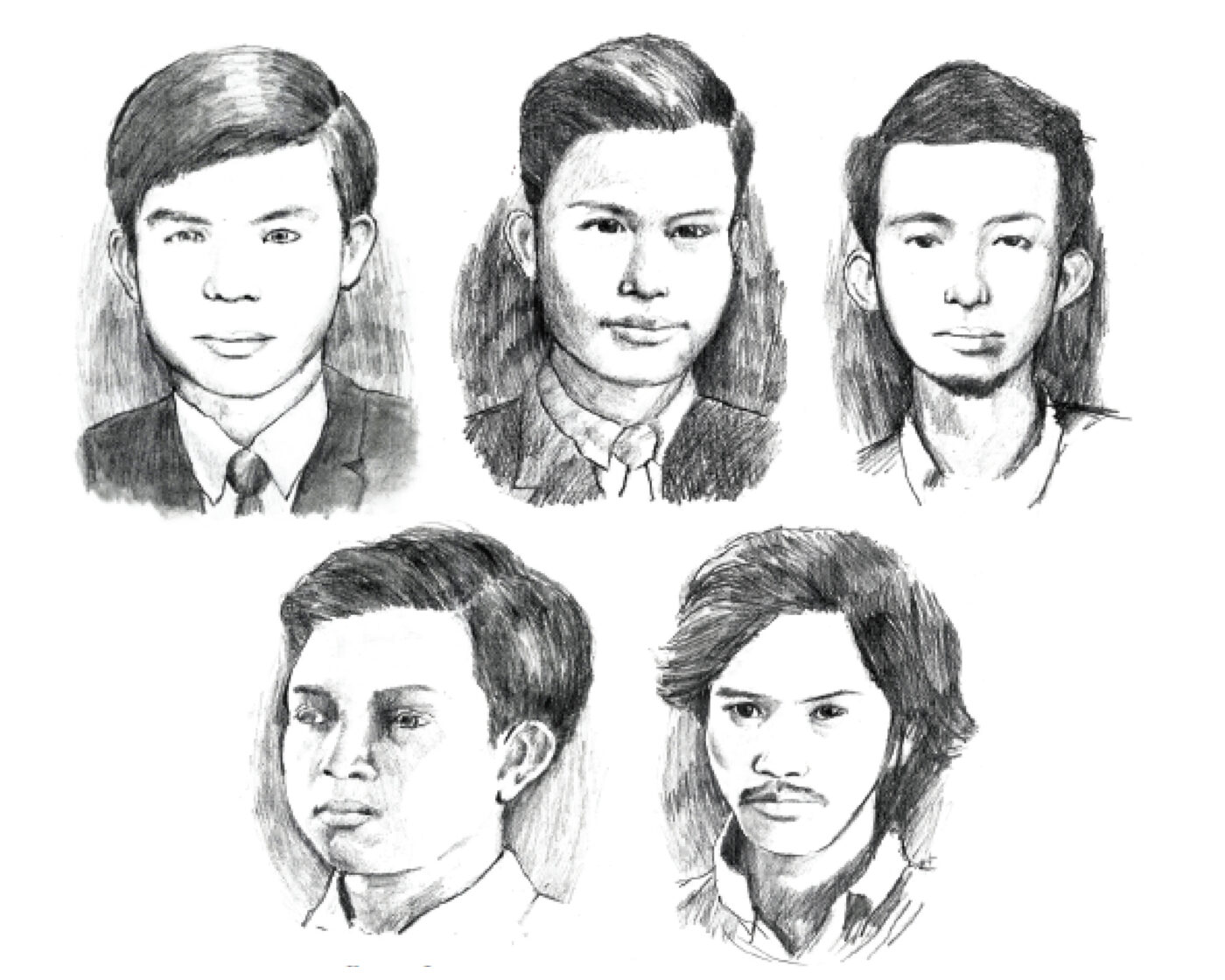

At least 11 of the names belong to Ateneans.

University unrest

In a permanent indoor exhibit, there are photos and short biographies of students who rallied against former President Ferdinand Marcos. “Students as a group are naturally organized… They have logistics, they have pocket money, which farmers and workers may not have,” explains Cristina Montiel, PhD, professor at the Psychology Department, and author of the book Living and Dying: In Memory of 11 Ateneo de Manila Martial Law Activists (2007).

“These [were] the people who will be your leaders later on,” says Mathematics Department Professor Norman Quimpo, PhD, who was already teaching since the 1970s. He adds that the student desire to be involved was strong then, and not joining in would elicit feelings of being left out.

Across universities, activism was rampant as students arranged and joined rallies. Organizations like the Sandigan ng Pilipinas and Lakasdiwa were moderate, while Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan sa Loyola (SDK-L) and Kabataang Makabayan-Ateneo (KM) were radical and believed that force was necessary for change. The first radical activist group in Ateneo, Liga ng mga Demokratikong Atenista (LDA), was established in 1970. One of its co-founders was Ferdinand “Ferdie” Arceo, an AB Humanities major from 1968 to 1972.

Other Atenean martyrs such as Lazaro “Lazzie” Silva Jr. (BS ME, 1970-1971) and William “Bill” Begg (AB, 1968-1972) were active members of SDK-L and KM. Artemio “Jun” Celestial Jr. (AB EC, 1970-1972) was involved with Student Catholic Action and secretary-general of the student government. Their lives are detailed in Montiel’s book. The book also mentions martyrs who did not spend their collegiate years in Ateneo, like Abraham “Ditto” Sarmiento Jr. of the Ateneo High School Batch ‘67, and Dante Perez, who spent his grade school years and first year of high school in the Ateneo.

“I’d say the administration was more inclined to support the moderates,” Quimpo recalls. His brother Nathan (AB COM, 1970-1972) recounted in the family memoir Subversive Lives (2012) how he and his comrades would be censured for “disturbing classes” as they rallied students, encouraging them to boycott classes as a sign of protest. Quimpo’s brothers were active in the radical movement; one of them would be killed, another deemed desaparecido.

“You can imagine how conflicted the administration must have been at the time,” says Brian Giron, a History Department instructor. “You are threatened with closure, if not regulation, if you don’t abide by the policies of Marcos.” Closure would render the university unable to facilitate any form of discourse. It would have to kick out some students, including Begg, Celestial and Nathan Quimpo.

Life below ground

On display in the Bantayog Museum is the last uncensored issue of the Manila Chronicle, dated September 22, 1972. Beside it is the next morning’s Sunday Express front page, headlined: “FM DECLARES MARTIAL LAW.”

Quimpo says that the declaration quieted demonstrations for a time, as policemen showed up at rallies ready to arrest students. Student involvement “was almost like a club” before the declaration, he recalls. “But with Martial Law, it got serious,” he says in a mix of English and Filipino. “Students were no longer just going to be members of [KM]. They were going to be members of NPA and the Communist Party, with definite jobs to do to fight the regime.”

Arceo, Silva and Begg all joined the New People’s Army (NPA). Ateneans who had already graduated by the time Martial Law was declared, like Manuel “Sonny” Hizon Jr. (AB EC-H ‘72), Nicolas “Nick” Solana Jr. (AB EC ‘69) and Emmanuel “Eman” Lacaba (AB HUM ‘70), also went underground. Hizon and Lacaba were noted student activists, with the latter being a co-writer of the controversial 1968 youth manifesto, “Down from the Hill,” which was published in The GUIDON. Solana was known for his support for farmers and urban poor. Edgar “Edjop” Jopson (BS ME ‘70) was particularly prominent for his leadership. He headed the National Union of Students of the Philippines and later, after a stint in law school, became a leader in the leftist movement. All seven were killed in military encounters in the provinces.

In 1975, Celestial, who had been giving financial and logistical support to the movement, was found dead in the Montalban River. Nobody has been charged with his death to this day. Emmanuel “Manny” Yap (AB EC-H, ’72), who pushed for the radical reformation of Lakasdiwa and later became its chairman, went missing in 1976. His fate remains unknown.

“If you look at these people and their backgrounds, how intelligent they were, how smart they were… how economically viable they would have been, how promising their careers would have been, how talented they were—it leaves a ghost,” says Giron. “When you kill people like that, it leaves a vacuum that people feel cannot be ignored.”

Carrying on

“At least we are around; we can write [about them],” Quimpo says of survivors. “It reminds us… they were not faceless.”

But those who stayed aboveground were not faceless either. Montiel cautions against forgetting those who rendered their service without armed struggle. “There were many other struggles on campus. Not as dramatic, but just as effective and maybe [as] lasting as what these martyrs did,” she says.

In Montiel’s Down from the Hill: Ateneo de Manila in the First Ten Years Under the Martial Law, 1972-1982 (2008), Ma. Elissa Jayme-Lao of the Department of Political Science points out that because of the limitations placed by the Martial Law, “the struggle against the dictatorship could be effectively channeled toward social if not openly political involvement.”

After the Martial Law was declared, the university focused on social involvement; organizations like the Ateneo Catechetical Instruction League and the politically oriented Ateneo Student Catholic Action were revived. Sarilikha, an organization known for emphasizing volunteerism without political agenda, fielded members to assist various underprivileged sectors outside campus. It evolved into the Office for Social Concern and Involvement, which institutionalized the university’s efforts for nonpartisan community involvement.

The Ateneo student council also began to prioritize social commitment after its radical leaders went underground. It focused on the need for awareness through student-sponsored symposiums that called for political involvement. Despite warnings about possible arrests and detentions, council members joined some rallies, although less than in previous years.

“If you look at it, the other side of Atenistas who didn’t necessarily just fight outwardly, were also fighting demons as bad as Marcos,” says Giron. “At the end of the day, social injustice is just as bad as a tyrant. Poverty is just as monstrous and as scary and as enslaving as a tyrant.”

Down from the hill

Giron adds that these villains are still prevalent. “I think that the need for Ateneans to make an intervention is still as important, as urgent, and as imperative [today],” he says. “It’s for us to go out there and to be among Filipinos. To mix in, to blend in, to be among them, to be no better, to be no worse, to just be a common Filipino who sweats, who toils, who cries, and shares the experience with other Filipinos.” Montiel likewise calls on the youth to be more sincere, to think less about how involvement will help their careers and more on how it will help others.

“I don’t think the picture of Imelda did harm as much as the harm we do our name every day when we don’t act like proper people,” Giron explains. “For every good name, I can name you a politician out there doing bad things who will have a diploma from this place.” His viral blog entry, “The Other Ateneo,” was posted after an uproar on social media over former First Lady Imelda Marcos’ visit to the Ateneo at a scholars’ event last July. Giron’s piece characterized two Ateneos: The ground for service-oriented critical thinkers, and its evil twin, the elite, privileged and socially detached brand.

Giron adds that the former Ateneo still exists; it was in the students who spoke out about the Imelda incident. “It’s not faculty members who make things go viral. It’s the students—it’s the younger generation… The fact that there was outrage is confirmation for me, was affirmation for me, that we teach our kids right.”

Quimpo adds that technology today has allowed the youth to be more aware about current events. “A lot of what is happening is actually translated into pressure on your generation,” he says, citing issues on employment and environment. “So I wouldn’t want to think that you have to worry about the same things that we had before. But at least it should direct you… ‘What do I get involved with?’ For us, it was activism and political activism. [With you]… you have to define that. But certainly, it’s no easier for you than it was for us.”

We pass the Wall of Remembrance once more on our way out of Bantayog. Giron reminds us that the martyrs’ Atenean identity is not written on the wall—here, they are recognized as human, not as Atenean. “I think what these people, these 11 [martyrs], did, was precisely to shed Atenista as a name and just become Filipino.”

We walk out the gate to Quezon Avenue. To the left is EDSA, where two million gathered almost thirty years ago to oust the dictatorship. Behind and above us towers the Inang Bayan.

Updated: 10:51 PM, Sept. 17, 2014