Depression gets a pretty bad rap. We’re taught that feeling terrible must be rooted in a definite cause, like guilt, or an abusive family or a life-changing trauma. So when a friend decides to open him or herself up and say that life seems pointless, it’s brushed off as a mood, something that can be gotten over.

In his July 2013 column “Road to nowhere,” Apa Agbayani wrote for The GUIDON about his experience with depression and how difficult it can be to explain it to others. He states that when it comes to treating depression, “seeking psychiatric help and medication are almost considered bourgeois cop-outs.” One anonymous user commented “O, the travails of being Atenean.”

A widespread attitude like this makes for an environment that wrongfully views asking for help as weakness. Those suffering from depression find it difficult to open up to friends or family, or don’t know where to find professional help. As a result, cases of depression often can unnoticed, undiagnosed and untreated.

It becomes an urgent matter, then, to gauge how serious and widespread depression is in the Ateneo. In light of that, there must also be a reassessment of the measures the administration has taken in addressing this problem.

Official measures

Some people have a hard time believing that depression even exists. But for Albert Go, a clinical psychologist and a staff member of the Office of Guidance and Counseling, “It can’t be denied.”

“In terms of the reasons of referral for our students, it really does consist mainly of depression or anxiety experienced by students for a variety of reasons,” says Dr. Peter Gatmaitan, Director of the Guidance Office. “These reasons could include, but would not be limited to, family problems, academic concerns, relationship problems, and the like.”

According to Bernadette Go, part-time lecturer of the Psychology Department and mental health specialist, sometimes there are tell-tale signs that indicate whether a student is going through depression. According to her, some of these indicators are when a student constantly skips classes, submits work late or doesn’t submit work at all.

The Guidance Office tackles the problem of depression and other mental disorders by way of three committees. The first deals with screening, the second deals with intervention and the third deals with prevention.

Gatmaitan hopes that by the next academic year, a screening process specifically designed to detect cases of mental disorders will be put into place. Hopefully, “all 8,350 students will be screened, will answer questionnaires that will target concerns related to depression or anxiety and suicide.” This is to ensure that the Guidance Office reaches out to students in distress more efficiently.

In terms of intervention, the measures involve collaborating with other offices such as the Associate Dean of Academic Affairs (ADAA), the Associate Dean of Student Affairs (ADSA) and the Office of Health Services (OHS) by way of referral.

Collaborating with all these offices speeds up the process. Gatmaitan says, “Any referral we receive in a day is typically endorsed to a team member [on the] same day. Before, there was a delay in actually receiving the case and assigning the case to a counselor or therapist.”

By way of prevention, again, the Guidance Office turns to the power of teams. “We’re going to have a total of at least around 18 different groups—think group therapy—that would be for prevention.” He elaborates that these groups will take care of addressing different student groups and their various concerns.

As of press time, however, the new screening process has yet to be proposed to the Vice President of the Loyola Schools. “We’re going to make a final pitch to them, to the Vice President, some time first week of March. The ADSA’s office is already aware, many offices are already aware, we do intend to change the screening process for students.”

Young blood

Of course, every experience of depression is different. It varies greatly how students recognize that there might be something wrong with their mental health, as there are many ways by which depression can be dealt with.

For Bea*, signs were very vague at first. “At first I thought it was a sleeping problem.” Then the Guidance Office asked her to come back after she was tested positive as a likely candidate for mental illness.

“I myself didn’t know why I was depressed,” she says, which made it more difficult for her to admit to her parents that she felt something was wrong. “They were trying to force me to give me a reason,” she says. “They kept on saying, ‘May pera tayo naman, nag-aaral ka sa magandang eskuwelahan, you have support naman from your friends, bakit ka depressed?’ (We have money, you study in a nice school, you have support from your friends, so why are you depressed?) And whenever I’d tell them ‘I don’t know,’ they’d get mad.”

For Amanda*, it happened in high school. Hers was a case of not knowing what exactly caused the depression, but suddenly noticing that it was there and that it couldn’t be easily gotten rid of. “I felt like there was something I couldn’t shake, even fun things didn’t make me happy. So I had to really kind of think about it and really read about it.”

After a problem was identified, Amanda approached her school psychologist for counseling. “I got more insight [because of therapy]. I felt like I wasn’t ready for medication. Talking about it made me realize just how big of a problem it was. Usually it stays inside and it festers but I think it helped and I got to hear myself talk about what was causing it, and like how to approach everything from there.”

Sarah* describes when she first felt depression as “a sudden loss of interest in what I felt kept me going.” She continues, “I figured the feeling of helplessness would go away, that it was a natural adolescent phase, but it didn’t, even if I kept myself busy.”

Because of her depression, she resorted to slashing herself. It was her self-harm habit that alerted her parents to her situation. She initially feared her parents would punish her because of her scars. “A few months ago when my mom found me crying on my bed, she shouted, ‘Akala ko ba lalabanan mo yang depression na ‘yan?” Depression lang ‘yan (I thought you were fighting that depression. It’s just depression.)’ as if the pain wasn’t real, as if I’d only been craving for attention all this time.”

Eventually Sarah was sent to a psychiatrist and was prescribed medication. “I just took my meds regularly, and in the state of calmness, I’d think about the reasons behind the mental illness. I was pretty aware that my depression was caused largely by the pressure of making myself look beautiful, physically.”

The ways in which young adults deal with depression often yield mixed results. Some come to an understanding of why such a feeling had come about, others are left still not knowing where their sadness came from.

Local mentality

In terms of local culture, Filipinos tend to attach a sense of apprehension to mental illness and seeking professional help. For Gatmaitan, the stigma can be found in our language.

“We have specific terms in Tagalog and English that refer to this. In Tagalog, it’s more colorful, because the questions asked are typically, ‘May sayad ba ako? May topak ba ako?’ In English, the questions that are usually of concern in relation to stigma are, ‘Am I crazy? Am I effed up?’”

“People are not comfortable talking about it, saying they’re seeing a psychologist or seeing a therapist,” Bernadette Go says. “Psychology as a field in the Philippines is just starting. It’s not as developed or established as in the Western region,” she says in a mix of English and Filipino.

She continues, “The Philippines by nature is very collectivist. It’s intergroup-oriented rather than individualistic.” Because Filipinos tend to be very concerned of what people think of them, it takes a lot of courage for them to come out and admit they might have a psychological problem.

Gatmaitan shares the same sentiments, noting that the stigma can also be connected to our non-confrontational culture. “In terms of depression, there is this concern that if I ask for help here in the Guidance Office or anywhere else, I will be judged. That’s the specific word that’s been used by students.”

Healing

So what does it take to create an culture of openness? Is it possible to cultivate an environment where people don’t have to fear being judged for admitting to their problems or seeking professional help?

For Bernadette Go, education is one of the best ways to correct misconceptions about mental illness. “Sometimes it’s like that. When you talk about mental illness, that equates you to being crazy, being irrational.”

She adds, “Depression really has biological origins. For some, it’s not something that’s always there. For Bernadette Go, education means letting people know that depression is real and not just a trend or a phase.

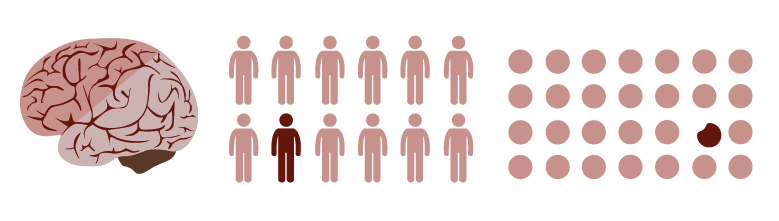

Gatmaitan suggests that education also means looking at the bigger picture. “Stigma, I believe, stems from not understanding [depression] in its entire context.” According to Gatmaitan, 13 to 17 percent of a nation’s population experiences mental health concerns. “That has been pretty consistent in different countries,” Gatmaitan states. “If we know that, we dispel certain myths such as that it’s a middle class problem.”

Albert Go acknowledges that students have a tendency to turn to their friends before seeking professional help. “We acknowledge that students would go to their friends than us. But if it gets more serious, bring them to us.”

When it comes to engaging those going through depression, Gatmaitan offers that the best thing to do isn’t to propose solutions right away, or just ask them to be happy. “They want to feel understood first.”

“We need a support system,” Sarah believes. “Know how a group of people who can understand will definitely keep you going. I can say that with 100 percent assurance because, well, I’m still alive.”

* Editor’s note: The names of these interviewees have been changed to protect their identities.