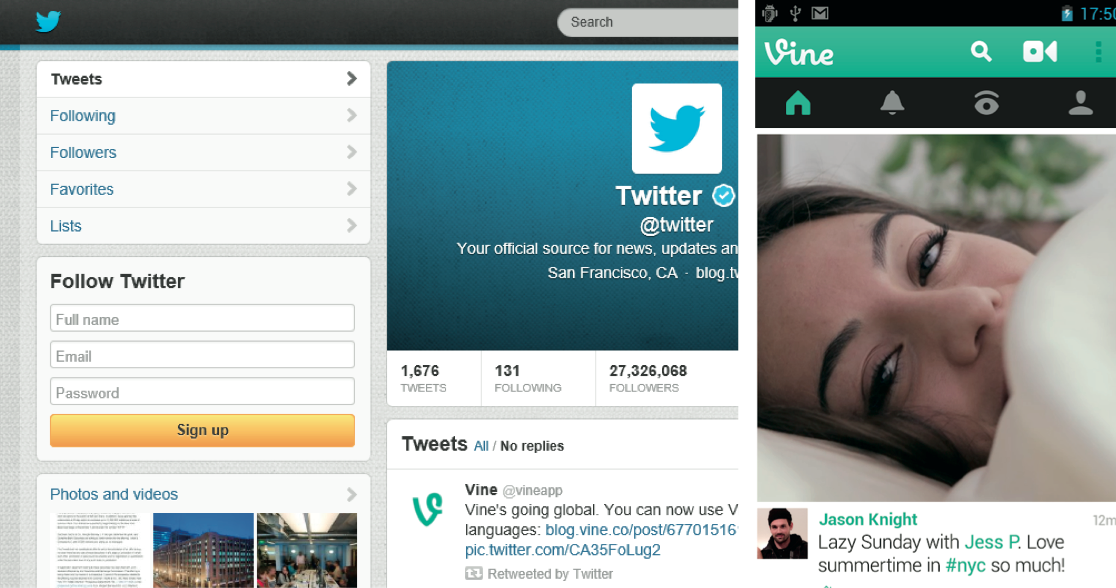

The Twitters, Vines and BuzzFeeds of the world have invaded our screens. Short form media, a phrase that typically referred to short ads, billboards and coupons, now refers to 140-character compositions and six-second videos.

For communication sophomore Paolo Fajardo, the popularity of short form nowadays is closely linked to the speeding up of modern-day lifestyles. “A rising action and a climax have been given a denouement from two minutes to six seconds,” he says. “The need for accessible, on-the-dot entertainment has never been greater.”

But short form nowadays provides more than just entertainment. It is also giving way to a new means of expression: Bite-sized art.

The long and the short of it

While one would think that distinguishing between long and short form media is easy, the lines between the two can sometimes blur. In the advertising world, for instance, a one-minute commercial can be considered rather long.

Differentiating based on content, then, might be a less subjective way of determining what is and isn’t short form. Advertisements that go into detail about a particular product or service are considered long and those that don’t are considered short.

But short form has found its place outside the realm of advertising as well. Flash fiction—a kind of literary work usually around 300 words long—for example, has been slipping into the Twitterverse through what netizens refer to as twitter fiction, or “twitfic.”

One of the earliest versions of Twitfic started out as 140-character summaries of famous novels. In Alex Aciman and Emmett Rensin’s book Twitterature (2009), classics are retold—in the loosest sense of the word—in a series of tweets. (The one on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: “I often think of the craziest thing I could get away with using my MD.”)

Famous British authors also got to try their hand at short form when they were challenged by The Guardian to write 140-character “novels.” “The summer night was heady with the scent of lilac,” reads period fiction author Philippa Gregory’s entry. “He heard the click of the garden gate; and saw a glimmer of her dress as she left.”

Similarly, WriterSkill, the home organization for creative writing majors in the Ateneo, started its annual TweetFic project last year. The project allows members and non-members of the org to participate in the online contest that involves tweeting original fiction stories for a chance to win prizes.

WriterSkill President AJ Elicaño says that the contest is a means of connecting long form with the short. “It’s a way of making writing and literature more accessible and of sharing what we do as writers with the greater community.”

The artistry

However, the claim that art has been made more accessible though short form media is still a contentious one. Its style still leaves some doubting the medium’s merits as genuine artform.

“Art will always be subjective to the contexts,” says English Department Instructor Daniel Olivan. “So what was art before may not be art now and what is art now may not be art in the future.”

Olivan isn’t labelling short form media as art just yet. But he isn’t counting it out either, saying that there is a “possibility for art” in the medium.

Vine is one such platform that has been tapping short form’s potential for artistry. Although more popular for comedy sketches, the app has gotten people’s creative juices flowing. For example, Jethro Ames, a well-known Viner, makes use of everyday objects, from kitchenware to toy cars, to create six-second moving picture masterpieces. Earlier this year, he won the Tribeca Film Fest #6SECFILMS Vine competition for his stop-motion video “How to Clear your Garage From a Scary Ghost.”

A number of other Viners have gone the same way. Khoa Phan was deemed Vine’s Most Creative Stop-Motion Animator by Mashable. Phan brings “papermen” to life through creative pieces like “I just want to be perfect,” in which a ballerina cutout performs for the audience, and “The Paperman’s escape,” featuring a paperman trying to get away from his creator.

It’s a possibility, then, that the constraints imposed by short form social media actually challenge their users to be more creative. Ames, for one, prefers Vine’s six-second cut-off over Instagram’s 15 seconds.

“The six-second format pushes the creative limits in a way that 15 seconds doesn’t. The community for video watching is a lot stronger on Vine—they’re supportive and more engaging,” Ames explained in an interview on the website Digiday.

This hasn’t stopped a community of artists from emerging on Instagram, though. Artists Olek and Shepard Fairey are two Instagram users who take full advantage of its video platform. Olek, a Polish-born artist residing in the US, posts colorful pictures and videos of objects crafted from yarn. Fairey, on the other hand, shares edgy clips of street art in progress.

“I think we’ve reached the limit of shortening. Six seconds is pretty fast,” Fajardo predicts. With that kind of time constraint, the potential of the medium is heavily reliant on the work’s quality itself.

Quality over quantity

For Olivan, the progression from blogs to Twitter and YouTube to Vine is representative of the culture of the millennial generation. Because we’ve grown up with the instant gratification of sendign and receiving information pretty much instantaneously, we tend to think in short bursts, resulting in 140-character and six-second ideas.

But Olivan maintains that there is a lack of scrutiny when it comes to short form as an art. A quick video of a cat twerking to Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball” for example, hardly compels us to think about the “vicissitudes of life.” He explains, “There is a time for a deeper discourse on what you’re seeing. That involves critical thinking.”

However, one can’t deny that social media sites have become sources of intellectual insight and views as well. In an article in New York magazine, Kathryn Schulz admits that the people she follows on Twitter “function as by far the best news source [she’s] ever used: More panoptic, more in-depth, more likely to teach [her] something, much more timely [and] cumulatively more self-correcting and sophisticated.”

Meanwhile, short and long form media haven’t completely moved away from their advertising roots: In Septmeber 2013, Dunkin’ Donuts launched the first television ad on Vine. Aired during ESPN’s Monday Night Football Coverage, the video featured Dunkin Donuts’ signature hot and iced coffees as players and referees.

Regardless of length and quality, it is clear that both long and short form media will continue to have a place in our lives—the dominance of one does not necessarily dictate the end of the other. As each medium is challenged to surpass its potential, we can only sit back and watch out for what’s to come.