The 7.2 magnitude earthquake that hit Central Visayas on October 15, 2013 has awakened not only the region, but the whole country to the importance of heritage preservation.

In an article by Rappler, the Heritage Conservation Society pointed out no less than 10 churches that were damaged during the quake. Among them were Cebu’s Basilica Minore del Santo Niño, the oldest Roman Catholic church in the country, and Bohol’s Church of San Pedro Apostol, the second oldest in the province.

All over the Philippines, churches are preserved for the benefit of tourism, history and culture. They serve as both public structures and heritage assets. As such, the destruction caused by the quake has revealed the flaws, strengths and the possibilities of Philippine heritage preservation.

Tourism as a moneymaker

Many old structures across the country serve as tourist attractions in their respective localities. This was the case in Bohol prior to the earthquake.

“Its economy had developed very well—there are lots of people who go [there] for the tourist attractions and part of these are the churches,” says Dr. Victor Venida of the Economics Department. “The churches are part of the [tourism] package.”

While this bodes well for the tourism sector, the preservation of these heritage assets entails costly funding. A lot of money is needed to acquire needed materials and services that are not easily found in the Philippines or in the present, such as the coral stones used centuries ago.

While churches are provided for by collections during Mass and donations from organizations, taxes from tourists are also given to the establishments for their maintenance and upkeep by the government.

However, Mr. Jody Navarra of the Butuan Global Forum (BGF), a non-government organization that advocates heritage preservation and ecotourism, is against seeking financial support from the government. “We avoid any involvement with them because we [believe] that the private sector of Butuan can pretty much go on its own.”

He finds fault with the tourism council, saying that their funding only puts historians under pressure to find history ready for tourist consumption. “They are using tourism to justify [government] projects, [and they only] talk about how we can develop tourism using history,” he points out.

“Butuan… should have its own historical and cultural commission independent of tourism, so that it will have its own objective search for the truth,” he says.

Keeping the past alive

Despite the importance of preserving the country’s cultural heritage, however, there are still quite a number of hindrances.

One of these is the increasing demand for real estate in Metro Manila. Land developers are building more high-rises in residential areas, entailing the demolition of many long-standing structures.

The case is different in places far from Metro Manila, such as Vigan, Ilocos Sur. Venida commends Vigan City for maintaining its old structures, attributing this in part to the city being relatively far from big commercial areas.

“You see, [these structures] can survive if they’re away from the main cities. That’s why in Manila we have a problem preserving our old buildings—they’re located in places where there’s a very attractive real estate opportunity to be made,” he says.

Buildings are not the only pieces of cultural heritage that ought to be preserved. One of BGF’s projects tries to maintain its heritage through “Balangay Masawa Hong Butuan” by taking a traditional balangay on a voyage around the Philippines and Southeast Asia to let people experience the historical vessel firsthand.

Even intangible heritage such as language ought to be preserved. In an article published by The Philippine Star, Department of Education Secretary Br. Armin Luistro, FSC, reported that there are more than 170 languages in the country. Four of these have become extinct while 24 are on the brink of the same fate.

“A language, in order to survive, has to be spoken,” Navarra says. He believes that language is what binds ethno-linguistic people, making many of their interests mutual in nature. “If the language is lost, our identity is lost.”

Economics of preservation

Venida asserts that while restoration is a difficult task, it is indeed possible. “It’s just a question of will,” he says. “We’re talking about young people who would be willing to spend the next 20 to 30 years of [their] lives making sure these [structures] get restored and at the same time saving and preserving them properly.”

He also says there is a lack of workers trained in the sort of craftsmanship needed to maintain or restore old structures. Nonetheless, he points out that the training can be done and that restoration is a means to create more employment opportunities.

While these measures are feasible, Venida says that there is another issue: Returns. “By the time you’d have spent so much on restoring [these structures], what are you expecting in return?” he asks. “It’s like a business: If you’re going to invest so much in building a factory or a mall, you’re going to have to earn a profit.”

He refers to these factors—the costs, expectations and returns—as the “economics of preservation.” Restoration involves not only the final product, but also what goes into the rehabilitation and what will happen to the structure once it’s been restored.

Sense of urgency needed

Venida hopes that the tragedy that struck Bohol and Cebu will serve as a catalyst for better preservation of the country’s existing structures.

Efforts to properly care for and maintain our heritage must be increased so as to preserve it for future generations. “Something must be done as early as possible,” Venida says. While the fallen churches may still be restored, our still-existing heritage sites are also in need of a “sense of urgency” from the Filipino public.

Navarra asserts that heritage preservation is a shared responsibility between the private and government sectors. With determination and commitment, the task may not be impossible.

National treasures

Sources: whc.unesco.org, cnngo.com

The Philippines is the proud home of a total of five United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) World Heritage Sites. The GUIDON takes a look at these sites and whether or not they have been preserved well over the years.

1. Vigan City, Ilocos Sur

Taking a stroll through the streets of Vigan is like being transported to an entirely different world—a communion between daunting yet beautiful Spanish architecture and modern-day technology. Established in the 16th century and officially inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1999, Vigan has earned its reputation as a historical marvel, attracting tourists from all over.

Preservation Status: Very well preserved and recognized as one of the best-managed heritage sites in the world.

2. Rice Terraces, Cordilleras

Popularly regarded as one of mankind’s most harmonious co-creations with nature, these Rice Terraces are considered by the Unesco World Heritage Center as “a living cultural landscape of unparalleled beauty.” What separates this pinnacle of Ifugao cultural heritage from other rice terraces around Asia is that it was built at higher altitudes and steeper slopes for a unique rice strain that germinates in cold weather. It earned its official inscription as a World Heritage site in 1995.

Preservation Status: It was once on Unesco’s Danger List, but has since been removed. It is now undergoing more long-term preservation measures.

3. Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park, Palawan

Measuring 8.2 kilometers in length and generously decorated with stalagmites and stalactites, this underground river is truly one-of-a-kind. Flourishing with flora and fauna, it serves as a diverse ecosystem valued by sightseeing tourists and scientists alike. It was given its official inscription as a World Heritage Site in 1999.

Preservation Status: The river has been effectively preserved thanks to the efforts of environmental advocates, such as former Puerto Princesa Mayor Edward Hagedorn. However, it must be noted that the influx of tourists may pose a threat to the river’s conservation.

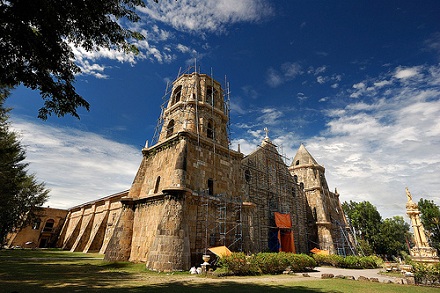

4. Baroque Churches

Unesco recognizes four Baroque Churches as World Heritage Sites: Nuestra Señora Church (Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur), Immaculate Conception Church (Intramuros, Manila), San Agustin Church (Paoay, Ilocos Norte) and Santo Tomas Church (Miag-ao, Iloilo). Each constructed between the 16th and 18th centuries, their architecture is an interpretation of European Baroque by the Filipinos and Chinese. They were officially inscribed as official World Heritage Sites in 1993.

Preservation Status: Somewhat preserved. While some parts of the churches were added in later years, much of the original materials and features were retained.

5. Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park

Encompassing 130,028 hectares of space according to Unesco measurements, the Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park is hailed as the eighth best dive spot in the world by CNN Travel. It is also home to around 350 coral species, over half of the world’s total number of coral species. It was officially inscribed in 1993 and was the earliest on the list of Filipino Unesco heritage sites after the Baroque Churches.

Preservation Status: Undergoing rehabilitation since being damaged by a US ship running aground on the reef early this year.