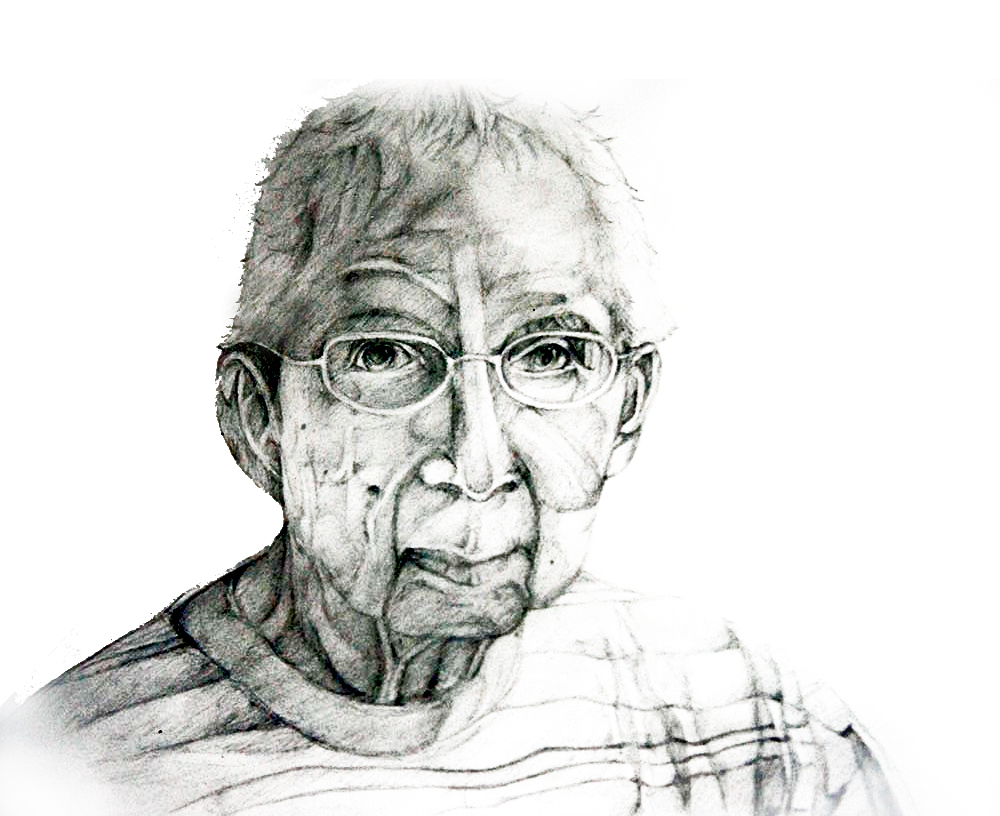

TRUE TO his status as one of the Ateneo’s “legendary” professors, quite a few legends surround the name of Fr. Roque Ferriols, SJ.

Padre Roque, as his students fondly call him, was born on August 16, 1924, on the feast day of St. Roch. He spent his childhood in North Sampaloc, where he was exposed to various languages, including Spanish, Ilocano and Tagalog.

At 16, he entered the Society of Jesus. There he excelled in his studies of Greek and Latin—a skill he continued to use well into his years as an educator.

As was customary for Jesuits in the Philippines, Ferriols went to the United States to study theology and philosophy. After being ordained in 1954, he went on to get his doctorate in philosophy at Fordham University.

Afterwards, along with the late former University President Jose Cruz, SJ, he brought existentialist phenomenology to the Philippines—the brand of philosophy that now characterizes philosophy in the Ateneo.

Ferriols retired in 1984, as is customary of faculty members when they turn 60. However, Ferriols opted to keep teaching part-time.

He earned the Gawad Tanglaw ng Lahi award in 1989 and was named Professor Emeritus in 2006. The title is given to seasoned faculty members who have retired but may retain their status as professors. Though not required to teach, they may still opt to do so.

Then, on on October 22, 2013, after 50 years of service in the Ateneo, 89-year-old Fr. Ferriols decided to stop teaching completely.

Touch of the common

It is a Jesuit tradition to include philosophy in their schools’ core curricula. But before Ferriols and Cruz introduced existential phenomenology to the Ateneo, studying philosophy centered on cosmology, metaphysics and the like.

Philosophy Department Chair Agustin Rodriguez, PhD, a student of Ferriols in the 1980s, explained that existential philosophy is rooted in man’s experiences.

“‘Yung istilo ng pamimilosopiya [na ito], ‘di nagsisimula sa sistema, pero sa buhay na karanasan ng tao (This style of philosophizing does not start with a system, but rather, with the experiences of the human being),” Rodriguez said.

Philosophy Department Associate Professor Leovino Garcia, PhD added that Ferriols’ philosophy had a “touch of the common.”

“Philosophy must be rooted in life, must come from lived experiences,” he said. “Philosophy is not just organizing concepts. It’s about really grappling with living issues.”

Garcia added that Ferriols was able to provide a sense that philosophy could be relevant even to those outside the academe.

Philosophy in Filipino

Ferriols also pioneered philosophizing using the Filipino language. Many mistakenly believe that he is the Father of Filipino philosophy, but Rodriguez said that this is not quite the case.

“He was the first to reflect not on philosophizing about the Filipino, but in Filipino,” Rodriguez clarified.

Garcia added that Ferriols never labeled his philosophy as “Filipino philosophy.”

Philosophizing in Filipino eventually led to teaching in Filipino, for which the Ateneo Philosophy Department is now known. Garcia said this is Ferriols’ biggest contribution to philosophy.

Ferriols, the philosopher

The late historian and former Jesuit Provincial Fr. Horacio De La Costa, SJ once said that Ferriols might be the only real genius in the Philippine Province of the Society of Jesus.

He is known to be fluent not only in Filipino and English, but also Greek, Latin, Spanish, French and German. He read Martin Heidegger’s works in German, translated the writings of French philosopher Gabriel Marcel to Filipino and he can quote parts of the Iliad in Greek and translate them into English. He can also speak in different local languages.

Rodriguez said that, though he and his fellow faculty studied, taught and perhaps wrote more about philosophy than Ferriols, no one matches Ferriols’ way of thinking.

“Parang siya lang talaga sa department na ‘to ang puwedeng tawaging philosopher (It seems like he’s the only one in the Philosophy Department who can truly be called a philosopher),” Rodriguez said.

However, Ferriols is also regarded as a man marked by simplicity and humility. “[Whenever he talked,] it was never about [himself]; it was always about the truth,” Rodriguez said.

Garcia, who first met Ferriols in 1962 and has been his friend for more than 50 years, thinks of Ferriols as someone “remarkable.”

“For many people, Ferriols is…like an institution—a symbol, an icon,” he said. “[But] he’s down-to-earth.”

Teacher and friend

Legendary status aside, Ferriols is very much a reglar person: He wears slippers, likes chocolate, and in his younger days, had run alongside a bus in his soutane.

When asked to recall fond memories with the Jesuit, former students often talk of their encounters with Ferriols beyond the classroom.

Philosophy senior Nicole Tosoc recalled an instance when she and some friends had gone to give Ferriols chocolate. “I said, ‘Padre, you like chocolates, right?’ He said, ‘My only sin is chocolate.’”

Although Tosoc described Ferriols as “very benevolent,” she also shared that Ferriols would get angry in class whenever a student failed to answer questions properly.

Garcia added that Ferriols used to be feared by students. “If you didn’t study, he would really berate you,” he said. But Ferriols was not simply a teacher who was quick to anger.

According to Rodriguez, “Pag naninigaw siya, hindi siya naninigaw dahil lang uminit ulo niya… Laging witty ‘yung pagsigaw niya sa mga estudyante (When he shouts at students, it’s not out of blind rage. He doesn’t just spout angry words, he’s always witty).”

His biting wit aside, Ferriols was also quite determined to help deserving students.

In his article entitled, “Meron Philosopher: Fr. Roque J. Ferriols, SJ,” Garcia wrote of Ferriols:

“He fired my imagination, gifted me with the passion for philosophy, and inspired me to dedicate my life to philosophy. Like Morrie in ‘Tuesdays with Morrie,’ he saw me as a ‘raw but precious thing, a jewel that with wisdom, could be polished to a proud shine.’ He believed in me and continues to believe in me.”

Self-reflexivity

Though he has decided to stop teaching formally, his ideas and philosophy continue to engage students through the generations of his former students who are now part of the Philosophy Department.

“[Ferriols] has taught nearly all of us,” Garcia said. “That’s how philosophy is, there is a generational development, which is the strength of the department. The older people prepare the younger people.”

But perhaps it because they were his pupils that the faculty members were saddened by his retirement. “In our minds, it would be good to still have him around because he’s an inspiration to students,” Rodriguez said of the department’s reaction to the news.

But Garcia added that overpowering that sadness is a great feeling of admiration for Ferriols’ decision. “I think that’s remarkable, for an old person to have a self-reflexivity. The ability to see that you can no longer do it, and to have the courage to admit it,” he said.

Although he developed Parkinson’s disease around seven years ago, Ferriols chose to continue teaching “for as long as he could.” Over the years, his classes have greatly diminished in size.

His last Philosophy 101 class last semester had only 16 students, while the average class size is 40. It was also held in the JM Lucas Infirmary.

Rodriguez added, “He realized he wasn’t as effective as he could be, and he doesn’t want to teach if he’s not going to be as effective as he can be.”

Though he no longer teaches philosophy, Padre Roque will always be remembered as the fiery, “angry, young Jesuit” who would berate unprepared students. But more importantly, his wisdom and contributions to the field of philosophy will continue to inspire fellow philosophers and Atenean students long after his retirement.