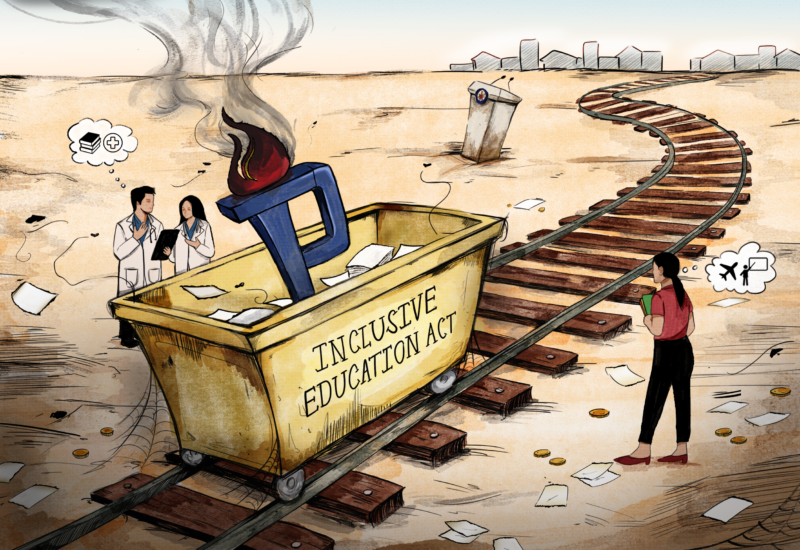

Voting 14-0, the Supreme Court (SC) declared the controversial Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) unconstitutional on November 19. The High Tribunal also declared the use of the Malampaya Fund and the President’s Social Fund (PSF) illegal beyond their mandated purposes. The remaining allocations in the 2013 PDAF, together with the abolished portions of the Malampaya Fund and the PSF, will be returned to the national treasury.

As of press time, a proposal has been made to repurpose the unspent PDAF, as well as the 2014 PDAF, to a supplemental budget to boost relief and rehabilitation efforts in calamity-hit areas of the country.

The SC ruling was met with largely positive responses from Filipinos, with many lauding the SC for making a step towards transparency and good governance. Stripped of their power to intervene in the execution of projects after the budget approval, legislators can no longer abuse their pork at the taxpayers’ expense. Congressmen and senators will become what voters expected them to be–makers of law, not money.

The ruling will strengthen the ill-defined Philippine government institutions. The executive and the legislative branches are now expected to ensure that each item proposed in the budget complements the administration’s national development plan.

The decision marks another triumph in the fight against corruption. However, the abolished funds provided for the welfare of the Filipinos too; the PDAF, in particular, has funded several projects that benefitted many individuals and communities, the fates of whom are now left uncertain.

With the PDAF abolished, some local officials will need to seek alternative funding for the establishment of elementary schools and barangay halls, as well as for the repair of typhoon-damaged classrooms. A PDAF-funded project for an elementary school in Barangay Langgawisan in Maragusan, Compostella Valley, where many residents belong to the Mansaka tribe, is now in danger of being left unfinished.

Soft projects, which include hospitalization and scholarships, will need alternative sources of funding as well. Though the Commission on Higher Education has promised to look for other sources to subsidize the thousands of scholars that the PDAF has supported, it is unclear where these funds will come from.

In the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, the PDAF was being utilized to develop peace-building projects, including roads that interconnect poor rebel territories to trade areas and town centers. Now, they also face the risk of being left uncompleted.

The decision of the High Court to abolish the PDAF as well as parts of the Malampaya Fund and the PSF merits praise. However, it cannot be denied that it also has far-reaching negative consequences. Moreover, the public has yet to be informed about where the money will go.

We can only hope that this will be more than a one-shot victory.