The Ateneo’s admission system has always been regarded with skepticism.

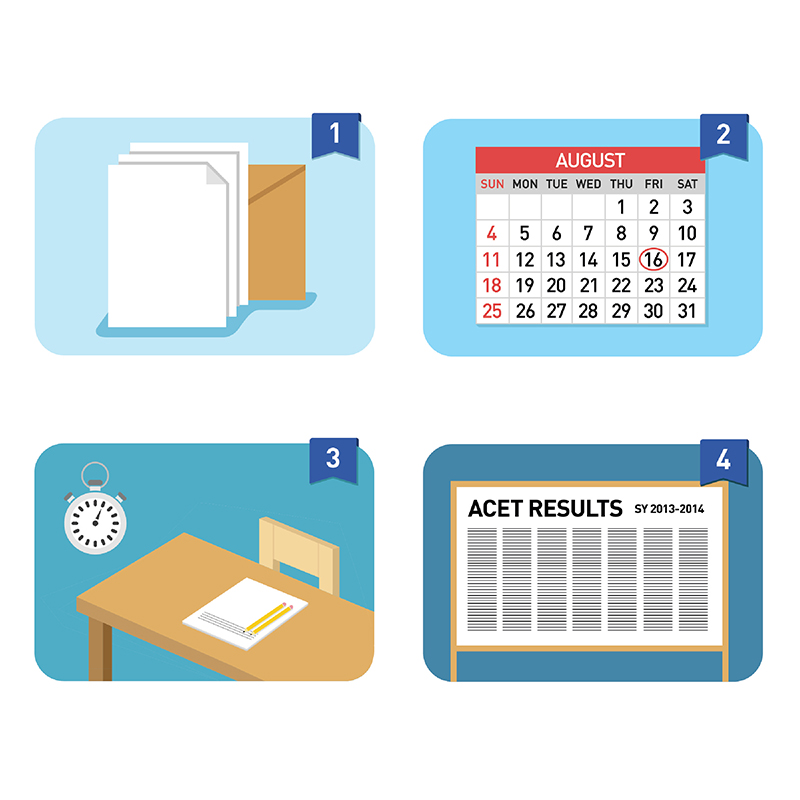

The general criteria for acceptance into the university seem simple enough: Score as high as you can in the Ateneo College Entrance Test (ACET), write an appeal if you’re waitlisted. Academic performance is always the main concern, but if you study hard, the odds will lean in your favor.

In a university whose students are stereotyped as privileged, it’s not difficult to believe that these privileges might have been abused to claim a slot in the Ateneo community. It could very well be that other factors besides academic performance come into play: What high school you came from, how much money you have and who you can get to endorse your appeal are variables that can decide whether or not you will be welcomed into the Ateneo as a student.

There will always be rumors of “palakad cases.” Whether they hold any truth or not is still subject to question. One would be hard-pressed to find students willing to admit that they became Ateneans by buying their way in or by using the political power of their family names. If only out of pride, most Ateneans, if not all, will go so far as to say they’re here because they deserve to be here.

Granted, a system’s deficiencies cannot be proven by mere hearsay. That rumors of such cases remain rampant, however, means that the admission process should be subject to investigation.

Origins of controversy

The Office of Admission and Aid (OAA) is no stranger to dispute. The admission process has always been surrounded by rumors questioning its legitimacy.

For example, some criticize the ACET as being more difficult than most entrance exams. However, in a 1997 article from The GUIDON entitled “72% freshmen score poorly on English ACET,” writer Gino Riola interviewed Dr. Ma. Assunta Cuyegkeng, the Acting Dean of what was then called the College of Arts and Sciences. Paraphrasing Cuyegkeng, Riola wrote: “The low ACET scores are a greater reflection of the quality of primary and secondary Philippine education rather than that of the Ateneo.”

In the article, Cuyegkeng also counter-argued the notion of “pressure cases,” which allegedly displace students who are supposedly more deserving of admission. She explained that “these cases are reviewed after all those accepted have confirmed their entry and after the appeals of waitlisted students have been considered.”

In 2010, Maria Katrina M. Tioseco investigated the existence of a palakad system in another article for The GUIDON entitled “Second chances.” In the article, former University President Dr. Bienvendio Nebres stated in a letter to The GUIDON that, besides academic performance, “there are other values to be taken into account in special cases.” He admitted, for instance, that “the most important group that we spend on are children of the Ateneo de Manila faculty and staff.”

Deficiencies

Jumela Sarmiento, the Director of the OAA, elaborates on the dynamics of the application process.

A committee composed of faculty members from each of the four Loyola Schools bases their decisions on certain factors. These factors are the applicant’s ACET score, high school grades, recommendation letters from teachers, co-curricular activities and his or her personal essay.

Despite how secure and thorough the admission process seems to be, Sarmiento also expressed the difficulties she encounters when admitting students. “Because of the perennially increasing number of applicants, the application process admittedly gets more and more competitive each year,” she says.

Most students who enter the Loyola Schools are the ones who make it to the top 20% of ACET scorers. Those who fall below the cut-off mark (usually limited to the next 20%) are not immediately rejected and have the chance to appeal by writing letters. Waitlisted applicants are required to submit appeals to notify the school that they are still interested in enrolling.

Sarmiento says that the OAA receives hundreds of appeal letters each year. “After the confirmation of those accepted, open slots are identified and another round of deliberations is done by the committee to decide on appeals.”

Sanggunian President Dan Remo says that the student government participates whenever it can, sitting in the meetings of different school councils and committees.

“With every committee, every school year, they try to create rules to be able to try to ensure the processes remain integral, and that’s what Sanggu does,” Remo says. “We really try our best and we work with our administrative counterparts to be able to really bring fair student representation.”

Joshua*, a former Ateneo student who opted to transfer to a different university due to academics issues, was a waitlisted student. He is the son of a faculty member who also works for a company closely associated with the Ateneo. He states that his family name may have played an important part in ensuring his enrollment; one of his relatives is also a renowned Jesuit and is associated with another Atenean university in a different region.

“I wrote my own [appeal] and my grandmother and parents wrote [recommendations],” he said.

When asked if his affiliation with certain contacts in the school meant that he had enrolled fairly, he responded, “I don’t think so. I’m not sure. I’m not allowed to mention who [it was that] endorsed.”

This brings up the question of whether or not these peculiar cases take away the slots of students who enroll without the benefit of being endorsed by esteemed figures. Sarmiento, however, assures that this is not the case. “No students are displaced. The cases are reviewed only after the confirmation of those accepted is done.”

Rumors

There are many ways by which certain students allegedly work around the steps of admission. It’s no doubt that these stories, whether fictional or factual, gain a significant amount of traction.

However, do all these rumors and accusations hold weight or can they be immediately dismissed as mere noise?

Sarmiento notes, “Because of the sheer number of people who want to get into the Ateneo, we understand that admission in the Ateneo will remain to be a controversial topic.”

Remo states that he wouldn’t quite label “palakad cases” as harshly as situations of shady politicking. He says that, while he sees the applicants with probationary status put much effort into get into the Ateneo, that isn’t necessarily suspicious behavior. “They write letters of appeal, they try to get as many contacts as possible, but I wouldn’t so far put it that way [as a palakad case].”

Remo admits that any case of admission will always come with a “buzz of rumor,” believing that some speculations are at times ungrounded. “It’s a habit that I guess has formed throughout the years. Rumor is something not new to this campus.”

However, Joshua says that sometimes there are telltale signs of whether a student made the top 20% of applicants or not. The digits of a student’s ID number can indicate whether he or she was waitlisted; if a student’s middle digits are high enough (meaning they were accepted later than others), then he or she most likely fell somewhere in the ACET’s lower 80%.

Another way rumors of “palakad cases” circulate is when the acquaintances of an applicant find out that he or she is enrolled in the Ateneo, when he or she supposedly didn’t make the cut for the ACET.

As a student who himself has been subject to rumors implying that he was admitted into the Ateneo through connections, Joshua sympathizes with those who become targets of similar hearsay.

“I’ve heard pretty brutal comments from other people about them [students accused of getting in through unfair means] like, ‘They paid the school’ or ‘Oh, it’s because his dad’s rich.’ I’ve heard tons of these. I’d say it’s not fair,” he says in a mix of English and Filipino.

Joshua also believes that students labeled this way are not solely to blame; he says that parents sometimes play a part in instilling the pressure to become an Atenean. Usually, they encourage their children to go to the Ateneo because of factors such as the distance of the campus from their homes and the safety of the location. Such reasons may even prompt parents to discourage their children from applying to other universities.

The benefit of doubt

The admission process is indeed a complex system filled to the brim with nuances, so much so that it can never been seen as unquestionably objective. Even Sarmiento admits, “The academic requirements of the committee are admittedly not absolute and unequivocal.”

However, speculating on the deficiencies of the admission system should not always culminate in accusing other students of exploiting its supposed flaws.

Remo asserts that the student government remains vigilant regarding such cases. “If there are any reports about these kinds of incidences, your Sanggunian would be more than happy to be able to process them and really investigate these things because they matter to students.”

Sarmiento clarifies that her job doesn’t finish with just admitting students into the university. She also closely monitors the academic performance of those who end up being accepted after appealing.

“We have found that a good number not only survive the academic demands of the Ateneo but also finish well. This is because they study very hard and their parents closely monitor their academic performance in college,” she says.

Joshua also believes that how a student initially fares in the Loyola Schools is not necessarily indicative of his or her academic performance in the years to come. He states that some waitlisted students work even harder than those who passed without a hitch because of their probationary status in first year.

“In the end, some of them either shine brighter than the rest or just fail and get kicked out,” states Joshua.

Perhaps the admission process has to step into more subjective territory precisely because of the diversity of its pool of applicants. Though the system’s nuances render it easy for some applicants to breach, there’s a chance of it letting in a handful of late bloomers—those who can prove during their stay that they deserve to be there.

*Editor’s note: Names have been changed to protect the interviewee’s identity.