It’s been three years since the Maguindanao Massacre and there has been no justice.

58 people were killed: Relatives, lawyers and supporters of the Mangudadatus—the Ampatuan’s political enemies—as well as journalists. Andal Ampatuan, Sr. allegedly ordered the massacre to prevent his political rival, Esmael Mangudadatu, from running for governor of Maguindanao in the 2010 elections.

The recent development in the case is the offer of a settlement. This will make the lives of 58 people worth at least 50 million pesos. Besides placing a price on the lives of the victims, the settlement will also require that the victims’ families sign an affidavit to implicate Mangudadatu in the massacre. It is important to note that Mangudadatu lost his wife and other relatives to the murder.

Despite Malacañang’s recent attempt to quell the public’s fear that prosecutors will accept the settlement, the very fact that there is a settlement offer in one of the most infamous cases in recent Philippine history is distressing. It is imperative, however, to examine the reasons of victims’ families for considering a settlement in the first place.

They are facing a stalemate.

It is nothing new to say that the Philippines’ justice system is weak. For example, the trial for the Vizconde massacre of 1991 occurred four years after the murders. The judge’s decision was given nine years after, in 2000. And a full decade later, the Supreme Court acquitted nine of the accused. This was despite previous guilty judgments from the lower court and Court of Appeals.

The government has done nothing concrete to give justice to the victims and their families of the Maguindanao Massacre. Many have already lost faith. What’s worse is that, in the wake of the gruesome murders, the victims’ families did not only lose loved ones; they lost breadwinners, too.

With each passing day of delayed justice, the families are left to deal with meeting their daily sustenance on their own. While it is deplorable that 58 lives were lost in what is allegedly a political attack, the domino effect of the massacre is even more unforgivable.

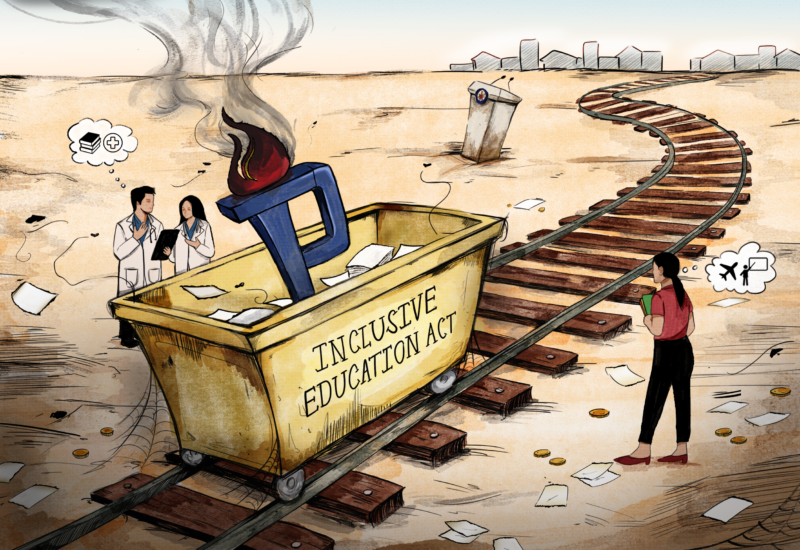

That said, can the families of the victims be blamed if they would rather settle with the Ampatuans than continue scraping by? The issue of settlement is not just about slow investigation proceedings. The victims’ families are in the middle of a chess game played by the forces that have long plagued Philippine society: Poverty and injustice.

The victims’ families are dangling helplessly on invisible strings, with each move either sending them deeper into poverty or further prolonging their wait for justice to be served. And though this is an act that is far from reaching its end, we must question how these families can ever truly win.