A SELF-PORTRAIT. More than anything else, Bluerep’s angst-ridden and high-octane season finale, Spring Awakening, is the story of the people we know best—ourselves. Photos by Alexandra L. Huang.

We’ve all been there.

The world of college can be jarring for those who came from traditional Catholic schools, or who were at least kept under the careful watch of their parents. The change meant being exposed to new things, including, in one way or another, the realm of sexuality.

However, we live in a society that remains heavily influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, which translates into a largely conservative approach to sex.

But Spring Awakening, the season finale of the Ateneo Blue Repertory (Bluerep) this year, wasn’t afraid to go there. Given the work’s risqué themes, staging it in a Catholic university had the potential to be precarious.

Beyond the raciness and the studied defiance of an actor or actress loomed other people’s stories, ones that aren’t always easy to tell. Lean close—the twists may surprise you.

Behind the curtain

Spring Awakening is a rock musical written by Steven Slater with music by Duncan Sheik. It reveals the clash of adolescent sexual awakening with a repressive society in 19th century Germany. Under the wing of conservative institutions, the youth have nothing to prepare them for the changes that come.

This year’s production was directed by Andrei Pamintuan (BFA TA ’08), a Bluerep alum and a Loyola Schools Award for the Arts recipient for theater. Pamintuan previously worked on Spring Awakening in the United States as the assistant director for its first professional production outside Broadway and the national tour.

Coincidentally, the last major staging of Spring Awakening in the Philippines was directed by Pamintuan’s mentor, Chari Arespacochaga. Atlantis Productions presented it at RCBC Plaza, with Joaquin Valdes as Melchior and Kelly Lati as Wendla. Like the original production, it featured onstage nudity.

The two productions are vulnerable to comparison, but Pamintuan aimed to present a take that no one has seen before. “I tell the actors to explore, so we can make Spring Awakening their own story,” he told The GUIDON in an interview a few weeks prior to opening night.

Though the original Broadway version is iconic, the cast and crew of the Bluerep production were advised to forget it completely. “We took it in a very different way with the set, blocking, choreography, lights and sounds. A show that’s an exact replica kind of defeats the whole purpose,” says psychology major Jie Dela Paz, head technical director of the production.

Rethinking an entire production posed an extra challenge. “You have to match the feeling of the lines and the script with the lights and the songs,” says Dela Paz. From the wings to center stage, working on a theatrical production necessitates a fixation for harmony.

Risqué business

However, getting those elements to the stage is another story. The musical involves issues such as premarital sex, abortion, suicide, child molestation and homosexuality, which might not sit well with all people. This brings up the question of where a Catholic institution might draw the line for those staging it.

“[The Office of Student Activities (OSA)’s] concern was in the execution of certain scenes,” says computer science major Nikki Surtida, the production manager. Since the musical was presented on campus, certain conditions had to be met, such as staging it in a less explicit manner.

These restrictions were part of the reason why Bare, Bluerep’s season finale last school year, was staged off-campus. The musical tackled themes like homosexuality, teenage pregnancy and drug use. “They wanted more freedom when it came to the direction of the play. If we staged it [in Ateneo], we’re very bound by the rules,” shares Lara Antonio, a communication junior who payed Martha.

This is not to say the Ateneo acted without proper discretion. “Particular limitations have to be set in place, but not to the point where artistic expression is suppressed,” explains OSA formator Timothy Ong, who handles the Performing Arts Cluster (PAC).

When it comes down to it, dealing with risky subject matter requires balance and respect. “The arts should respect the Church and vice versa,” says communication major Ber Reyes, who played Wendla, the female lead. “All have the right to stand by our own beliefs.”

It’s easy to label risqué art and traditional institutions as opposing forces, but the two can exist in an atmosphere of cooperation. In Spring Awakening, the critical Melchior sings of their education system’s closed-mindedness: “Wars are made, and somehow that is wisdom.” An attitude of acceptance is ultimately what the musical itself fights for.

Pervading issues

Though the play the Broadway musical was based on was written by Frank Wedekind more than a century ago, the fight is far from over. The issues tackled by the play continue to haunt society today.

Those who suffer may be closer to home than we think. Pamintuan says, “Martha in the play was molested by her father. And you don’t know how many people I know na kaklase ko sa Ateneo na mga babae na namolestiya ng magulang nila, na namolestiya ng kuya nila. (And you don’t know how many female classmates of mine from Ateneo were molested by their parents or older brothers.)”

“This is life for some people,” Antonio says of the play. More than just assuming roles, actors possess a responsibility to those who remain unheard. Pamintuan says, “[Spring Awakening] is about everyone, is about someone’s friend, is about someone’s mother or father.” The stage is an arena where human realities are shown.

The play is especially relevant in light of recent events. Last December 21, 2012, President Noynoy Aquino signed the Reproductive Health Bill into law, a move considered as a radical development in our country. The bill faced strong opposition from religious institutions and more conservative Filipinos. Though the Church and State are legally separate, the two have been intertwined in Philippine culture ever since the colonial era.

The law’s passing is a heated issue that necessitates proper dialogue. “Spring Awakening is also about being part of a society that is traditional and how people react to all [of] those changes,” says Pamintuan. Bringing the issues out into the open can stimulate discourse.

This mindset is not lost on the Ateneo. “[Ateneo] is a Catholic university, but it’s a university,” says Glenn Mas, who teaches with the Fine Arts Program. Last year, 160 Atenean professors voiced their support for the bill, inciting the ire of those who insisted that being part of a Catholic university meant adopting the Church’s stance. Complications arise in the face of change, especially when the relevance of tradition is being questioned.

“It’s important to give an uncomfortable view, one that will make them wonder why they’re bothered,” says Mas. When handled wisely, controversy can be a tool to make the audience think about stories that matter.

The dark I know well

The musical deals with dark themes, and this proved to be a baptism of fire for members of the production. “It’s tiring emotionally, mentally and physically,” says Antonio.

Preparation for the Bluerep production was intense. One workshop involved internalizing their personal family dramas. The actors had to scream what they wanted to tell their parents, which proved to be both powerfully cathartic and disarming. “Most of my cast mates ended up crying, and [the emotions] carried over in the run,” shares Tricia Allado, a psychology major who played Thea, a teenage girl who witnesses the dark turn of events in the play.

Working on the production meant facing the fear of being fragile. Actors had to dig deep in order to make the characters real, as if they were undoing their skin to flesh out someone else’s.

The work was particularly heavy for actors who deeply internalized their roles. This was true for management junior Boo Gabunada, who played Moritz, a troubled adolescent who contemplates death by his own hands. Fostering a strong connection to the character made the pain a lot more palpable. “You tend to take parts of that character into yourself, and you put parts of yourself into the character,” he says.

Acting is being brave enough to let a character take over, with the commitment to performance revealing the transcendent aspect of the craft. “Martha—I love her, but she scares me,” says Antonio. As the actors gave life to their characters, they understood that the people they portrayed are undeniably real.

However, it wasn’t always glum. To warm up for one rehearsal, the cast was instructed to run or dance around the area outside Colayco Pavilion while singing a song from the musical. Spirits were high as they belted out lyrics that literally read “Blah blah blah blah” in front of other students, complete with perfect blending and harmony.

After what they’ve gone through together, it makes sense that the cast is tight-knit. During breaks, cast members joked around, reflecting the vibrancy of the childlike teenagers they played. The vigor and closeness of the members of the production provided an effective support system.

Stage whispers

Bluerep’s latest offering had a fiery energy. Working on it required breaking through inhibitions and silences, but that leap resulted in something that marks the true spirit of theater.

Mas says in Filipino, “What theater aims to say as an artwork isn’t in the lines.” The audience must put the story’s subtleties together and, hopefully, be moved.

In a day when too many stories still yearn to be told, it pays to listen. The unspeakable still manages to find body in other forms: melody, nuance, and even flesh.

In its negotiations between risk and tradition, heaviness and light, and tragedy and innocence, Bluerep’s Spring Awakening showed that there is always something to be discovered.

Time after time

Productions in the history of Spring Awakening show just how strongly the work’s issues transcend time and locality.

1. In 1906, Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening: A Children’s Tragedy was first staged in the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. The play caused a stir due to its controversial themes, such as child rape, homosexuality and suicide. This led to further productions of the play being censored and banned until the 1960s.

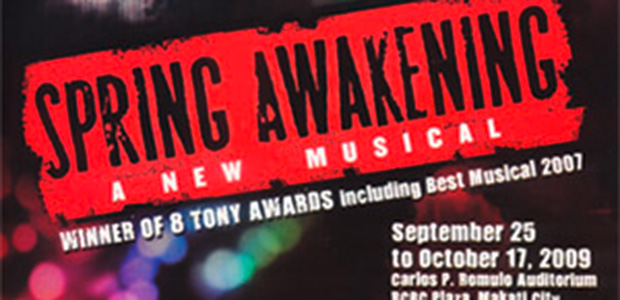

2. Spring Awakening, a rock musical directed by Michael Meyer, premiered on Broadway in 2006. It starred Jonathan Groff as Melchior and Lea Michele as Wendla. The production received universal critical acclaim, including eight Tony awards, four Drama Desk awards, and a Grammy for Best Musical Show Album.

3. In 2006, Tanghalang Ateneo staged an adaptation of Wedekind’s original, called Middle Finger Po. Directed by alumnus Ronan Capinding, the play featured four high school students struggling against an oppressive society.

4. In 2011, Atlantis Productions staged the first major Philippine production of Spring Awakening in RCBC Plaza. The staging featured a mixed cast of performance veterans such as Jett Pangan of The Dawn and Sitti Navarro of bossa nova fame, as well as fresh faces in the local theater scene.