A LONG AND WINDING ROAD. The path to priesthood probably takes more effort and education than the path to medicine or law. Photo by Ryan Y. Racca.

Before University President Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin, SJ decided to join the priestly ministry, he had a love life.

“She was in third year in UP… so I’d go to UP every so often,” he shares.

They would rendezvous in each other’s respective schools in the middle of schooldays and go out on romantic dates on weekends. They would talk incessantly about sweet nothings for hours on end on the telephone almost every evening—”telebabad,” as Villarin calls it.

But as his undergraduate years here in the Ateneo wore on, Villarin became busier and busier. In addition to his academic workload as a physics major, he became increasingly involved in the student government and soon became the head of the Ateneo Catechetical Instruction League.

“I realized come fourth year that I wasn’t able to spend as much time [with her] anymore as I used to. And then, we’d get into fights. Of course, I don’t blame her.”

“So, at some point, to be fair, I thought it would be better to let go—because otherwise, you become bitter, you become the person you’re not supposed to be,” he says. “We broke up in fourth year.”

Considering how he eventually became an environmental scientist for a Nobel Prize-winning body and president of the Ateneo de Manila University, one may argue that things have turned out for the best for Villarin. Nevertheless, as shown even just by the fact that he had to sacrifice a life of romantic love in order to become a Jesuit, it is clear that difficulties abound in the priestly life.

Given the religious’ renouncement of material possessions and commitment to chastity in the service of God and the Church, it would be an understatement to say that the priesthood entails much effort from those who decide to enter it.

Still, many Ateneans know little about the lives of the men of the cloth, despite the fact that they are the ones who run and preside over their university.

Discernment

Originally, Villarin had no intentions of becoming a priest. “It was never in my horizon,” he says. His parents, particularly his father, were very career-oriented and had wanted him to take up something along the lines of engineering or medicine.

But that all changed when he went to college. Being involved in ACIL, he taught catechesis to students studying in public high schools—forcing him to, as he put it, “know more about this Jesus Christ whom I was teaching about.” This, he says, opened his “mind and heart to the word of God.”

He also credits an immersion program he underwent as a third year college student that allowed him to live among farmers doing menial labor work. He says this heightened his consciousness regarding the plight of working-class Filipinos, and contributed to the formation of his convictions on social justice. In addition, his core philosophy classes brought about an existential crisis of sorts, forcing him to ask difficult questions regarding the purpose of his life.

This narrative of finding one’s way while still in college is likewise echoed by Philip Romulo, a pastor for Destiny Church, a Born Again Christian denomination.

“I became part of Students of Destiny way back when I was fourth year college in UP,” he says, in a mix of English and Filipino, referring to the youth arm of his Church in UP Diliman, where he was a computer engineering major.

In Romulo’s case, however, it was the charisma of the pastor that “won him over,” as he puts it, and inspired him to pursue the same career full-time despite having numerous job offers from information technology companies abroad. “[The pastor] is really my idol—his passion to win people, his passion for this nation,” Romulo says.

Cases like that of Villarin’s and Romulo’s—individuals who pursued highly technical degrees during their undergraduate years, only to find that college would only be complete with extracurricular activities—do not reflect the stories of all priests, though. Many young men who enter into the priesthood are dead set on it from the very beginning.

Such is the case with Earl Omega, a sophomore pre-divinity major, who says he had heard the calling of the Lord as early as his grade school days.

“I grew up in a very Catholic environment,” he says. “The calling defined much of my high school life.”

Proclaiming the news

After graduating from college and on the invitation of his former physics professor, Villarin went to Davao under the Jesuit Volunteers Program. Being away from family and friends in a region where he hardly knew the people and the language, he was able to think more clearly about what he truly wanted to do with his life. That allowed him to finally come to terms with his decision to become a priest.

“It was not easy, [I had] so many fears,” he says. “It was an act of faith—a leap of faith.”

When the time to finally tell his parents about his decision came, however, things did not turn out nearly as well. “My father did not talk to me. He was not there when I entered the novitiate,” Villarin recounts. “He said I was just brainwashed.”

But his parents saw early on that their son was unconventional, as he had veered in all sorts of directions during his undergraduate days. That helped them eventually come to terms with his decision. “They really gave me space. They had a clue already that things were different.”

Omega, too, experienced the same share of reactions from his family, particularly from his father, who he says was also reluctant. Eventually, however, like Villarin, Omega’s parents eventually relented, choosing to support their son in whatever decision he felt would make him happy. As for Omega’s friends, “They asked me ‘What about the money?’” he says, laughing.

A dwindling profession

As of late, however, the Villarins and Omegas of the world have increasingly become few and far between. The Catholic Church has been experiencing a crisis of sorts in that the number of young men deciding to enter the profession of priesthood has been dwindling.

Fr. Jose Francisco, SJ, president of the Loyola School of Theology, attributes this decline in part to the modern day phenomenon of increasingly small family sizes, coupled with a proliferation in the number of career opportunities available to young men.

“There was a time when traditionally, families would want one of their sons to be a priest, but that has changed with a smaller number of children,” he explains. “Then you have changes like possibilities for studies and work both here and abroad.”

When asked whether the Church’s conservative positions on social issues may have also been a factor in alienating an increasingly liberal and youthful demographic, Francisco insists that it remains to be seen whether or not a firm connection between the two can be established.

However, he is quick to add that the Church must be able to reach out to a contemporary audience without compromising on its core principles. “The only way the Church can evangelize, meaning fulfill its purpose of preaching the good news of Jesus Christ, is precisely by making that understandable and meaningful to people,” he says.

Even on issues such as the exclusivity of the priesthood for men, or the prospect of priests getting married, where the Church has traditionally held staunchly to its position of maintaining status quo, Francisco says that the Church’s views are continuously evolving.

“This is a complex theological question. On the one hand, you have to deal with [questions like] ‘What is the nature of the priesthood, of the priestly ministry? What is its function? Is this function compatible with having women there?’”

“You can see already that there are historical, theological, and cultural factors that come in. And that’s why you have this ongoing discussion,” he adds.

Stained cassocks

Apart from the contentious debates regarding religious teachings and social issues, the priestly vocation has also not been free from controversies of a worldlier kind. After all, being a priest does not necessarily equate to an immaculate life. In fact, it is not that difficult to point out priests who have committed acts antithetical to their vocation.

The Church has had to deal with the problem of priests who have sexually abused members of the laity. It is a controversy that has plagued the Church over the past century. Take for instance the case of the notorious Fr. Brendan Smyth, a priest from Northern Ireland.

In a BBC report, Smyth was convicted in 1994 on 43 charges of sexually assaulting children. What made matters worse was the fact that he was later convicted on 26 more charges of the same crime. Months before his death in 1997, he had admitted to another 74 charges of sexual abuse over a 35 year period.

Northern Ireland has not been the only place rocked by child abuse scandals. In the United States, hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent in settlements between dioceses and victims of child abuse committed by priests.

Much closer to home, a recent controversy has surfaced that linked the country’s zest for religion and illicit black market trade. In October 2012, National Geographic Magazine published “Ivory Worship,” an investigative piece by Bryan Christy that brought into light how Filipino demand for religious ivory figurines partly fuels the slaughter of thousands of elephants in Africa every year.

In the article, Christy specifically names Monsignor Cristobal Garcia to have connections to the illegal ivory trade. Christy explains, “Garcia gave me the names of his favorite ivory carvers, all in Manila, along with advice on whom to go to for high volume, whose wife overcharges, who doesn’t meet deadlines. He gave me phone numbers and locations.”

What could have been

Considering that they are individuals who have had to turn down opportunities so they could enter the priesthood, it is easy to think that priests probably hold even a tiny sliver of regret for their decisions. In the case of Romulo, who was a young professional climbing the corporate ladder, a prospect many Ateneans can or will be able to relate to, he says that his faith and his passion for the work it entails are more than enough to offset whatever regrets he may harbor.

However, he does admit that they do haunt him from time to time, especially when he juxtaposes his life against those of his peers. “They left and went abroad to finish their masters in Germany, or in National University of Singapore,” he says wistfully.

Omega also points out that there have been times when he was dissuaded from entering the priestly ministry. When asked why, he says, “I met a girl”—a situation Villarin would be familiar with.

“In a parallel universe, maybe I would be a family person now, with kids going to college,” Villarin says. “It would have been a good life.”

With reports from Paolo M. Taruc

The stages of Jesuit formation

Source: phjesuits.org

1. Pre-Novitiate (≤ 2 years)

– Exposure to Jesuit community and apostolic life

2. Novitiate (2 years)

– Spiritual Exercises

– Experiments and “Trials”

3. Juniorate (1 year)

– Studies in Humanities and Communication

4. Philosophy (2 years)

– Studies in Philosophy

5. Regency (2 years)

– Teaching Assignments

– Living in an Apostolic Community

6. Theology (4 years)

– Studies in Theology

– Preparation for Ordination

7. Ordination

– Priestly Ministry

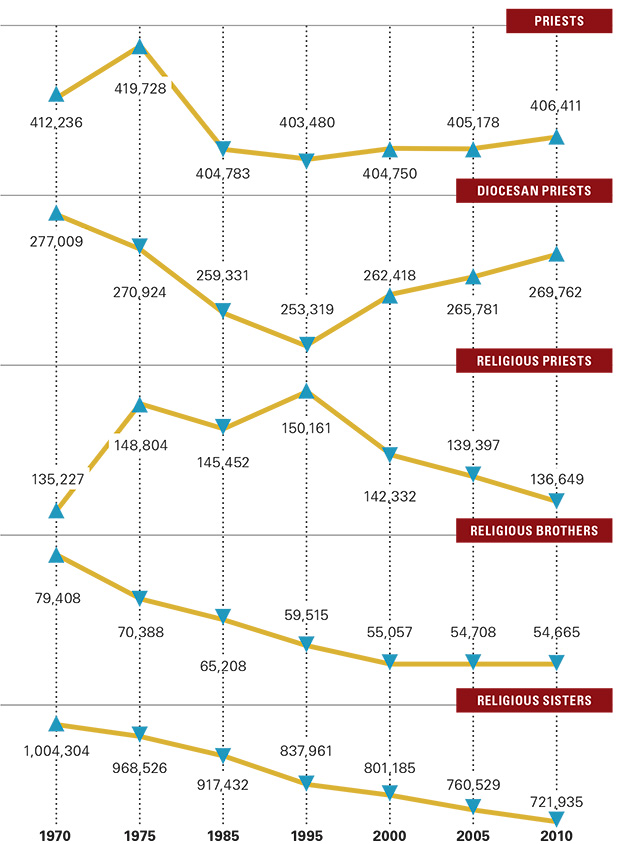

Catholic vocations by the numbers

Although statistics show a slight growth in numbers over the past few years, the global population of those in Catholic vocations has considerably declined from a few decades ago.

Research by the Inquiry Staff

Infographic by Shanice A. Garcia

Source: Georgetown.edu