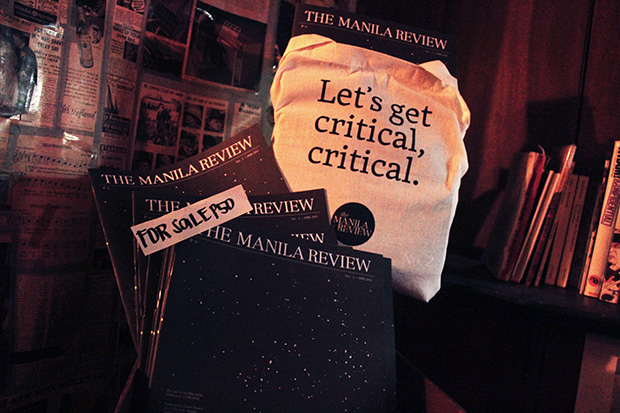

AN INTELLECTUAL FORCE. The Manila Review aims to heighten the level of critique in the country. Photo by Jessica L. Roasa.

The Filipino is a second class citizen in his own country—at least where film, literature and art are concerned. A substantial portion of the population favors foreign material over those which are locally produced almost without question. Founders of The Manila Review, Editor-at-Large Jojo Abinales and Editor-in-Chief Leloy Claudio (AB Comm ’09) are, however, looking to change that.

Perhaps the first of its kind, The Manila Review (themanilareview.com) is a monthly online publication that aims to provide its readers reviews of recent works on film, literature, art and everything in between. “There’s something for everyone,” says Claudio.

“We’re even planning on reviewing an economics book,” he adds, illustrating that the publication is open to almost anything. With their strong masthead comprising diverse intellectual heavyweights, it’s not a surprise that The Manila Review is garnering more attention than what they had initially expected.

Revving up reviews

Being avid devotees of foreign review publications like The New York Review of Books, Abinales and Claudio began The Manila Review in hopes of publishing a similar local publication that revolves around the discussion and chronicling of intellectual trends in the Philippines.

“There were a lot of sleepless nights,” says Claudio, a Political Science Department faculty member, on how the publication began. “I had no idea if the project was going to fly.”

He admits that this apprehension was due to the fact that The Manila Review admittedly only caters to a specific audience. To Claudio’s surprise, the publication’s followers grew, proving that more people than he had imagined were interested in the project.

Abinales, a professor at the School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, claims that it was his frustration with two things that ultimately led to The Manila Review’s inception. “First was the propensity of columnists who focus their reviews on American, not even European, books,” he says.

According to Abinales, Filipino titles don’t get enough recognition despite the efforts of local publishers like Anvil Publishing and New Day Publishers to promote them. “I found it odd and frankly irritating that these reviewers did not even care to take a look at these local publications,” he adds.

True enough, The Manila Review’s recent pieces include articles on various local media, including a film review on Marie Jamora’s Ang Nawawala and Tweet Sering’s chick lit novel Astigirl: A Grown Girl Living on her Own Terms.

Second, he mentions the moribund state of contemporary reviews in the Philippines. Abinales cites that most reviews should not be called such, as they are more of press releases than actual critiques. “In a lot of cases, what is supposed to be a review is actually an advertisement,” he says.

What sets The Manila Review apart from other review publications is the level to which it takes critique. A review becomes a stand, a perspective, an idea that can shape or even start an intellectual trend. “I want people to look back at [The Manila Review] and see what our generation was like,” Claudio says.

Form meets function

The Manila Review’s distinction from other contemporary publications, as articulated by Claudio, is its success in reconciling the gap between “short and punchy journalism” and long-form academic writing as found in journals. It lies in the middle of the spectrum—easily readable and consumed, but with a touch of intelligence that brings to mind an academic text.

“Our niche is that space between academic and newspaper-based reviewing,” explains Abinales.

This is further illustrated by the publication’s wide range of contributors, such as Ateneo professor Ambeth Ocampo, editor Jennifer B. McDonald of The New York Times, and Caroline Hau, PhD one of the country’s most prominent experts on Asian studies.

In most cases, The Manila Review allows its readers to see a different side to the publication’s renowned writers and editors. In contrast to her work in academic journals, for instance, Claudio describes a piece written by Hau for The Manila Review as “the same Carol” but with an infusion of humor and lightheartedness.

“A book review can be antipasto or dessert,” Hau writes in her article, “Reviewing the Reviewer.” “It may either whet the appetite or cap a meal. It may be dispensable to those who prefer to go directly to the main dish, but it can, at its best, enhance the pleasures of eating, the way dinuguan pairs with puto, green mango with bagoong, and wine with cheese.”

The Manila Review’s success however, does not rely solely on content. Going online has further distinguished it from other magazines because it does not have to rely on the distribution of print issues.

It was the unsustainable costs of print publishing that convinced Claudio to release The Manila Review online. “Big companies run these print publications,” he explained. Furthermore, a normal print cycle for a publication takes as long as a month to be completed—time that Claudio and his team couldn’t afford to spend sitting around and waiting.

The decision to launch online was a gamble that paid off, as it was met with positive feedback and critical acclaim. Designed by Ateneo alum Carina Santos (BFA ID ‘10), also the publication’s Design Editor, the website’s sleek and classic façade allows for the content to be the main focus.

“Barkadahan”

In his editor’s letter found on The Manila Review website, Claudio insists that with his editorial board’s strong, varying backgrounds and diverse political orientations, they strive to present a “plurality of views on politics and culture.”

With this ambitious goal comes a rigorous editing process: a piece goes back and forth from the writer to the editor, and Claudio says that even he has to go through this rigorous vetting. “Sending a piece means you get hammered by comments from intelligent people,” he says.

The publication mixes things up by putting together young and fresh journalists like Managing Editor Mara Coson, an editor at local publication Rogue, with more established writers like Senior Editor Shiela Coronel, one of the founders of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). The strategic selection of senior academics and young journalists invites an intergenerational audience. The holistic discussion of ideas comes from both a classical and a contemporary perspective.

There are, of course, those who disagree. National Anti-Poverty Commission Assistant Secretary Lila Shahani expressed her disappointment with The Manila Review through social networking site Facebook last January 6, on the publication’s supposedly one-sided interview with writer Katrina Stuart-Santiago about her controversial piece on the Philippine literary scene in Rogue’s April 2012 issue.

Claiming that she had high hopes for the publication, Shahani says that after reading its first issue, she found it “sadly biased and lacking in rigor.” She also pointed out that the publication is just “barkadahan”—all fluff and nothing more.

Claudio, however, says he’s used to online arguments and that he is unaffected by these criticisms. “I’m too thick-skinned,” he laughs.

“We’re not trying to be gatekeepers or some influential barkada,” adds Editorial Assistant Job De Leon (AB Comm ’12). “Hopefully, we’re able to contribute to the way people think.”

Moreover, Claudio is open to listening to The Manila Review’s critics, and has even considered working with them. “As Mara [Coson] always says, [The Manila Review] is like an indie band,” Claudio remarks. “We just keep playing and playing.”

Simple dreams

Not every Filipino author is a Samantha Sotto or a Miguel Syjuco whose works get published by big-name publishers like Random House. Local authors struggle to get their manuscripts in the right hands. Even then, there’s no guarantee that their work will be successful.

Abinales hopes that The Manila Review will encourage its audience “to read the books we review and to also make them aware [of] how rich the Philippine publishing tradition is.”

“My ultimate dream is for someone to go into National Bookstore or Powerbooks and head straight to the Filipiniana section,” he says. “[My dream is] to see the Filipiniana section occupy the largest space in all bookstores because of a strong demand by Pinoy readers. We envision [The Manila Review] as contributing to this effort.”

Perhaps more funding and a stronger following will allow The Manila Review to do just that in the long run. At present, the publication is simply the start of a conversation: one that invites Filipinos to join in and to raise the bar on criticism and discourse in the country.

After centuries of foreign dominance in many aspects of culture in the Philippines, perhaps it’s Coronel who puts it best in the website’s “About” page: “It’s about time.”