Before the first semester begins, Henry Lee Irwin Theater is filled with new faces. During the annual orientation seminar, Ateneo freshmen are bombarded with all sorts of information, like names of buildings, untouchable benches, what “TBA” means and the like.

One thing that the administration never fails to pronounce, however, is how special the new batch of Ateneans are: they are the “cream of the crop” and the “best of the best.” This sort of impression is placidly accepted, but one thing seems to stick—because of their stay in the university, they will definitely have a brighter future.

Even before acceptance, applicants are already made to think that if they graduate from the Ateneo, they are already guaranteed a job. This notion seems to be reinforced not only by the university, but even by society in general, through the simple reputation of the “top four” schools that are supposed to provide the best education in the country.

With the amount of Ateneo alumni who are successful in business and other fields, Ateneans believe that they made the right decision in choosing their university over all others when it comes to prospects of employment. But when the mad scramble for jobs begins, they are thrown into doubt—has studying in the Ateneo really made a difference?

An Ignatian education

The Ateneo is known for its core curriculum. Though the University of the Philippines (UP) has its general education (GE) subjects, the Ateneo has a more rigid system when it comes to its implementation. UP requires that students take a certain amount of GEs before they graduate and it is up to the student to decide on what classes to take. The only strict requirement set by UP is the amount of GE units to be taken, which is course-specific.

A student’s first year in Ateneo is spent on most of the core subjects: natural science, math, English and literature. According to Jules Jurado (BS ME ’12), these subjects certainly made the transition from high school to college education much easier. As the years pass, a student’s basic load per semester is divided between core subjects and the major subjects.

Edward Villarosa (BS CTM ’12) says that the core subjects are often perceived more as a “burden than a blessing,” but that what is taught in these core subjects “can really get into your head, and it’s not such a bad thing.”

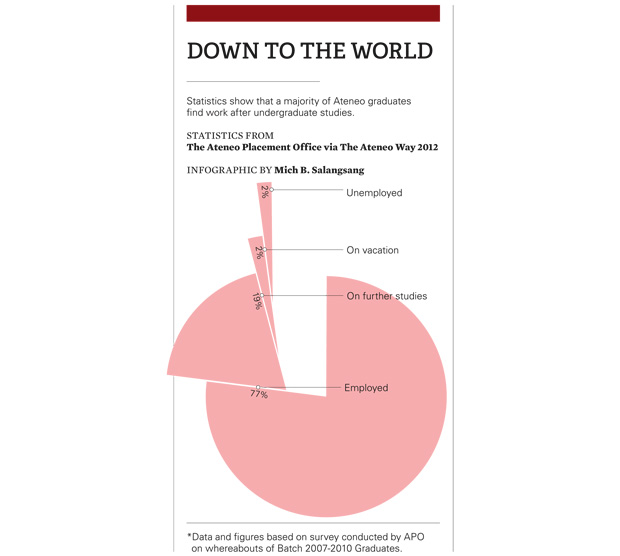

According to the statistics of the Ateneo Placement Office (APO) published in the 2012 issue of The Ateneo Way, 77% of Ateneans that graduated from 2007 to 2010 are currently employed. Out of the graduates from 2007 to 2010, 19% went on to further studies and 2% went on vacation. The other 2% are currently unemployed. Some graduates opt to take further studies in the search of better opportunities, while some go on to study medicine or law.

What cannot be answered by the statistics, however, is how long these fresh graduates had to wait before finally getting a job, or, say, how many of them simply worked for their family businesses. Villarosa falls into the last category, though only he out of his three siblings decided to work for the family business. He isn’t the type to rest on his laurels, however, and is happy that his father doesn’t give him any special treatment and wants Villarosa to work from the ground up.

Living in the “real world”

Aside from the troubles of searching for a job, there are some fresh graduates who also have to face difficulties in supporting themselves as they live independently in Metro Manila. Such is the case for Jurado, whose family is currently based in Bacolod City. “Choosing to live in Manila involves daily sacrifices, such as budgeting in order to meet daily needs and, at the very least, have a decent amount of savings,” he says.

Fresh graduates who have already been based in Manila to begin with at least have a home to live in, and most of the time, have their parents nearby to depend on for food and other utilities.

Jurado not only has to spend for transportation and pay rent, but has to do so off his own earnings, which is usually not too great for fresh graduates. “(Now) I live independently from my family and have to learn things from the ground up and can only live within my means,” he adds.

His time in the Ateneo has made quite a difference in his life, though, and he is sure it is the same for most of his batch mates. “The core curriculum lends itself toward a life of critical thinking,” he says, and has his philosophy and theology classes to thank for his ethical standpoint in living.

Marc Pasco, who teaches with the Philosophy Department, concurs, saying that perhaps one reason the Ateneo is chosen by most high school graduates is because “May mas humanistic na angle ang edukasyon. (The education is more humanistic.)”

For example, a core subject required of Atenean students is Philosophy 104, or the Foundations of Moral Value—a course which focuses on ethics. Pasco says that this is one of the reasons the Atenean education stands out—because students are made to think of how they want to live their lives after graduating and further along the line, and what kind of culture they want to build their futures in.

Whatever Ateneans learn about ethics, or even about things distinctly emphasized in the Ateneo, such as social entrepreneurship, is difficult to put in good use once Ateneans are thrust into the “real world.” Outside the Ateneo, the dominant culture is one where there is great pressure to succeed, and the “losers” fall by the wayside.

Villarosa says that what sets the Atenean education apart from others is that the students learn about ethics. “Ateneo wants us to find the place where our passion and financial stability intersect,” he says.

Getting a “good” job

One issue some Ateneans face is the problem of being underemployed. While other graduates would welcome acceptance to any company because of the promise of stable income, some Ateneans may turn down offers because the pay is too low for their standards. This is, admittedly, very subjective territory—Jurado and Villarossa both shy away from directly answering the question, “Do you think Ateneans have a sense of entitlement when it comes to selecting employment?”

As previously stated though, relatives, friends and even the university itself tend to perpetuate the idea that when you graduate from the Ateneo, you will immediately get a job. What students may think varies, but they usually fall prey to the idea that whatever job they get will be a “good” one, meaning good pay and good benefits. Once again, however, we see the subjectivity of the matter—what precisely counts as “good”?

For Jurado, it means being able to support himself financially and still have enough savings. The idea of a sense of entitlement is not new to him, however. “Some may see education as an investment and therefore expect higher returns after spending years in the Ateneo,” he explains.

Though the issue of student debt is not as prevalent in the Philippines as it is in the United States, it is true that most parents expect their children to have a higher standard of living after finishing with an expensive Ateneo education.

Status quo

An Atenean may be equipped with enough knowledge to be effective at his chosen line of work, and hopefully equipped enough to live ethically, but it is, as with most things, easier said than done. The business world, for example, is known to be ruthless—the saying that “greed is good” isn’t too far off the mark when it comes to the world of money-making.

Though this cutthroat environment is not in sway in the Ateneo community, fresh graduates on the hunt for jobs usually search for the job with the highest pay and the most comprehensive set of benefits. This is not something that Ateneans should feel any ill will for—after all, it is natural to search for what is thought to be the best for oneself, Jurado says.

According to Pasco, however, what really matters is what these fresh Ateneo graduates do after: “Yung tanong na, ‘Eh ano ngayon na marami ka nang kotse, maraming bahay, ano ‘yung epekto mo sa ibang tao?’ (It’s that question, ‘Now that you have a lot of cars and houses, what is the effect of your life on others?’)”

One thing Ateneans can take pride in, then, is something they had hopefully picked up in one of their numerous core classes—the constant questioning of their selves, as Pasco says.

“May napaunlad ka ba na iba sa sarili mo? ‘Yun ‘yung angulo na meron ang Atenista, sa tingin ko, na baka wala o maliit sa iba. (Are there others apart from yourself who have also grown thanks to your doing? That’s the angle that Ateneans have, I think, that may be lacking or missing in others.)”

Some Ateneans forego of the idea of working for a private corporation. Jurado says that he has batch mates working for the Philippine Government and non-profit organizations who tell him, with no airs at all, that they believe that that is where they are most needed and where they can make the most change.

On the other hand, graduates who choose to work in the corporate world are faced with other challenges. Pasco says that it is so easy to lose sight of what is ethical because of the culture of business.

He hasn’t lost hope, though, saying that because of the habit of reflection instilled in Ateneans, such as in philosophy and theology classes, Ateneans will reach a point where they will ask themselves, “Where is my life really going?”

Upward struggle

A verse in the “Song for Mary” begins with the iconic line, “down from the hill.” Ateneans can liken this image to their own graduation.

It is in going down the hill, so to speak, that fresh graduates face the trials and tribulations of the real world—where they have to not only secure employment, but also learn to juggle a plethora of responsibilities.

Going down the hill is the easy part. What is often left out of the metaphor is how employment is itself another slow climb. In such a climb, it is the application of education—of values and ethics in decision-making—that makes life more difficult.

Even though the university does its best to provide proper preparation for students, ultimately, an Ateneo education is supplementary to the way Ateneans conduct themselves after graduation.