STREET ELEMENTARY. Street children deprived of basic education often spend their days begging for alms. Photo by Benjo T. Beringuela

High-rise residential condominiums, popular commercial establishments and some of the country’s prime educational institutions can be found along Katipunan Avenue in Quezon City. It is a place where students and young professionals flock and carry out their daily activities.

But a different world also exists in the same busy thoroughfare. Katipunan plays host not just to private school students and the employees of the many establishments in it, but to street children as well.

Tough lives

Street children are defined as young people living and/or working on the streets. They are generally five to 18 years old, and may or may not be under the care or protection of adults. The United Nations Children’s Fund identifies two main categories of street children: children “on the street” and children “of the street.”

Roselda is one of the children “on the street” of Katipunan. Such children are the ones engaged in any kind of economic activity. From 8:00 AM to around 5:00 PM, Roselda sells banana cue near Starbucks. She spends the night playing with the other street children in the area, and returns to her home in Daang Tubo where her mother would be waiting for her.

According to the Loyola Heights Barangay Captain Caesar Marquez, most street children in Katipunan are not homeless. A number of them come from Barangay Pansol and the residential areas surrounding the University of the Philippines. They are brought along to Katipunan by their parents to work or beg.

“Katipunan attracts them,” says Marquez. “The place is commercialized. We have a lot of restaurants and other establishments here, and students are just everywhere.”

In many other cases, these children are also brought by their parents at night to scavenge garbage for a living. “When the parents are caught [by law enforcers], they are usually accompanying their children. The scavenging of garbage is not allowed in Katipunan,” Marquez adds in Filipino.

On the other hand, eight-year-old Christian is a typical child “of the street”—those who do not have a house to live in or return to at the end of the day. Christian’s older brother is the only family he has known. He never met his parents. The two of them have been living on the sidewalks of Katipunan for as far as long as he can remember. Since his brother is unemployed, begging from students passing by the overpass in front of a bookstore is the only way that they get by.

Vulnerabilities

Kenneth Abante (BS ME ’12), Loyola Schools class valedictorian of 2012, shares the story of Jen*, a street child in Katipunan who passed away. In a June 2012 report of The GUIDON, Abante, who is now working for the government, was featured as saying that he was inspired to serve by two street children from Katipunan who gave him a birthday greeting card.

“Jen was a good friend,” Abante says.

“She died due to gastrointestinal complications. She already had a stomach ailment before because of hunger and food quality, but it was only mild,” he explains in a mix of English and Filipino.

According to Abante, Jen’s experience is not rare for urban poor families. Even in cases where the children are brought to the hospital, there is little guarantee of recovery due to the high cost of medicine.

Marquez also voices out the same concern. He claims that there is no lack of literacy programs and other such efforts in the area, but the problem of hunger, health and the lack of shelter continue to be severe.

“Pag dating ng gabi, wala rin naman silang kakainin. Kung walang makain, walang mag-aalaga, walang mauuwian, wala ring kwenta ang mga programa natin. (When night comes, [urban poor families] don’t have anything to eat. When there’s nothing to eat, there will be no one to take care of the children. When no one takes care of the children, there’s no point in them going home. When that happens, our social programs become useless.)”

Safe haven

Barangay Loyola Heights identifies a total of 26 street children on the streets of Katipunan. Out of this number, only six have originally resided in the thoroughfare. The rest come from UP, Barangay Pansol, Marikina and Antipolo.

The barangay stresses the need for shelter homes in Quezon City. Currently, there are tie-ups with child care centers in other areas where the street children roaming Katipunan are turned over, but it is not uncommon for the barangay to receive reports of these children escaping.

“The street children are not accustomed to the rules and regulations of the shelter homes,” explains Shavanie Pimentel, program coordinator of Barangay Loyola Heights. “Tumatakas sila tapos bumabalik sa Katipunan kasi mas marami silang nakikitang opportunities dito. (They escape and go back to Katipunan because of the many opportunities they see in the avenue.)”

Pimentel maintains that it is necessary to have a shelter home in the area in order to prevent the children from being susceptible to disease and malnutrition, abuses and sexual exploitation. Furthermore, reducing the number of children on the streets will also prevent criminal activities, particularly theft.

Marquez says that some street children in Katipunan are involved in such activities, commonly stealing cell phones and laptops from students.

“It will be very helpful [to have a shelter home in the area],” he admits. “We’re working it out. Sana matulungan kami. (I hope we get help.)”

Vertical relationship

The Philippine government frowns upon the giving of money to street children. Presidential Decree No. 1563, otherwise known as the Anti-Mendicancy Law, prohibits begging.

Arthur Buena, Education and Spirituality Officer of the Ateneo Student Catholic Action (Atsca), believes that there is nothing wrong with extending help to the less fortunate children through small acts of generosity as long as we do not see them as mere beneficiaries, but as human beings.

“They’re just kids. It’s most likely that they’re still independent,” says Buena in a mix of English and Filipino. “In our obsession with doing what we think is right and just, we sometimes forget the value of compassion.”

Abante shares the same sentiment. According to him, it is not proper to give large sums of money for the benefit of these children without getting to know them first. “It’s a marginalizing act,” he says. “We need to listen to them. We need to get to know them first before we help.”

NO PLACE TO GO. Many street children have no choice but to sleep in thoroughfares at night. Photo by Benjo T. Beringuela

Changing lives

Efforts to help street children may end up marginalizing them more. However, Abante explains that the other extreme end is apathy and indifference.

“Lagi na lang tayong nakakakita ng street children. (We always see street children.) As a result, some of us don’t find the issue as urgent anymore,” he points out. “But it is. [The] problems [of street children] are most of the time pretty urgent.”

Fortunately, the Ateneo community and Barangay Loyola Heights have a number of projects that aim to promote the welfare of street children. As a matter of fact, Katipunan is now said to be in the “prevention stage.” The Barangay Council for the Protection of Children takes care of those who are “at risk” of becoming street children by enrolling them in the Interactive Children’s Literacy Program, where they are regularly monitored.

Atsca’s flagship project, the Personality Enhancement Program, provides alternative learning classes by creating tie-ups with other organizations. “Last time, we partnered with Bluerep [Blue Repertory]. We sold tickets for them, and in return, they taught the kids theatrics,” says Buena.

Other projects of Atsca include medical missions and area overnights that would allow members to get to know the community more.

Changing perspectives

“To clear out: not all suffering is dire,” says Abante. He explains that the problem with the way we look at the issue of street children is that all we usually see is suffering.

Abante recalls what he has learned from his philosophy classes with Jope Guevara. “You have to [do] away with the Messianic Complex, thinking you’re a messiah saving everyone. We are all invited to go out there and consider their entire experience, which is so much more than just suffering.”

He further cites the case of Jen, who was, as a matter of fact, forbidden by her father to stay out on the streets. However, she continued doing so because her friends were there.

“We have to reflect on their enjoyment and generosity. As Bobby Guev also said, usapan ng pagtingin iyan (it’s a matter of perspective)—how you help them and how they also help you,” Abante says.

Buena believes that, for some people, poverty has become faceless. “We see street children just as kids we’re supposed to help. Worse, some people see them just as statistics.”

“Kailangan nating bigyan ng mukha ang kahirapan. (We need to give poverty a face,)” Buena says. “Para maintindihan natin na tao din sila at pare-parehas lang tayong may problema. Kung kaya nating maging masaya, kaya rin nila. (So that we would know that they are human beings just like us, and that we all have our own set of problems. If we can be happy, so can they.)

- STREET ELEMENTARY. Street children deprived of basic education often spend their days begging for alms. Photo by Benjo T. Beringuela

- NO PLACE TO GO. Many street children have no choice but to sleep in thoroughfares at night. Photo by Benjo T. Beringuela

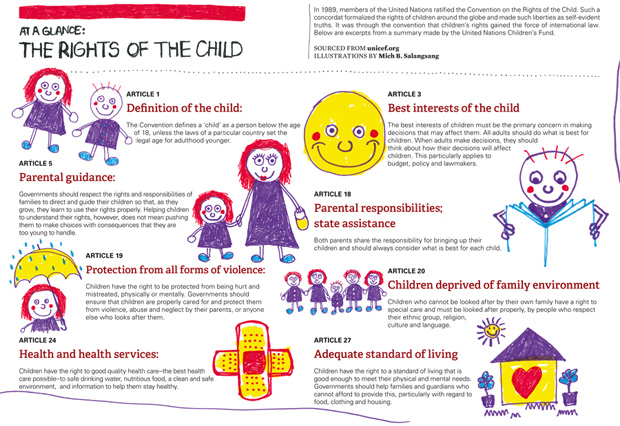

At a glance: The rights of the child

In 1989, members of the United Nations ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Such a concordat formalized the rights of children around the globe and made such liberties as self-evident truths. It was through the convention that children’s rights gained the force of international law. Below are excerpts from a summary made by the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Article 1 (Definition of the child): The Convention defines a ‘child’ as a person below the age of 18, unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood younger.

Article 3 (Best interests of the child): The best interests of children must be the primary concern in making decisions that may affect them. All adults should do what is best for children. When adults make decisions, they should think about how their decisions will affect children. This particularly applies to budget, policy and lawmakers.

Article 5 (Parental guidance): Governments should respect the rights and responsibilities of families to direct and guide their children so that, as they grow, they learn to use their rights properly. Helping children to understand their rights, however, does not mean pushing them to make choices with consequences that they are too young to handle.

Article 18 (Parental responsibilities; state assistance): Both parents share the responsibility for bringing up their children and should always consider what is best for each child.

Article 19 (Protection from all forms of violence): Children have the right to be protected from being hurt and mistreated, physically or mentally. Governments should ensure that children are properly cared for and protect them from violence, abuse and neglect by their parents, or anyone else who looks after them.

Article 20 (Children deprived of family environment): Children who cannot be looked after by their own family have a right to special care and must be looked after properly, by people who respect their ethnic group, religion, culture and language.

Article 24 (Health and health services): Children have the right to good quality health care–the best health care possible–to safe drinking water, nutritious food, a clean and safe environment, and information to help them stay healthy.

Article 27 (Adequate standard of living): Children have the right to a standard of living that is good enough to meet their physical and mental needs. Governments should help families and guardians who cannot afford to provide this, particularly with regard to food, clothing and housing.

Source: unicef.org