It comes to the Atenean like a religious code—quote your sources, eyes on your own paper, verify and cite. Those who don’t are thieves and liars. A core principle of the Ateneo’s academic tradition rests in one’s obligation to ensure the academic integrity of his or her own work. The Loyola Schools Undergraduate Student Handbook, for example, explicitly states that a proven act of academic dishonesty is a major offense.

Although it seems that the majority of the student populace adheres to the college’s academic code, there exists a number of individuals who manage to break the rules and get away without as much as a slap on the wrist. They operate on a mindset where honesty takes a backseat for the sake of money, grades or the thrill of not getting caught.

A method to secrecy

Jonathan*, a third year student, used to earn money writing papers for other students. “People will be willing to pay anything from P200 to P500 for your usual [three- to eight-page] non-research papers,” he says. “Research papers usually go for more.”

He explains how people avoid getting caught: “The thing with paying someone to write your paper is [that] you’re pressured to [keep] paying the same guy to write the rest of your papers. So, it’s consistent.”

When it comes to cheating in the classroom, old practices such as writing down notes on one’s handkerchief or hiding them at the back of calculator covers have given way to more elaborate and discreet methods. Jonathan shares how he used to “Photoshop” cheat-sheets on fake soft drink bottle labels. He is quick to point out, however, that he did these things more for the “daringness factor” rather than getting a high grade.

“Simple cheating is always much better if you’re just after the grades. [It’s] always just about discretion. Teachers don’t really peer over your shoulder [all the time] during tests,” explains Jonathan.

“Waste of time”

There are those who believe that the university’s academic code creates an environment that is not conducive to the freedom of thought. Take the case of Marco*, an alumnus of the Loyola Schools and a current student of the Ateneo Law School.

Marco disagrees with the practice of attribution, arguing that such an act discourages students from thinking for themselves. “Why does it have to be in a book before an idea is credible?”

“So, to make an argument, you just look for a book [that argues] your side,” he says. “Then suddenly your idea becomes credible—because without the book, [your] idea is shallow and un-researched.”

“[It’s a] waste of time. Instead of thinking more, [you] spend more time looking for the book that says the same thing.” Although Marco claims to have never cheated, he narrates the time when he submitted his undergraduate thesis paper without any research or cited sources.

When asked by his teacher why he did not attribute material, he explained that there simply was none for him to use. As a consequence, his thesis grade was dropped from an A to a B/C+.

A rigorous procedure

A typical investigation on academic dishonesty does not follow a strictly linear process. Associate Dean for Students Affairs (ADSA) Rene San Andres talks about two cases to show the many directions that such can go.

In the first case, a written statement by a student suspected of plagiarism presents clear arguments that he or she had no intention to commit such an act. After initial inquiry, the ADSA Office returns the case to the student’s teacher for re-evaluation. It is up to the teacher to decide whether or not such a case has to be pursued.

In San Andres’ second example, a student admits to outright plagiarism. Such an act prompts his office to decide on a proper punishment which, more often than not, ends in a suspension.

The possible suspension, as well as its length, is decided upon after taking certain aggravating or mitigating factors in the case into consideration.

San Andres points out that one aggravating factor is willful violation, which stands in contrast to an accidental violation. Another example is conspiracy, where other students are involved in committing an offense. Furthermore, his office looks into a student’s refusal to admit guilt in the face of overwhelming evidence.

Consistency

English Department Assistant Professor Danilo Reyes mentions that a primary indicator that would help determine whether or not a student’s work has been plagiarized is the style consistency of the text itself. “Given a semester’s time, you become familiar with a lot of things: what words a student is likely to use, what are the thought processes of the students… You see that in the writing, the recitation.”

Reyes has been teaching in the university since 1989. He filed his last major case over a decade ago.

“Sometimes, it’s as practical as getting that whole paragraph and dropping it in some search engine like Google, and you find out right away that it is unoriginal material.”

It is the teacher’s discretion to decide whether or not cases of academic dishonesty get raised to the ADSA. Some, including Reyes, take into consideration whether the violation occurs in a major or minor requirement.

Upon suspicion, Reyes points out that he never fails to approach students and discuss the matter personally. What is important for him is that they understand the gravity of the offense.

Owning the work

Having been a part of the academe for more than two decades, Reyes understands that not all students adhere to the value of academic integrity as much as a member of the faculty would.

“As a teacher, [I could assign a research paper and] I could choose to be indifferent about it. It makes a difference if you spend some time enticing students to own the activity as part of their integral growth.”

Hence, he argues that teachers must find a way to go beyond mere requirements and instill to students an “I need to do this” attitude. It is by doing so that a student begins to find ways to add “texture, color and complexity” to his or her work. “If a teacher manages to do that, then the premise or the assumptions regarding originality are really kept in place.”

It follows, he says, that one learns to appreciate the labor of others.

Just like Marco and Jonathan, there are students in the Ateneo who believe that the standards of academic integrity constrict work. Reyes calls such nonchalant students as “special cases for the teacher.”

A matter of character

“There are tough ‘test cases’ that a student could find himself in after the university—[they] will establish his academic integrity,” Reyes says, pointing to the prestigious environment a student may be immersed in after graduation. “[Let’s] say you are well-known, and a whole lot of people read what you write. A lot of those people, being in a high-profile environment, have a keen sense of scholarly concern.”

“If… you do not have the scruples to practice observing seemingly little and inconsequential things that would buffer your integrity, those things will show,” he adds.

San Andres agrees, calling academic integrity the “lifeblood” of a university.

He emphasizes the role of the Ateneo in raising future leaders. “Academic dishonesty may just be a symptom and a feedback to the student that… if you can so casually lie in an academic setting, [there] would be a trust issue. Will you be trustworthy enough for the country to hand over to you decisions that would affect the lives of thousands, perhaps millions of people?”

Ultimately, however, it may just be about being Atenean, which San Andres defines as an identity dedicated to the service of others. “Can you trust a liar to serve the future of this country?”

San Andres stresses the importance of rigor—focusing on students who committed academic dishonesty due to a lapse of judgment. After all, he says that the most important reason for academic integrity is the aspect of character formation. “At the end of the day, the student, [once he graduates], is still the same person.”

*Editor’s Note: Names have been withheld upon request.

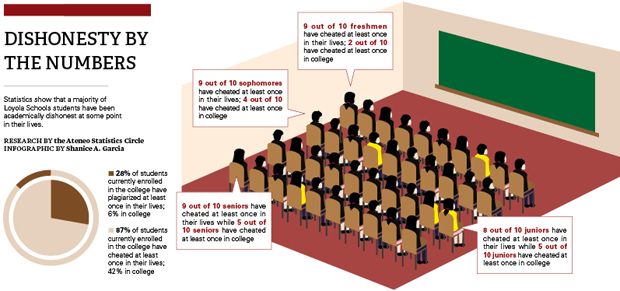

Dishonesty by the numbers

Research by the Ateneo Statistics Circle, Infographic by Shanice A. Garcia