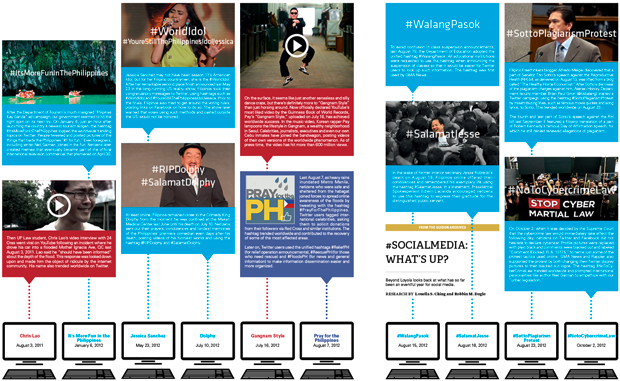

THE BIRTH of the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (RA 10175) caused panic in cyberspace and crashed into the digital screens of Filipino netizens last September 12. The act elicited violent reactions, not only from national politicians but also from the larger online public. Now, amendments to the act are being proposed due to claims that the law violates rights guaranteed by the constitution.

Sources and masterminds

In a Senate press release on September 16, the main proponent of the controversial law, Senator Edgardo J. Angara, called the passage of the act “a milestone for Philippine ICT (information and communications technology).” However, in a Philippine Daily Inquirer article entitled “Sen. Angara takes responsibility for cyberlaw” published last October 4, Angara admitted fault in “some omissions” in the passage of the act.

Angara is not the only author of the law. He told the Inquirer in the same article that among the law’s proponents were Senate President Juan Ponce-Enrile and senators Jinggoy Estrada, Loren Legarda, Miriam Defensor-Santiago and Antonio Trillanes IV.

Flaws and remedies

A temporary restraining order (TRO) suspending the implementation of RA 10175 for 120 days was issued by the Supreme Court (SC) on October 9.

Lawyer Toby Purisima (AB Philo ‘01) was part of one of the many groups that filed for an issuance of a TRO. He said in an interview that he pushed for a TRO to be issued because, despite the relevance of the act, it had provisions that needed to be amended.

The petition for TRO he submitted along with his group, which included fellow lawyers, argued that the following sections of the Constitution have been violated by the act: the rights to due process of law and equal protection of law; the right against unreasonable searches; the right to privacy of communication and correspondence; the right to free speech expression; and the right against double jeopardy.

Purisima proposed that the following sections of R.A. 10175 be revised: Sec. 4(c)(4): Criminalizing “cyber libel”; Sec. 5: Punishments for acts that aid offenses under this law; Sec. 6: Imposing a higher penalty for any offense committed under this law; Sec. 7: Prosecution under this law is non-prejudiced; Sec. 12: Authorizing any and all law enforcement authorities to collect data from any electronic device with or without prior judicial warrant; and Sec. 19: Authorizing DOJ to block access to computer data that violate the law.

Purisima added, “There’s a doctrine in law that whenever the government wants to curtail or to stop or to prevent a right, it should only do what is necessary to prevent that and shouldn’t do anything more than that. But in this case, it uses a ‘bazooka to kill an ant.’” He claimed that the law is “too good” that it overreaches.

Aside from overreaching, the law, Purisima said, is also causing a sense of fear that “it’s like an axe, constantly hanging on top of our heads that the government may strike at any time.”

Rebuttals and rallies

Netizens have made online protests themselves. A group of “hacktivists,” claiming to be part of the local chapter of the loose global hacker collective Anonymous, took temporary control of several government websites on October 1. Many Facebook users also set their profile pictures to black in protest of the act, as encouraged by a group called Philippine Internet Freedom Association.

Giving his opinion about the hacktivists’ actions, Lisandro Claudio, assistant professor at the Political Science Department, said, “Nobody’s getting hurt, nobody’s dying or anything. These are temporary shutdowns, and they’re acts of symbolic warfare.”

He pointed out that though what they are doing is illegal, it is not immoral. For Claudio, their act is a form of civil disobedience and active non-violence.

Claudio also expressed his full support for the “Black Profile Picture” campaign, as he sees it as a way to show that Senator Tito Sotto—who allegedly added the online libel section to the cybercrime law—“is being misguided when he thinks he can take on the internet.”

Comparison and contrast

Brian Paul Giron, a faculty member of the History Department and the Twitter user behind the #SottoPlagiarismProtest hashtag that trended on the micro-blogging site late last August, compared the implementation of the cybercrime law to the situation of the country under Martial Law.

He said that the act “brings back [Martial Law] into the limelight, something that Marcos legislated so that his police state could look into people and of course harass people. This is now being summoned by our current government in cyberspace.”

Meanwhile, Chay Hofileña, a faculty member of the Communication Department and director for citizen journalism and community engagement at Rappler, shared the same sentiment.

“Without proper safeguards, abuses can be easily committed and privacy violations can be easily made,” she said. “The situation can be no different from the 1970s when the state had absolute power to prosecute individuals who were considered unfriendly or unsympathetic.”

However, although a response to the law can be mapped out in legal ways, a simpler way to resist the cyber trap is simply to speak up—though in the proper manner. “I think the solution is discourse, to talk about the merits of the law and to properly verbalize [what’s wrong],” said Giron.