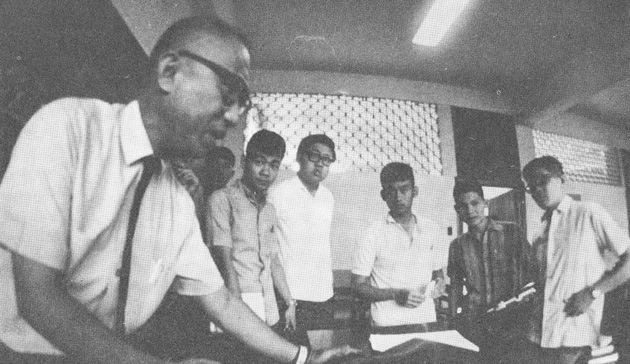

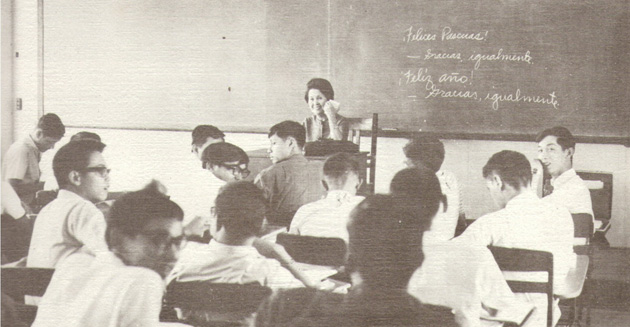

ENTONCES. Foreign languages have been a staple of the curriculum long before the instruction of Filipino. Photo from Aegis ’68 and ’69, Courtesy of the University Archives

Throughout the Ateneo’s contemporary history, the entire project of nation-building has become a core thrust of the university. Hence, the community has been hard at work in recent years trying to live up to its vision for itself as a home of nation-builders. There is a legacy to continue, after all—the university prides itself on having produced generations of alumni who have gone down the hill and promoted positive change in Philippine society.

One must take note, however, that the community is not in consensus about any one notion of nation-building. There are those who stand bemused at such a paradigm, believing that a discourse no longer rooted in Filipino culture has developed in lieu of one that caters to the Philippine situation. In the university’s commitment to nation-building, one integral question is seldom asked—what kind of nation are we building?

More than four decades have passed since the famous student manifesto, “Down from the Hill,” was published in The GUIDON. Written by five Atenean undergrads—Jose Luis A. Alcaraz (AB ’70), Gerardo J. Esguerra (AB ’70), Emmanuel A. F. Lacaba (AB ’70), Leonardo Q. Montemayor (BS ’70) and Alfredo N. Salanga (AB ’69)—the manifesto called for the Filipinization of the Ateneo, claiming that national development demands a new orientation that was truly Filipino.

The supporters of Filipinization believed that the university must realign itself to be in a position relevant to the Filipino. “We find the Ateneo developing in the line of a university attuned to the standards and conditions of Western society,” the manifesto read, “when the revolutionary situation demands service for national development, in terms of Philippine standards and conditions.”

Much has changed since then. One cannot doubt that the university has undergone major transformations, in the trail of the movement that the manifesto inspired. Filipinization has, for years, imbued the university with a distinct spirit, animating it all the way to the new millennium and beyond. However, the current era is presenting new challenges that call for a fresh response: it poses the question of what it means to be truly Filipino in an increasingly globalized world.

Filipino identity

Past attempts in Filipinizing the university have paved the way for reforms which endure up to this day. Efforts to immerse students in Philippine culture and local realities outside the campus include drastic changes in the curriculum and integrated learning, as well as in non-academic service programs. Prime examples of such include the availability of philosophy subjects in Filipino, as well as the immersion program for the school’s senior students.

For Agustin Rodriguez, PhD, chairperson of the Philosophy Department, teaching philosophy in Filipino facilitated a deeper understanding of Philippine reality. “It really changed the way we think,” he says. “The fact that we teach in Filipino—and some of us research and write in Filipino—changed the way we philosophize. Although the basic framework is still Western, we now feel more culturally rooted.”

The university also boasts of a rich humanist tradition. The literature and art programs of the school perhaps serve as some of the strongest vehicles for the expression and promotion of Filipino culture and traditions in the country. The Ateneo Art Gallery continues to be the premier museum of modern art in the country, boasting a wide collection of works by foremost Filipino artists.

Internationalization

The university also aims to be an academic institution that is globally recognized. Much attention is given to promote international linkages and academic partnerships. Student exchange programs offer an array of opportunities for students to learn abroad and expose themselves to global culture.

“It is a great opportunity to learn more about other cultures and gain new perspectives,” said Joyce Te, a junior legal management student who had recently participated in an exchange program with Singapore Management University. “I experienced the best of both worlds—Singapore being a developed country and the Philippines a developing country—and it made me more appreciative of our own country.”

The university has performed well against other Philippine universities in international rankings. Nevertheless, such rankings must be understood in terms of their methodologies, given the fact that they do not necessarily measure the quality of an Atenean education and student formation and do not take into consideration the Ateneo’s own vision of itself.

In fact, Rodriguez believes that the Western biases and premises of the rankings challenge the Ateneo’s rootedness in Filipino rationality. “The only way you can rank high there is when you conform to Western standards on how an academic institution should be,” he said. “When you publish, you publish in Western journals that adhere greatly to the standards of Western scientific knowledge. So, for example, if you’re a philosopher, you’ll measure the validity of your philosophizing on how near it is to Western thinkers.”

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Eduardo Calasanz, who also teaches with the Philosophy Department, states that the value of a good international standing lies largely in its marketing purposes. “If we have good rankings then chances are there will be more and better students who will come to us, and there will be more funding for our research, among other things,” he explains.

Calasanz adds that although international rankings deserve an amount of attention, it is quite important for the community to “relativize” them. “The purpose of the university is to search for truth, and truth has universal horizons—the broader the horizon, the better in terms of search for truth.”

Nation in globalization

The call for Filipinization in the late ‘60s was primarily sparked by the alleged subservience of the university to colonial interests in the face of gross inequality and injustice suffered by the Filipino masses. It was a turbulent period, but while poverty and injustice are still being perpetuated in the country, the present context wherein the university finds itself is radically different from the situation of the late ‘60s.

The Filipino is now facing immense globalization and has to confront the intensification of transnational relations, the greater diffusion of ideas on a worldwide scale and the opening up of cultural horizons.

For Calasanz, it is important to have a strong national identity in order for internationalization to be authentic. “You have to have a nation to be international about,” he explains. “I don’t think internationalization can be authentic if we don’t have anything original or interesting to contribute in the conversation, and that can only come from who we are specifically.”

Rodriguez echoes the same sentiment regarding the importance and relevance of being Filipino. “We’re into nation-building,” he says. “The only way we can really theorize or push for theories and policies that will guide our nation-building is when we are rooted in the Philippine culture and reality.”

He further explains that while the Ateneo may be producing good leaders for mainstream society, only few may actually be grounded in the conditions of the Philippines. While it is great for the country to have globally competitive graduates with an international edge, for Rodriguez, the school must never lose sense of the importance of truly immersing the students in the rationality of the marginalized.

“Clearly, we produce people with the heart to change Philippine reality, but do they really understand the rationality of the majority?” Rodriguez points out. “How can you lead the people if you’re so separate from them?”

Redefining Filipinization

It seems that the discourse on Filipinization has not come to an end. Perhaps the next part of the narrative begins with its redefinition, or the reconstitution of its framework in response to one of the defining realities of our time: globalization.

“Filipinization is a movement which was rooted at a particular context—the context of the Ateneo in the ‘60s,” says Calasanz. “We had no classes in Filipino back then, and we learned more about foreign geography and history than our own.”

Calasanz adds that Filipinization is not a confined discourse. “In a sense, it is continuing. And it has to be continued in this context of globalization which was not the context of the ‘60s.”

Filipino rationality

For Rodriguez, though, Western development is a dead end and it is unnecessary to conform to it. He argues that the best way to be relevant to the Philippine situation is to be genuinely immersed in the rationality of the marginalized, which comprises majority of the nation, and to truly understand their own conception of development.

“I think that there are really lessons to be learned in the grassroots,” he says. He believes that there is a need to pay more attention to the marginalized and study their situation with respect.

“Understanding the real solutions to nation-building and sustainable development will come from there,” Rodriguez adds. “There’s wisdom there.”