The hallways of the Ateneo echoed with the excitement of discourse.

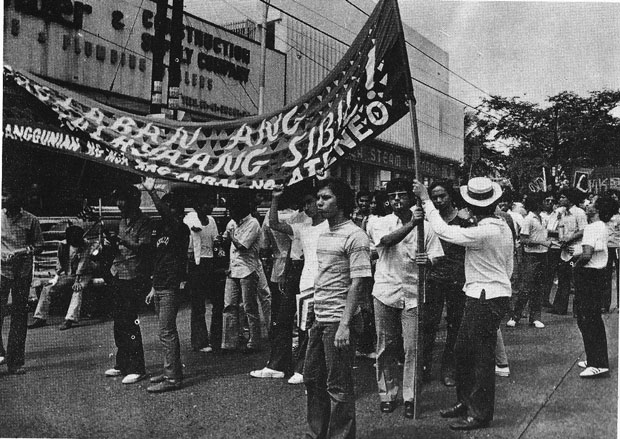

The year was 1968, and the Ateneo student body was involved in discussions surrounding the stirring political turmoil occurring throughout the Marcos era. It was the heyday of Ateneo campus politics, and the whole school was pulsating with talk about principles and ideas concerning social justice and political reform. Most Ateneans then were provoked to engage, taking part in rallies for democratic rule and involving themselves in debates concerning the proper way towards social change.

Thirty years later, the hallways of the Ateneo campus are fraught with discussions of a political nature still. These discussions are of good governance and social entrepreneurship, of service leadership and student council relevance. Yet for discussions concerning the articulation and engagement of ideologies, of clashing frameworks of reality that used to govern student attention and passion thirty years ago, there is only silence.

For any such discourse on the matter has arguably been left at the margins of Atenean thought since then.

Downward trajectory

Ideologies are frameworks of understanding reality. They may be seen as structures by which individuals perceive the world, and through them, reality and its present phenomena can be understood and defined. The method by which each person views the world in turn influences how he or she sees it fit to act; an understanding of the world’s problems provides basis on how to solve such.

According to Arjan Aguirre of the Political Science Department, the concept of ideology became of central importance beginning in the 1960s, when involvement in major political crises necessitated its relevance to student politics and discussions concerning the student body.

The trajectory of ideological debate in the Ateneo, however, has taken a downward turn since the late 1980s, when the turbulence of Philippine politics under the Marcos regime transitioned towards a period of socio-political reform and a focus on economic reparation. For Aguirre, the lack in sustenance of centrality and relevance of ideology in campus politics could be attributed to the students’ decline of interest in national matters, most especially at the turn of the 1980s, when the discourse of peace had ensued.

“There was a huge effort from the affiliated academe to really help the [first] Aquino government restore the nation again, to the extent that there was no longer any cultivated attitude of being critical as well of this very administration,” Aguirre says. “And so the students emulated this behavior. At this point in time, it was not the time to do politics. Instead, [they were thinking], we should govern, manage, and reconstruct, and there was no more sense of contentious engagement and critical analysis of [whether or not] these were really the right means to reform society.”

As less and less student political movements in the 1990s identified themselves with the left, less as well continued to engage in the clash of ideological positions, until no more discussion on political ideologies beyond the classroom setting remained.

A lack of inquiry

For Agustin Rodriguez, chair of the Philosophy Department, the stagnancy of Ateneo student politics is emphasized by its “anti-ideological” character at present.

“Ateneans these days seem to be allergic to ideological discussions,” he says, “and there is no longer any engagement even on the level of being consciously aware of—and cultivating an understanding of—political realities.”

According to Rodriguez, there remains in its place one dominant ideology, one that manifests a liberal democratic nature. The danger, however, lies not so much in the identification of liberal democracy as the dominant framework at present, but more in the fact that this ideology has now become an everyday reality simply left unquestioned and unchallenged by students.

“Take good governance, for instance,” Rodriguez says. “The concept of good governance seems to be a fairly good idea on paper, but if you think about it… we’re actually fitting in with Western rationalities instead of working on our own local modes of development and culture. But no student questions this because everyone these days just assumes it will work.”

Campus clash

Despite criticisms that suggest the lack in articulation and engagement of ideological positions among Ateneans today, there are those among the students that believe in the growing relevance of the political in their lives.

There has been a growing interest once more among student leaders in understanding ideologies and its implications on campus politics. Clashes in campus politics not only revolve around the pronouncement of such ideological beliefs, but also the best means by which such ideologies may respond to social problems.

AJ Elicaño, School of Humanities junior central board (CB) representative and vice president for strategy of the Movement for Ignatian Initiative and Transformative Empowerment, believes that students need to find ways by which their ideological positions may be relevant to the existing campus political system.

“We’re so obsessed sometimes with labeling our ideologies—whether it be Marxist, libertarian, capitalist, social democratic—that we forget the politics of everyday… Politics is everywhere and we need to see the importance of fighting for our own individual ideologies—for what we believe in—in a way that will be relevant to the system,” Elicano argues. “You can’t simply push your own ideology and impose it on others without seeing how it can first apply to the system.”

Bian Villanueva, Secretary-General of the Christian Union for Socialist and Democratic Advancement (Crusada), on the other hand, believes that ideologies do not necessarily have to apply to current systems if the point of such ideologies is precisely to change such.

“I think we can find implicit manifestations of social democracy in our Ateneo classes,” Villanueva points out. “These classes are directed towards making us think… Our values find concretization in articulating an ideology that presents alternatives to what we’re doing now.”

This belief in the importance and relevance of ideological clashes within the Ateneo student body has translated to changing mentalities in the Sanggunian. Alvin Yllana, School of Management junior CB representative and chair of the Alliance of Student Leaders, believes that this gradual transformation in campus politics is something to be celebrated.

“I am happy that politics is growing in Ateneo, that more and more people are taking clearer stances when it comes to their respective ideologies. Mainly it’s because these all help push each student group, political party or coalition, to question if they really believe in the ideals that they current value or not,” he says. “So in that sense, it pushes everyone in the Sanggunian to do better, to take politics more seriously and to identify their own principles for themselves.”

Meanwhile, for Ian Agatep, Secretary-General of the Sanggunian and co-founder of the League of Atenean Youth for Liberal Advocacy, student ideologies must still be grounded and pragmatically manifested in action. Agatep believes that such ideologies must encourage participation, creating movements that may bring students and their potentials together.

However, Agatep adds, “Regardless of where you position yourself in the ideological spectrum, we should be happy that people are even starting to talk about it, that students are increasing their vocabulary and understanding of these different ideas.”

A different frame of mind

Presently, Ateneans have learned to become more conscious of the world beyond the Ateneo. With the possibility of greater socio-political awareness among the students, the question then is: is ideological engagement still a necessary component of students’ lives?

Rodriguez argues that it still is. “The status quo in student politics is not yet enough… Student ideologies are the seabed for real-life skills. It all starts there: if you have a bunch of students engaged in ideology-based politics, instead of complacently and comfortably just going with what they’re already used to in status quo, we can then start to properly theorize about society and the solutions to its deep-seated problems.”

He adds, “It’s sad that the problem is not that students are apathetic—a lot of them actually do want to change the world. The problem is that they all change the world in ways that they are sure already work, without asking if these are necessarily right.”

He says, “We need more students who are aware, more students who have frameworks of understanding reality, and in turn [more of those] who actually think and question.”