The word “innovation” often calls to mind images of jetpacks and scientists tinkering with robots. However, it may be closer to home than we think. It begins in an unassuming room on the second floor of Faura Hall—the operations office of the Ateneo Innovation Center (AIC). In ways both ingenious and unconventional, the AIC takes us deeper into the heart of advancement, something we as a Filipino people have yet to fully dive into

Bringing it together

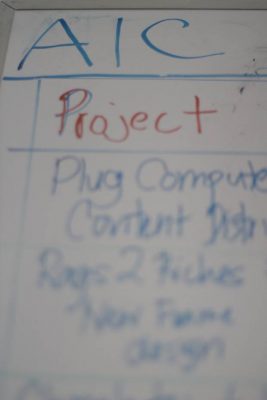

In this room, the AIC takes research a step further, allowing its interns and volunteers to build, create and develop their skills outside the classroom. A ceiling-high whiteboard stands in their office, filled with notes of projects being handled by students of all year levels.

Mind you, one doesn’t need to be from the School of Science and Engineering to get involved. The AIC’s interns come from a wide variety of courses—from computer engineering to fine arts, from communication to philosophy. Innovation, after all, is usually the product of different interests coming together to share ideas. In the AIC, each field is important, be it software programming, aesthetic design or product development.

Ironically, the center seems to work primarily under the radar. “We’re more outside than inside. That’s why most [Ateneans] don’t know that we exist,” jokes AIC Operations Officer Matthew Cua (BS MAC ’06). They have around 360 industry partners, including the Ayala Corporation, Smart Communications and Globe Telecom.

For senior and AIC intern Sam Chan, who is double majoring in information design and management information systems, the center’s large-but-small environment makes working for it so rewarding. “I found creativity and energy in a multidisciplinary way. I met many kinds of people. It’s about expanding horizons.”

Sometimes, the chance to expand one’s horizons is genuinely actualized. The AIC engineers once collaborated with eco-ethical design company Rags2Riches and Artillery, the Information Design home organization, to create environment-friendly lighting fixtures out of paper and low-energy LED lights. When a representative from Starbucks saw the paper chandelier a student had created, the designer was hired on the spot.

Cua explains in a mix of English and Filipino, “The programs are capacity-building enablers. Even if you’re just a freshman, you [can help] build hovercrafts and underwater cameras.”

Reinventing invention

The AIC isn’t your stereotypical academic center, with a rigid hierarchy and stuffy formalities. In this flexible, non-bureaucratic environment, the AIC’s unassuming band of young scientists work together to make creative solutions to problems many take for granted.

Driven by what Chan calls a “collective energy,” AIC’s members take projects on an initiative basis, with each small group working on their own pet projects. It’s easy to be reminded of the television series Big Bang Theory and its protagonists’ random experiments.

Taking inspiration from the movie Up, the AIC once tried to find out how many helium balloons it would take to fly a camera. (The answer, as they discovered, is 110.) Another time, they put sound recorders inside ice cream cans and placed them around campus to measure rainfall—the stronger the rain is, the louder the sound. “If you see random ice cream cans around campus, don’t kick them!” jokes Cua.

While such methods may at first seem kooky and unscientific, the AIC’s research gets real results. For example, they hacked a Kinect, a motion-sensing controller for the Xbox 360, to provide at-home rehab for stroke victims. It just goes to show that in research, purpose and fun can go hand in hand.

Proactive progress

Mere decades ago, the Philippines was the richest Southeast Asian country. Today, big plants like FedEx and Intel are packing up and leaving for Vietnam, taking tens of thousands of jobs with them as they go.

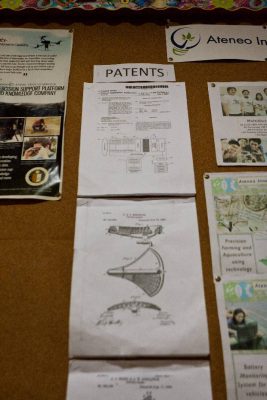

These days, global competitiveness is tied to innovation—the ability to create something nobody else has. Thus, innovation can be seen as steps toward bridging the gap between the Philippines and other countries.

At the same time, the AIC targets the Philippines’ technological pitfalls by focusing on the following, with the hope of first improving Filipino lives: disaster science, green technologies and biomedicine.

For example, the AIC studied how to make rainwater drinkable to benefit flood victims and how to use old refrigerator parts to build much-needed baby incubators for public hospitals. Their studies in algae—a valuable product in pharmaceuticals, biofuel and even cosmetics—are part of the reason why the Ateneo is one of the county’s top universities in algae research.

Within the Ateneo, the AIC’s impact can be seen in the fact that the AIC has successfully turned the Matteo Ricci Study Hall into the first zero water waste building in the university. Outside its immediate community, the AIC is also involved in environmental technology.

For the fisherfolk of Sarangani Bay, where some have the job of manually counting millions of tiny fingerlings a day, the AIC invented a digital fish counter. And while most dismiss fishkills either as an unavoidable fact of life or as a result of supernatural phenomena, the AIC has zeroed in on Lake Palakpakin after 800 tons of fish died there a few months ago. Their goal? To rehabilitate the lake, find solutions to fishkills and prove that something can be done to make things better.

Making things matter

The Philippines has yet to fully embrace a culture of innovation. For example, UP Diliman’s TechnoHub was envisioned to be a center for technological advancement, but has instead become more known for the restaurants found in its grounds.

Whether in terms of global competitiveness or changing local communities, the Philippines has a long way to go. Cua describes the challenge before the AIC: “We’re tasked to break boxes and ask difficult questions. Can students learn outside the curriculum? Can we get the Philippines up from last place to first place?”

With the AIC working as a quiet force of ingenuity, we see that whatever methods are used and whoever is involved in it, innovation needs no fanfare. Change speaks for itself.

With reports from Alex P. Santiago and Apa M. Agbayani

- Photo by Paolo Maddela

- Photo by Paolo Maddela

- Photo by Ryan Racca

- Photo by Ryan Racca

- Photo by Ryan Racca

- Photo by Ryan Racca

- Photo by Ryan Racca

- Photo by Ryan Racca