“Buti naisingit pa kayo,” Flor Sanchez, the secretary, says, smiling sparingly from behind her desk. The waiting room is quiet and only silence echoes from the corridors. After all, hardly anyone in the Ateneo knows where the Höffner Building is. Even less would expect that Fr. Bienvenido Nebres, SJ has now holed up here.

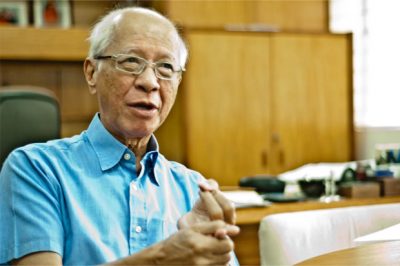

The mess in the waiting room, and even in the office itself, would be disorienting to anyone expecting more impressive headquarters for the former university president. The place is riddled with piles of random implements that have long lost their value, left behind by the former occupants now relocated at the Faber Hall.

But when the occupant of such an office is as busy and cosmopolitan as Nebres, even the mess would begin to make a lot more sense; he is always either in deep thought or on the move, and he barely has time for such trivialities.

In fact, during The GUIDON’s interview with the Jesuit last November 12, he just got back from Guangzhou for an engagement with the Ateneo’s partners in Sun Yat-sen University. Two days later, Nebres would once again be headed out of the country, this time to participate in the World Science Forum in Budapest.

It is easy to see where Ms. Sanchez was coming from.

Past to present

But it was actually Nebres’ choice to stay in the office, at least until a more permanent arrangement is in place. The former president, who is currently on sabbatical leave, holds no new official appointments just yet, and likes to spend his time writing in the silence of the secluded building.

After all, silence is something that, one would surmise, Nebres never got complete hold of for more than 40 years, since he began holding key positions and making a lot of impact in the Ateneo and beyond.

A Stanford-educated mathematician, Nebres was appointed dean of what used to be called the College of Arts and Sciences back in 1973, during the heyday of the Marcos dictatorship.

Nebres later on served as the Provincial Superior of the Philippine Jesuits. Finally, after a brief stint as president of Xavier University in Cagayan de Oro City, he was appointed president of the Ateneo de Manila University in 1993, succeeding another distinguished Jesuit, Fr. Joaquin Bernas, SJ.

Nebres would remain president for a record 18 years.

A globalizing word

Nebres’ frequent trips abroad testify to a reality that he had to confront during his assumption of the presidency: the age of globalization.

“The mission of the Ateneo has always been the same—academic excellence, service, and helping build the nation—but the context changes,” he says. “When I was dean in the college, the context was martial law. In the 1990s, the context was globalization.”

Indeed, how the rest of his regime would unfold seems to have been defined by this initial understanding of the context of the times. Nebres identified two things as necessary to respond to the reality of globalization: addressing the competitiveness gap between the Philippines and the rest of the world, and addressing the poverty gap between rich and poor.

“To understand this competitiveness gap is to really understand that we live in the most dynamic region in the world,” Nebres explains. “The countries around us are the most competitive in the world: China, Singapore, Vietnam, Korea, and so on.” In this regard, Nebres pursued efforts to benchmark against these countries, especially in education.

The Ateneo benefited a lot from this drive for competitiveness. This is especially apparent in the university’s improvements in infrastructure and research.

Equally important, however, are Nebres’ efforts to close the widening poverty gap brought about by globalization.

“The other part of what’s happening in globalization is that it is actually increasing the gap between rich and poor,” Nebres explains. “If you look at the Philippines today, many of the rich are actually much richer, but the poor are also much poorer.”

It is Nebres’ particular approach to this second challenge that has met a lot of criticism in some circles.

Hands-on work

Addressing questions regarding the shift in his leadership style over the decades, Nebres says that this is a result of the changing times.

“In the 1970s, we were very focused with getting out of martial law. In that context, the leadership style required a lot more of advocacy and confrontation,” he says. “[But] while our immediate goal at that time was to get out of martial law, we also knew that that was not the main goal. The ultimate goal was really to close the gap between rich and poor, and to really improve the lives of the majority of our people.”

Nebres says that by the 1990s, what struck him and other observers was that the country was not making much progress on poverty, despite the overthrow of the dictatorship. “In fact, [poverty rates] either remained the same or actually got worse. And so, there was a need then to find ways of leading that would make a better difference on poverty,” he says. “In terms of style, I [became] much more concerned on finding things that work—in a sense, more pragmatic.”

The Millennium Development Goals served as the concrete objectives that Nebres took into consideration at the time. “In 1990, the developing countries signed the Millennium Development Goals… The first Millennium Development Goal is to cut in half extreme poverty and hunger between 1990 and 2015. Number two is universal primary education,” he says.

“We are not going to achieve them. We had around 40% [poverty] in 1990; we’re still at around 34%. We are the one, major country in Southeast Asia that will not meet the first Millennium Development Goal,” Nebres explains. “And, on the second Millennium Development Goal, which is universal primary education, there’s no way. Of every 2.4 million children who enter grade one, at least 800,000 never finish grade school.”

“When looking at that data… we realize that macro solutions—trying to solve [problems] by changing the president, or by lobbying against congress—are not going to work,” he says. “And so, we began to look at things that were on the ground. We found, for example, that Gawad Kalinga (GK) was quite effective in building communities.”

This pragmatic approach meant that the Ateneo, as an institution, would deliberately distance itself from contentious politics throughout the Nebres presidency.

No politics

But for Lisandro Claudio, PhD, a lecturer with the Political Science Department, Nebres’ avoidance of contentious politics—what the former university president called macro solutions—is problematic. Claudio believes that the methods Nebres prefers for addressing social ills are hardly sufficient in combatting problems such as poverty.

According to new university president, Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin, SJ, Nebres “put a stress on the regional and local domains, because that’s where you see results. There is a certain difficulty and complexity working at the national and the global.”

Claudio does not agree with this approach, which includes the university’s collaboration with Gawad Kalinga. “There’s a problem with making it seem as if the solutions to poverty are immediate, visible, tangible, stopgap solutions, like GK,” he says.

“You need to address contentious political issues. For example, you might have built a GK house for someone, but then the parents [might not] have stable employment. What’s the solution there?” Claudio says. “One of the solutions is to campaign for a security of tenure bill in the House of Representatives, which entails actually going against vested interests—getting into trouble.”

Going with what works

“Every time Fr. Ben and I engaged each other in public fora, I was always, in a sense, finding myself contradicting him,” says Agustin Rodriguez, PhD, a poverty researcher and chair of the Philosophy Department. “He didn’t like people getting too much into policy debate, I think. [Fr. Ben would say,] ‘Tama na ‘yang mga policy research, policy debate na ‘yan. Get into the action.’”

“He’s really a pragmatist, and that really left a strong legacy in Ateneo,” Rodriguez says. “But I really disagree with that approach.”

“When he says let’s not do policy research, and let’s just go with ‘what works,’ and let’s not think ideology, [that just won’t do],” he says. “[Because] if you’re just always doing ‘what works,’ [then] ‘what works’ is capitalism, and look what it’s doing to our environment, look what it’s doing to the labor force.”

“If you don’t have a position—not necessarily an ideological position, but at least a position that comes from some theoretical reflection on what ought and ought not to be—and sige ka na lang nang sige, we’ll just regret it when we’re already caught in a system that’s not humane, for instance,” Rodriguez explains. “I really think that pragmatism will lead us to perdition.”

Fresh debate

Nebres’ sense of temporality seems to be a lot more heightened compared to other people. Where others would see a continuous, linear history, the old Jesuit sees more the breaks that distinguish one period of history from another. This seems to beget his conviction that changing times call for new approaches.

“In the 1970s, 1980s, I used to run political seminars on different forms of social democracy and different forms of democratic socialism. However, as I said, that was in the time when ideologies were very dominant,” he says. “If you look at what is driving our world today, there are no great ideologies anymore. They’re gone.”

Rodriguez and Claudio are only two of the Ateneo faculty members and students who would find issue with Nebres’ pessimistic attitude towards the theoretical disciplines. After all, the Ateneo has a historical bent towards the humanities and a strong appreciation for the social sciences.

But if there’s anything Nebres’ focus on “what works” has done for academics like Rodriguez and Claudio, it’s to provide a new opportunity for fresh and sustained dialogue on what really does work for a country like the Philippines.

With reports from Steffi C. Sales

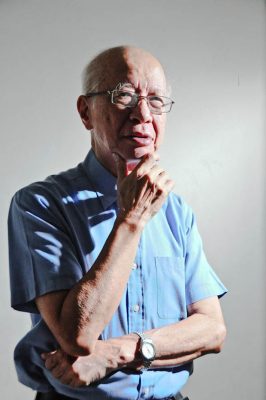

- Photo by Migi C. Soriano

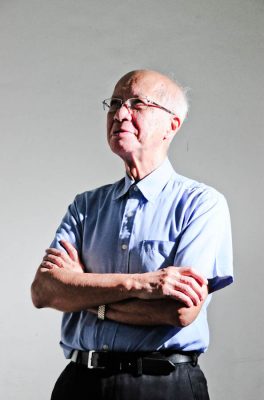

- Photo by Migi C. Soriano