Carlotta*, an Atenean, was only 15 years old when she met a man online and decided to go on an “eyeball” with him. Despite the dangers the blind date augured, it proved to be an amusing night of getting to know each other, and later culminated in a decision to meet up again.

Their second date involved more than a dinner and a conversation—afterwards they checked into a nearby motel to have sex.

In the years that followed, Carlotta has had sexual relations with various men, ranging from chance acquaintances to partners from her own circle. Her policy when it comes to sex with strangers? Never sleep with the same person twice.

And while other people prefer to have sex in the confines of a private room, she claims to have done it in public, including the Loyola School of Theology roof deck and the washroom in Cantina. Moreover, she says that she doesn’t like using condoms. “You just [won’t] like the [feeling of protection]. I deliberately ask the person to stop.”

Carlotta is part of a small number of Ateneans who hold an extremely liberal sexual outlook not shared by most of their peers. Despite all sorts of discouraging factors, sexual behavior at university-level academic institutions is a seemingly unavoidable occurrence.

A path of peril

There are those like Randy*, who admitted to having had intercourse with a prostitute once. “Love and lust are entirely separate,” he explains. Still, he says, “It’s cheesy, but I do believe that sex should be done in love. It just doesn’t mean that every sexual activity should involve it.”

According to Andrea Soco, faculty member of the Sociology and Anthropology Department, “any [kind of sex] that is premarital is a form of deviance, and thus would be risky.” Deviance, in the sociological sense, refers to actions that go against the prevailing norms of society.

Soco’s definition of premarital sex would mean that both Carlotta’s and Randy’s cases are considered deviant behaviors, but whether or not these behaviors are acceptable, it is clear that there are considerable risks involved in these practices.

Health Sciences Program director Dr. Norman Marquez explains that casual sex may lead to harmful sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea, syphilis, and even HIV/AIDS. Moreover, he says that the effects don’t just include physical discomfort and an expensive treatment; the individuals who engage in it might need to confront psychological and moral issues as well.

But perhaps it never quite comes to a head until it gets as serious as a teenage pregnancy.

There have in fact been some whose fears of impregnation had transformed to reality. Anne* says that she used to only rely on pills, since she trusted that her long-term boyfriend could effectively pull off the withdrawal method. That is, until the moment she began exhibiting symptoms of pregnancy.

She eventually took a pregnancy test, and her worries were confirmed when it turned out positive.

Right now, she is still going to school, even while carrying a child to term. “Kahit sabihin mong blessing [‘yung bata], sayang pa rin. It shouldn’t have happened now,” she says, explaining that she still has to finish her studies. She mentions that her doubts and frustrations had led her to think about abortion.

Batting for the same team

The three cases presented paint only the struggles faced by young straight men and women. However, as attitudes toward sexuality become increasingly open-minded, it is also equally important to consider the health and well being of variant sexualities.

Take the case of Jack* and Tyler*, for example. The two usually have sex once a week. They’re commonly seen publicly displaying affection on campus, and in parties, they have no problem cuddling and making out in front of other people.

“I don’t see anything wrong with [public display of affection],” Jack, a senior, says. “It’s not really offensive; it shouldn’t be.” For his part, Tyler, a sophomore, says, “I’ve been struggling [in the closet], and I’m done with [that] now. I just don’t [care] about what other people say.”

Nevertheless, Jack and Tyler are both fully aware of the dangers of sexually transmitted infections, and with this awareness came their decision to both get tested for them—something that Carlotta and Randy could perhaps learn from the two.

Fortunately, both of Jack’s and Tyler’s tests turned out to be negative.

Monica Jalandoni, a faculty member of the Theology Department, holds an unconventional view of homosexual acts. She says, “I don’t believe homosexual acts are inherently wrong, if [homosexuals do] it in the context of a stable, loving, relationship.”

Her views contrast with the official Church teaching on homosexual acts, which says, “under no circumstances can they be approved.”

Soco explains that deviant sexual behaviors spring from an individual’s upbringing and socialization. In the case of sexual minorities, though, she says that they engage in non-normative sexual behavior “because that’s how [they] express [their] sexual orientation. What’s the point of this sexual orientation if [they’re] not going to express it in some way, or externalize it?”

This is where sexual minorities sometimes feel that they are being unfairly dealt with. Jack, for example, objects to the Roman Catholic perspective that says homosexuality is okay, but homosexual acts are wrong. “You can be gay, but you can’t do anything [about it]!” he says. “It’s extremely ignorant of them to say [that]. Have they ever been gay?

Reason and responsibility

Jalandoni thinks that a the problem comes when people are already put in danger by the sexual act, such as by risky sexual behavior. “It’s disordered love—they’re trying to express their love, but they’ve lost understanding of how to connect sex to it,” says Jalandoni.

Fr. Adolfo Dacanay, SJ, Theology Department chair, argues that people should have sex only in the context of marriage. “Sex is a language… What you are saying [to your partner] is that I am [not just] erotically attracted to you,” he says, “but I’m [also] saying I love you, I care for you, and I’m responsible for you for the rest of my life.”

On the other hand, social sciences senior Angelica Mangahas, former president of the Ateneo Debate Society, refuses to give a moral generalization. She says, “As long as there’s consent, as long as there’s no harm, and as long as everyone comes out of it happy, then surely, the world hasn’t been left off a worse place from that decision [to have sex].”

“[Saying that sex is for intimacy] is very arbitrary… You can choose more things for intimacy that are appropriate for you,” she explains. However, Mangahas draws the line at the point where someone might get hurt: “It is okay to have sex, but it is not okay to have unprotected sex.”

On the side of caution

For Dacanay, the whole matter can be seen as a question of character.

“I think the whole idea should be that we form our values properly, adequately,” he explains. “We [should] know that [sex] is a language, so that we do not disrespect the other person.”

While Dr. Marquez of the Health Sciences Program doesn’t necessarily approve of casual sex, he says that there should be sex education for all. It is in this regard that he echoes Dacanay, at least in the way he puts a premium on proper education and formation. “It has been part of my job to be able to help my students consider many things before they engage in risky behavior—whether it be taking drugs, gambling, or having casual sex,” Marquez says.

Rory Catipon, a guidance counselor from the Loyola Schools Guidance Office, says that while the need and curiosity for sex is natural during puberty, institutions such as the family, school, and religion should be responsible for the formation of an individual’s sexual outlook. “The ideal response is to take action to consistently and constantly provide as much support as we can,” she says, explaining how one should deal with a friend who is dealing with sexual control issues.

The topic of sex will always inherently be a topic that brings discomfort when discussed publicly. At a university level, faint chuckles can still be heard when sexual topics or points of digression arise within academic discussions. In the Philippines, the statistics of the prevalence of HIV/AIDS may not be as alarming as those in Africa, but that does not mean that risky sexual behavior should be ignored.

As Marquez puts it: “Better safe than sorry.”

*Editor’s note: Name has been changed to protect the individual

Updated October 20, 2011, 9:55 PM.

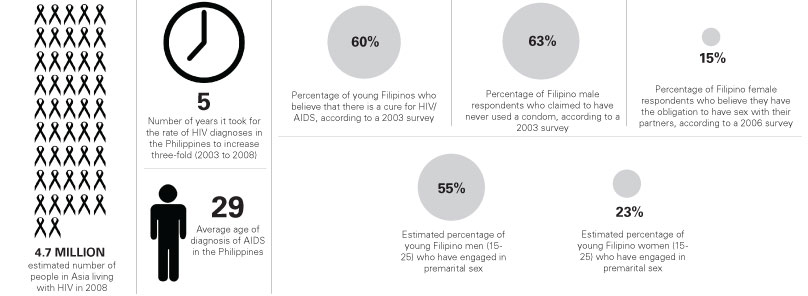

AIDS by the Numbers

Changing social attitudes towards sex point to both increasingly liberal outlooks and continuing misconceptions.

Data fromUNAIDS, Journal of the International AIDS Society, Philippine HIV and AIDS Registry, Asia-Pacific Population and Policy, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health, Japan Center for International Exchange and the Health Action Information Network.