With the tagline “See the Unseen,” this year’s Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival promises to be an exciting showcase of the work of independent Filipino filmmakers. Set to run from July 15 to 24, the films in contention are a diverse collection of astute social commentaries, thought-provoking comedies and powerful dramas.

Among these films are works by Atenean filmmakers from all over the country. Ramadan, which won the award for Best Communication Thesis in the Loyola Schools last year, is showing as part of the festival’s Best Shorts program. Meanwhile, the film Un Diutay Mundo by Ateneo de Zamboanga’s Ana Carlyn V. Lim is in the competition proper, going up against the entries of local greats in the country’s biggest showcase of independent film.

We sat down with two directors participating in the festivities from our own university: a fresh graduate and a seasoned filmmaker.

“Is it okay if I get some coffee first?” a blasé and laidback Gio Puyat greets us, pointing to his black Star Wars tumbler. Just a few minutes into the interview, though, the serious and passionate storyteller in him shines through. Between sips from his tumbler, Puyat casually talks about his aspirations and early experiences in the film industry. This AB Communication fresh grad’s short film, Immanuel, revolves around a family struggling to survive in a dystopian Philippine setting where oxygen is a scarce resource. The film was made as an undergraduate thesis project with two other Ateneans, Gracie Vergara and Janeil Tibayan.

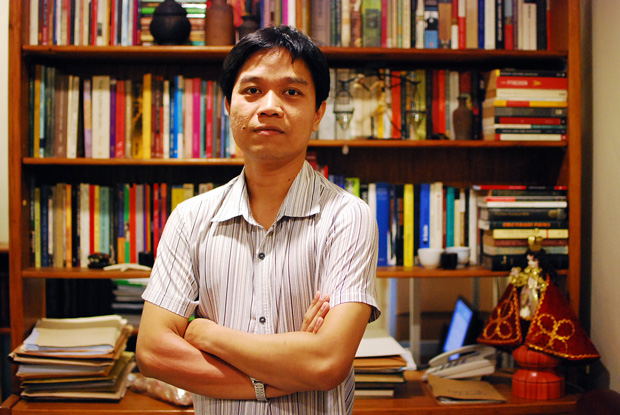

Later, we enter Alvin Yapan’s office at the Filipino Department, where he greets us cheerfully and asks for each of our names. Once we’re acquainted, he regales us with amusing and insightful stories about film, art and the day-to-day disasters in the life of a Filipino director. Initially gaining recognition for his Palanca Award-winning work`s as a fictionist, Yapan’s first two films were critically acclaimed and won him a number of awards. His new film, Ang Sayaw ng Dalawang Kaliwang Paa, explores the convergence of sexuality, poetry and dance. He chose poems by feminist writers such as Joi Barrios, Benilda Santos, Merlinda Bobis and the late Ophelia Dimalanta, who willingly waived their poems’ copyright fees for use in the film. Each poem was set to music, which was then further complemented with choreography.

Puyat and Yapan, though both enthusiastic about their craft, have different perspectives about the film industry. Filled with wide-eyed excitement, Puyat looks forward to getting more exposure because of Cinemalaya and jumpstarting his filmmaking career. Yapan is a bit wearier and wiser, stressed over his film’s post-production and fully aware of the industry’s inherent problems.

What definitely binds them, though, is their shared passion for film and professed love for the industry. To them, festivals like Cinemalaya are important because, as Yapan says, they “infuse new blood into our ailing Philippine film [scene].”

This is the task for young directors and experienced luminaries alike: to breathe new life into Filipino film, and to make the audience see the unseen.

What inspired you to make your Cinemalaya entry?

Gio Puyat: At the time, I was reading 1984 by George Orwell and the graphic novel, V For Vendetta—it was a time when I was reading a lot of sci-fi. That was one of the reasons why [the idea of a dystopian film] came up.

Alvin Yapan: I really wanted to make Filipino poetry accessible to the mass audience because almost all literary adaptations that we have in Philippine film come from fiction, but rarely—baka nga wala—[do they] come from poetry.

What are some challenges you’ve had to overcome in filmmaking?

GP: Every time we shoot, it’s a challenge. It’s like Murphy’s Law: everything that can go wrong will go wrong. That happens every time in production.

AY: Stress level, kapatid. Sometimes, it’s really a mystery how after everything, you can come up with a sane film in this country—because it’s really crazy.

Cinemalaya’s tagline this year is “See the Unseen.” What “unseen” things does your entry reveal?

GP: It’s really about the social divide and how it affects society. I guess when you say “see the unseen,” [my film is] not just a sci-fi movie about a family who has to fight for their oxygen—it’s [about] what happens now. We just put a different context into [the film] but it’s the same kind of divide. People are still suffering, people still get eaten by the system and they have no control over it.

AY: I filtered the poems through the eyes of two male characters so [there’s a slight] bromance/gay angle, [but we didn’t want to market it as a] gay [film]. I really want this film to be a statement against the backlash at independent cinema, which says [that we indie filmmakers] always focus on issues of poverty and homosexuality just to sell ourselves. We can still tackle lesbian/gay issues [and] feminist issues without resorting to sex.

I also wanted to feature in my film how Filipino artists would try to survive in a Third World setting. At the same time, ayoko ng über-serious: [a work screaming] “We’re so oppressed!” [I want there to be] dignity in the way we tackle the Third World condition, [but] I still want it to be accessible. I want the audience to enjoy Filipino film again.

What rewarding experiences have you had making films?

GP: I love screening my films! The point when you start to reap the benefits of your work is when you’re screening it for the first time in front of an audience.

AY: [Long pause.] Is there a reward? So far financially, wala. [He laughs.] Maybe the reward is seeing your work screened in front of an audience. You feel like an orchestra conductor, as in “O, dito tatawa na kayo! Tawa!” or, “O, dito matatakot na kayo! To the left!” It’s fulfilling—and you cannot buy that.