More than two years ago, Richard Brodett, Jorge Joseph and Joseph Tecson, all scions of rich families, were arrested on drug trafficking charges by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) in a buy-bust operation. Dubbed as the ‘Alabang Boys,’ the trio drew public attention not only for selling drugs in upscale places, but also for coming from a well-known educational institution, the De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde (CSB).

Since then, colleges and universities have heightened their anti-drug campaigns. By a lot of indicators, though, it seems that the fringe phenomenon of drug use is still as much an accepted part of university culture as it was before, including in the Ateneo.

Amidst the hustle and bustle of busy school days, senior Pancho* makes it a point to satisfy his frequent urge to get high. He drives out of school and looks for a quaint parking spot among the many restaurants that line Katipunan. With doors closed and the air-conditioning turned on, he lights what seems to be a peculiarly shaped cigarette—a rolled-up sheet of paper stuffed with dried marijuana leaves.

Euphoric sanctuary

Pancho is emboldened by the fact that he has never been caught. Describing himself as a “closet drug-user,” Pancho has been using prohibited drugs since his sophomore year to cope with academic pressure.

“It relaxes me,” says Pancho. “Some students have videogames, some play sports, and some of them drink. [Marijuana] is my way of [managing] stress.”

Pancho’s first encounter with pot did not happen by chance. He got acquainted to it after opening up to a friend about his failing marks.

“At that point, I was willing to do anything [because] I felt like my whole life was collapsing on me. My friend [from another university] said it would calm my nerves. It worked,” he says.

Since then, the relationship between Pancho and the drug flourished.

“It was as if [marijuana] opened a whole new chapter in my life,” he says. “Now, I am graduating this March.”

Moreover, he does not think that drugs destroy one’s life, mentioning that even American President Barack Obama has admitted to having used marijuana and cocaine in his youth.

“If you look at him now, [Obama] is the most powerful man in the world,” he adds.

One of the crowd

Pancho’s situation mirrors that of many young Filipinos. PDEA reports that the number of young drug users in the country has increased by as much as 313% within a span of three years (2007-2010).

In a separate tally presented by the Dangerous Drugs Abuse Prevention and Treatment Program of the Department of Health, the 4,000 drug cases admitted to different rehabilitation centers in 2006 ballooned to almost 16,000 in 2009—not yet including unreported cases.

Moreover, both reports mentioned two notable trends. First, around 60% of the cases were reported in urban areas, specifically Metro Manila. Second, almost 30% of the reported cases were of high school students.

PDEA Director General Dionisio Santiago laments that substance abuse will always be a problem with the country’s youth.

“It is the youth who are our [country’s] biggest users,” he says.

Associate Dean for Student Affairs (ADSA) Rene San Andres believes that the problem lies in the youth’s struggle for identity and for adjustment in the adult world. He says that “SAD”—sex, alcohol and drugs—particularly entice hormonally charged youngsters, three things that for him make a volatile mix in life.

Druggie deterrents

In the Loyola Schools (LS) today, the only thing that stands between Ateneans and drug use is the random drug testing.

Mandated by Section 36 of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 (RA 9165), the program requires arbitrarily selected students to provide urine samples to the Loyola Schools Office of Health Services (LSHS), under the supervision and guidance of qualified personnel. The system has been in place since late 2007.

Universities in the country, including CSB, have been implementing similar systems.

San Andres believes that the current system has been doing well enough. “It’s working. People are getting caught,” he says. “The results we have are well within the national average.”

For John Paul Vergara, Vice President for the LS, this is a major advancement for the Ateneo. He says the school did not have a strong anti-drug policy back in his time during the ‘80s.

“I don’t remember any kind of drug testing during our time,” he says. “You would [only] get caught if they saw you [actually using drugs].”

Vergara adds that while he had heard cases of drug use by other students then, he could not recall somebody being sanctioned or even caught.

Meanwhile, the Ateneo has been very meticulous with its current drug policy. It has even gone so far as to allocate nine pages of excerpts from RA 9165 in the Student Handbook.

‘I don’t worry’

Even with the tightening school policies on drug use, Pancho does not seem to fear being caught. “I don’t worry about [the random drug testing],” he says. “It’s at the back of my mind.”

He even feels brave enough to smoke pot during school days.

“Sometimes, I would just skip lunch,” he says. “There have been times when I would come to class high, and no one would notice. If I get too high, I would just cut class altogether.”

He says he follows certain measures to ward off suspicion.

Pancho sprays his car with scented aerosol after a fix. In addition, he brings with him an extra set of clothes that he would put on after taking a bath in the covered courts. He would also gargle with mouthwash in one of the university’s many restrooms.

Moreover, Pancho has a “safe” storage for his stash. “It’s safely kept inside my locker. The guards don’t check it anyway.”

“There aren’t any risks involved,” he says. “I’ve been doing this for years and I’ve never been caught.”

Reach of the radar

Playing it safe, Pancho says that he remains untraceable to the radar of school authorities by never using drugs inside the campus.

Expectedly, drug use among Ateneans does seem to happen a lot more outside school, presumably for the same reasons as Pancho’s. In an article in The GUIDON article entitled “Party ‘Til You Drop” dated September 2008, parties handled by student organizations were reported to be vulnerable to drug peddlers, some of whom are just university students.

San Andres said in the article that the rules of the university still apply to such parties because school organizations carry the name of Ateneo. Thus, proven perpetrators are still sanctioned accordingly.

Punishment is secondary

According to Vergara, the Ateneo follows the law on drugs “conscientiously.”

“We don’t just comply with it,” he says. “We see what’s realistic in our setting and see how we can [include] a formative aspect in it.”

True enough, the school’s current anti-drug campaign puts a greater premium on formation than on prosecution.

Unlike other disciplinary cases, random drug testing works as a ‘strike’ system. Upon failing a drug test for the first time (strike one), the concerned student is not prosecuted immediately. He or she is not yet reported to the ADSA.

Instead, the student undergoes a rehabilitation program. He or she is constantly monitored and would have to go through regular drug testing. It is only upon the failure of the second test when the ADSA comes in for prosecution, and it is only during the third strike when the student becomes liable for expulsion.

“We give you a chance to fix yourself,” San Andres explains. “Some people just need a rap on the head.”

San Andres believes that punishment is secondary when it comes to the school’s anti-drug policy.

Vergara agrees. “The framework we use is not punitive justice; it is restorative justice,” he says.

Vergara explains that the former is concerned solely with punishing individuals who committed a crime. However, the Ateneo desires “to mainstream” these individuals again.

“The point behind restorative justice is that the violation is a diversion from the main path,” he says. “It’s how we ensure that the individual will graduate according to the vision of Ateneo de Manila.”

Vergara also believes, though, that the task of guiding drug users back to the ‘clean life’ is a communal task. Thus, the university does not rely on random drug testing alone.

“We need more responsible students; [those] conscientious enough to report [drug users],” he says.

At the very least, while occasional drug use among college students is relatively commonplace—being a recognized if not accepted fact among many Ateneans—there is still wide expectation that the system in place will successfully deter any group potentially called the Loyola Boys from hitting the black market soon.

*Name has been withheld upon request.

Checking into rehab

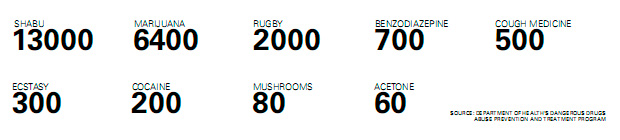

The number of patients admitted to drug rehabilitation programs in the country numbered at around 16,000 in 2009. The breakdown of reported drug abuse cases and the involved chemicals are as follows:

hi,

nice information away of drug rehab.thanks for sharing.keep it up.cook info..