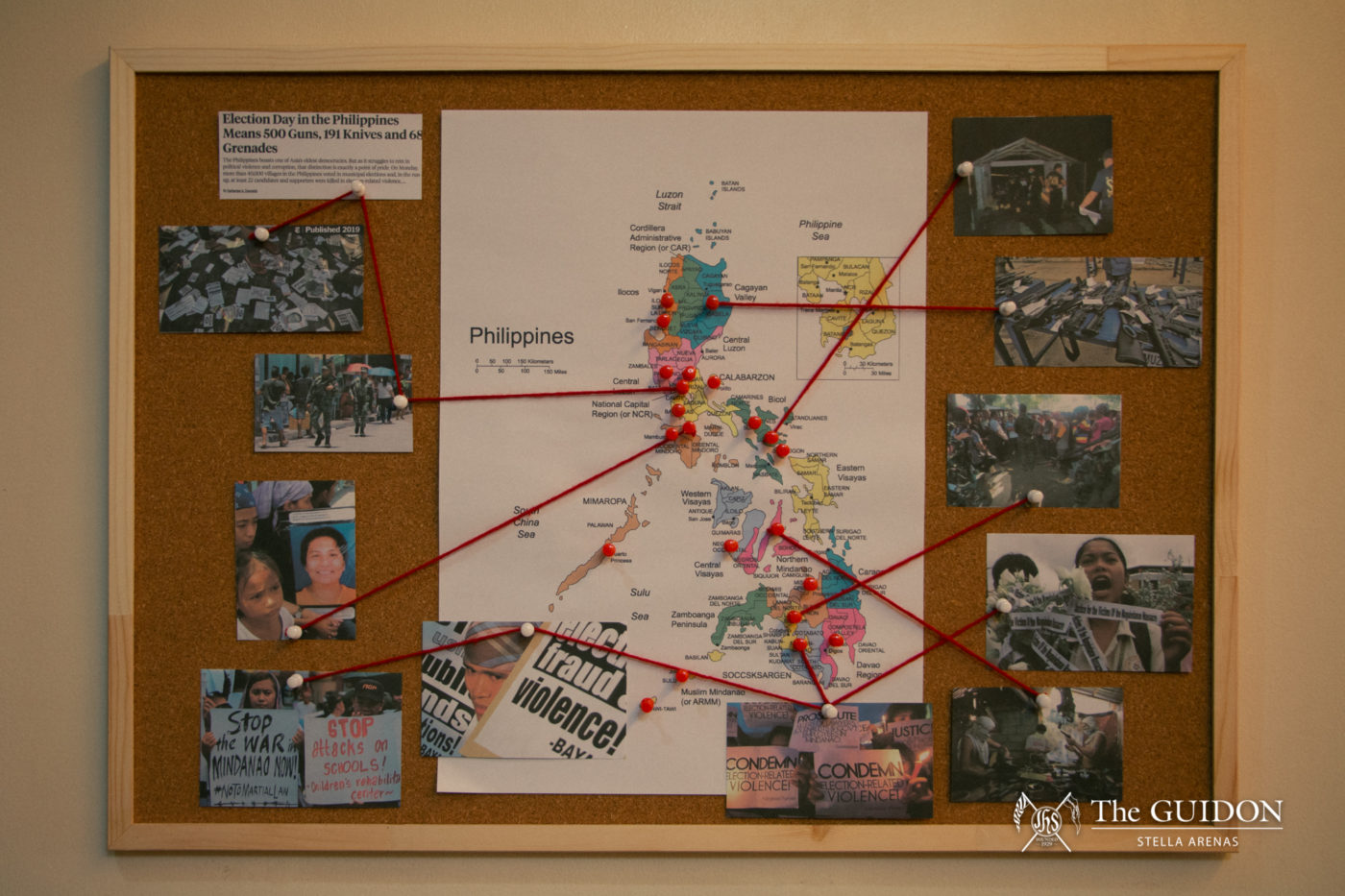

AS THE May polls draw near, so does the likelihood of political violence among the candidates’ adversaries and respective supporters. Numerous instances of these cases, such as the 295 deaths lost during the 2004 elections, serve to characterize the Philippines as a hotspot for politically-motivated violence.

While democratic systems were restored after the creation of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, there remain numerous factors that hinder the Philippines from fully achieving democracy. To escape the recurring pattern of guns, goons, and gold, reinforcing the current justice systems and engaging active stakeholders is crucial.

Uncovering the roots

The implementation of justice systems in election periods was borne out of a need to address the political instability of the years 1965 to 1998. Fighting between non-ideological factions led to the increase of electoral violence cases that devastatingly took 2,000 lives during the 1984 polls.

While the post-EDSA government attempted to achieve stability by reinstating democratic structures, a large number of political candidates turned to personality politics. Rather than focusing on a candidate’s platform, the general public was more invested in a candidate’s overall personality.

Taking advantage of the public’s mindset, candidates attempted to attract voters by offering rewards, which transformed Philippine politics into a coalitional pyramid. The government’s systems simultaneously failed in propagating democracy and instead monopolized electoral violence instead. Numerous sectors took advantage of this weakness, as seen in how political dynasties organized private armies for their personal agenda.

A prime example of this is the Ampatuan Massacre, which involved the murder of 58 people, including journalists, witnesses, and those in an opposition candidate’s convoy. Even after Andal Ampatuan Sr. and his private army were charged, there was no move to revoke Executive Order 546, which allowed the private armies’ existence. To simultaneously protest and raise awareness on cases of electoral violence, journalists decided to use media networks as an outlet. However, with the continuous reporting of such cases and the increasing statistics of electoral violence, the stories behind them are often overlooked.

Interpreting trends

To conduct a more comprehensive analysis of electoral violence, the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism created the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), an online database that analyzes individual attacks based on the dates, targets, and methods. The GTD reported 58.6 percent of unidentified attacks and an alarming increase in assassinations occurred during election periods in the years 2004 to 2017. Notably, post-elections still involved increased cases of violence, which may be attributed to dissatisfaction with election results.

Using the data provided by the GTD as a basis for interpreting common trends of electoral violence, it becomes easier for stakeholders to understand the motivations behind them. For instance, Lund University Postdoctoral fellow Joseph Anthony L. Reyes, PhD, attributed widespread fear to the increase of electoral violence in urban areas.

“If the violence is displayed in the mountains, no one might pay attention. But if it’s in the city, definitely the people might see it and it becomes more effective. The message becomes clearer,” he stated.

This serves as a reminder that, more than the security of locations, the implementation and maintenance of justice systems is what will truly provide protection.

Judicial remedies

While experiences of electoral violence vary across the archipelago, such an event has remained prevalent in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). According to COMELEC Assistant Regional Director Renault C. Macarambon, electoral violence in their locality often occurred between political rivals and their supporters.

Politicians in BARMM are known to integrate electoral violence in their tactics to be able to win the much-coveted seat of power, election lawyer Emil Marañon III confirmed. To some extent, electoral violence has even become normalized in remote and far-flung regions. “Because [candidates] earn money, willing sila makipagpatayan just to actually get that position, and in order to make sure na may continuous cash flow sa personal coffers nila,” Marañon III added.

However, in the rare case that people want to file electoral violence cases, Macarambon explained that their regional COMELEC office’s first step is to make sure that the facts are straight and clear before forwarding it to the COMELEC en banc. The higher poll body would then determine if there is probable cause behind the filed incident, which would merit the intervention of the courts.

Despite the availability of legal procedures, cases are often unsuccessful as people often withdraw in the midst of proceedings. “It’s a question of whether or not people are willing to report and actually [risk] expos[ing] themselves,” Marañon III said. Instead, concerned parties like political clans have the penchant to settle matters among themselves due to their closeness.

Still, the manner in which these tight-knit relationships handle cases of electoral violence only breeds a culture that is harder to regulate by institutions—especially since security personnel could become loyal to local officials. “That loyalty to a certain extent can affect their neutrality in dealing with security issues,” Marañon III added.

Towards peace and order

Noting the issues pervading the country’s electoral system, the solutions that are needed to resolve them are multifaceted and complex. Reyes, for instance, encouraged discernment from stakeholders, “It’s not enough to say that an explosion will happen in some place; the intricacies, or details should also be known.” He then emphasized that the media could be used to provide accurate reports of electoral violence to raise awareness of the violence occurring in their area.

The COMELEC has currently deployed more Philippine National Police and Armed Forces of the Philippines personnel in electoral hotspots, established checkpoints, enforced gun bans, and trained officials in the event of electoral violence. Macarambon expressed that these measures seem sufficient but mentioned that amendments shall be made to the Election Code to adjust to the new technological milieu.

While updating the Election Code is important, Marañon III countered that amendments in the law are useless without proper institutional reforms in the relationship between enforcement agencies and local governments. For instance, security officers should be reshuffled in case they are proven to be partial to their assigned area’s local officials.

Certainly, the extreme nature of electoral violence can only be handled by the government and its policing personnel, as individuals or grassroots organizations are more powerless before terror. However, Marañon III suggested that the government’s solutions should be more area-specific than uniform to be more effective. “Ang common na mali ng gobyerno (the government’s most common mistake) is they would always give a common solution to everything and everyone, without considering these special factors. It’s a paradigm shift that the government managers and security officers need to consider,” he mentioned.

As a predicament fraught with uncertainties and complications, the path towards addressing electoral violence will be no easy feat. However, should this issue be left unencumbered, the country risks itself having a roster of officials elected because of undue fear and not political freedom.