EVERY OCTOBER, malls, stores, and even homes are decorated with cobwebs, bats, skeletons, and jack-o-lanterns. These dark-coloured ornaments are designed to look haunting and creepy whilst still retaining a cartoony playfulness that isn’t enough to scare off young trick-or-treaters.

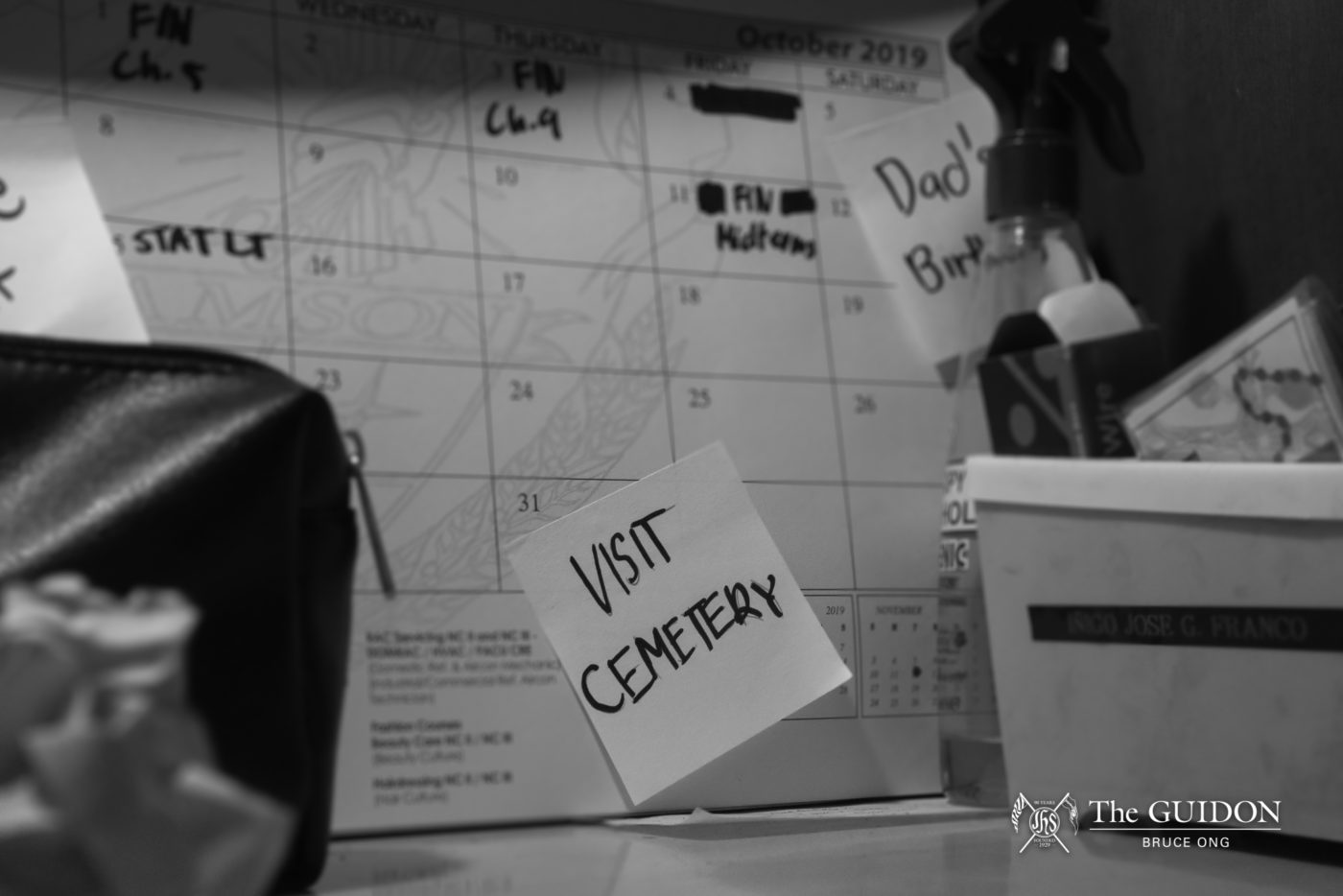

However, besides the playful decorations seen on the 31st, many Filipino families also flock to bus terminals, airports, and highways to visit their departed loved ones and decorate their graves with flowers and candles. With the influence of Western culture on our own, the pre-colonial tradition of visiting the departed—locally known as Undas—has developed among Filipinos and remains rooted in local culture. Though Undas calls for a more solemn celebration, the tradition still shares its core purpose with Halloween: To honor the dead through communal gatherings.

Making holidays closer to home

Before honoring Undas every November 1st, Filipinos gather with their friends and families for some Halloween merrymaking on the eve of October 31st. However, the Halloween that is practiced and widely known today is far from the original celebration of the well-beloved holiday.

The origins of Halloween can be traced back to 2,000 years ago with the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain. Samhain marked the end of harvest and the beginning of winter, which was often associated with illness and death. During the Samhain period, the Celts lit huge sacred bonfires for sacrifices and wore costumes out of animal heads and skins to ward off ghosts. In their culture, Halloween was a sacred and solemn celebration driven by the superstition of ghosts visiting—and perhaps tormenting—the living. However, the grave atmosphere that surrounded the Celts’ Halloween tradition has gradually changed over time.

Much of this change in tune can be credited to America, where the modern iteration of Halloween is said to have originated. Contrary to the Celts, Americans adopted more playful practices for the holiday in the late 19th century like harvest celebrations and the telling of ghost stories for jest. Later on, community-oriented celebrations—such as dressing up in festive costumes, parties, and trick-or-treating—emerged as parents were encouraged by newspapers and community leaders to lessen their focus on the grotesque and mischievous aspects of Halloween.

For Filipinos, Halloween began to manifest in the country in the 1990s through trick-or-treat practices in exclusive villages. The spread of Halloween in the Philippines can also be attributed to the cultural exchange between overseas Filipino workers. According to Sociology and Anthropology professor Albert Alejo, SJ, “[A] lot of Filipinos go abroad and they come back bringing in what they saw being practiced in the West…[With] an influx of OFWs, they bring in all these things.”

The influence of local companies, establishments, and malls also plays a role in spreading and localizing the celebration of Halloween in the Philippines. This is evident through Halloween events that are not only catered to children, but to adults as well. “Halloween is always in the lineup of [company] activities during October [for Shoppee],” Human Resources employee of e-commerce platform Shoppee Shawn Lee says. “Aside from dressing up, it’s an opportunity for the employees to bring their kids to work and have fun with them.”

Partaking in the practice

Though Halloween precedes Undas in the yearly calendar, Undas still rivals Halloween in terms of the efforts Filipinos collectively put towards participation. The scale is evident as each year the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority implements new traffic schemes to accommodate the mass exodus brought about by Undas. As Filipinos head to their respective provinces, they are faced with heavy traffic and long, grueling lines at various transportation terminals.

The faith dimension of Undas is another contributor to its cultural importance in the Philippines with the country identifying as predominantly Catholic. Alejo further highlights that the Catholic Church teaches that people, similar to saints, are merely transferred to the afterlife and not deleted from existence. This mentality, then, explains why Filipinos brave long distances to find their way home for Undas.

Oftentimes, Filipinos’ Undas is defined by the food that family members prepare for sharing with one another during their cemetery visits. Filipinos are also keen to make sure they have offerings, whether it’s flower arrangements or mass intentions. Families who are unable to visit the dead also often opt to light candles on the eve of Undas to leave out on their doorstep.

Our celebration of Undas also shares similarities with holidays and traditions celebrated in other countries. Philosophy Department professor Jovino Miroy, PhD shares one such example: “Europeans go to cemeteries solemnly and quietly remember the truth—that all will die.”

In Mexico, the Dia de los Muertos (i.e., Day of the Dead) has some elements which resemble traditions done during Undas. Dia De Los Muertos celebrations involve offering the dead their favorite food by laying it out on family home altars. Communities also customarily spend the whole night at their local cemeteries to host picnic suppers and play traditional music in honor of the dead.

Tricking the typical

Beyond themed merrymaking and religious responsibility, Halloween and Undas also serve as opportunities for communal gathering. For instance, Halloween is a cause for pause across the nation as friends and families gather to partake in costume parties that take over various residential and professional settings. In the case of Undas, family members near and far do not hesitate to drive—or fly—distances to honor their dead at the cemetery.

With Filipinos placing immense importance on familial relationships, Halloween and Undas serve as a way to combine the two things we love the most: Celebration and reunion. Legazpi City native Kathleen Ong affirms this by delving into the love Filipinos have for observing holidays. For her, our naturally joyful disposition towards life ties into the celebratory aspect of these holidays.

“Family-oriented din tayo. Yung time ng Halloween at yung time ng Undas, yun din yung time na nagcecelebrate yung mga families, nag-geget-together (We’re also family-oriented. Halloween and Undas are times for families to celebrate, to get together),” Ong adds.

This concept of kapamilya or family manifests differently during Undas and Halloween. While honoring the dead during Undas, the borders between families tend to dissipate and the whole cemetery forms a new, tight-knit community that is—however briefly—united by the solemn and commemorative purpose of their visits.

Ong says, “Kahit hindi namin relatives, basta kilala ng parents ko o grandparents ko, pumupunta [yung mga kamag-anak ko] doon sa mausoleum nila (Even if we are not related, as long as my parents or grandparents know them, my relatives would still visit their mausoleums.)”

On the other hand, Halloween offers a more celebratory form of social bonding. Alejo asserts that Halloween events and festivities provide opportunities for barkada (i.e., a group of friends) reunions as well. “It adds a new layer to [one’s] social, cultural and emotional capital…It adds a new layer of relationship,” he says.

Whether one goes trick-or-treating or visits the local cemetery, Halloween and Undas emphasize the importance of intimate human connection amidst repetitive work-filled schedules. These traditions give individuals the opportunity to strengthen their bonds with loved ones, especially those who they rarely get to see through the rest of the year.

It all amalgamates to show that, in spite of death, we never fail to celebrate life with those we love and those who have left us. The holidays dedicated to our departed remind us that as darkness settles in, the candle lights that we leave on loved ones’ tombstones continue to shine on—their flames persistently flickering throughout the night.