Is it really more fun in the Philippines?

LAST JANUARY, the overwhelming response to the Department of Tourism (DOT)’s “It’s More Fun in the Philippines” campaign proved that our national identity is more than “enough.”

History attests to this. As a result of the galleon trade during the 16th century, Manila had become a truly global city long before most parts of the world. However, even with a resource pool spanning more than 7,107 islands, the Philippines has yet to fully harness its most powerful resource: the Filipino.

Ugly duckling

For most of its history, the Philippines has lived in the shadows of its colonizers—and this is precisely the reason that society points to for our lack of a solid cultural identity. Compared to other countries, the Philippines seems to have had less time to let its roots run deep.

Online activist Jay Jaboneta, recognized internationally for his Yellow Boat Project, which sends children in Zamboanga to school, says, “We’re still trying to find ourselves in the mess. Fifty years [of formal independence] seems like a long time, but if you compare it with Europe they, have thousands of years already. That’s a long time compared to us.”

On the other hand, Professor Fernando Zialcita, PhD of the Sociology and Anthropology Department points out that the Philippines shares the same circumstances as Hans Christian Andersen’s story of the ugly duckling. He says, “The problem in trying to identify who we are is that we keep trying to fit the Philippines into categories that don’t fit.”

In the Asian context, the Philippines is not a duck, but a swan. “Our Asian neighbors say that we’re not Asian enough. But why should we care?”

Lost in translation

It was the galleon trade that led British author David Irving to describe Manila as the world’s first cosmopolitan city. Manila was where the four continents—Europe, Asia, Africa, the Americas—met. Zialcita echoes the same sentiments, and laments, “Because of its international character, the destruction of Manila in 1945 is a loss not only for the Philippines but for mankind.”

Rather than being a source of frustration, the nation’s multicultural past is, in fact, part and parcel of the Philippines’ competitive package. It’s a history that confers on the Filipinos a certain cultural openness less present in other Asian societies, and extends our borders as an intercontinental meeting place.

Unfortunately, this global edge has often been lost in translation, with a lack of consistency and continuity in branding our tourism campaign. There is no bridge that connects the campaigns spearheaded by successive DOT secretaries, such as Fiesta Aisles, Wow! Philippines and Pilipinas Kay Ganda.

“The propaganda wasn’t very clear about what we wanted to preserve about ourselves. There was no selling point. We didn’t cultivate a brand image,” explains Zialcita.

Impression management

Unlike the Philippines, our Asian neighbors know how to aggressively brand themselves, not only through words but through imagery.

Anna Oposa, internationally recognized for her fight to “Save the Philippine Seas” says, “When I was in Davos, Switzerland, there were Incredible India ads everywhere, even in a snow capped mountain!” For her, what other countries have is focus. “They know what to sell. Our past tourism campaigns lack that.”

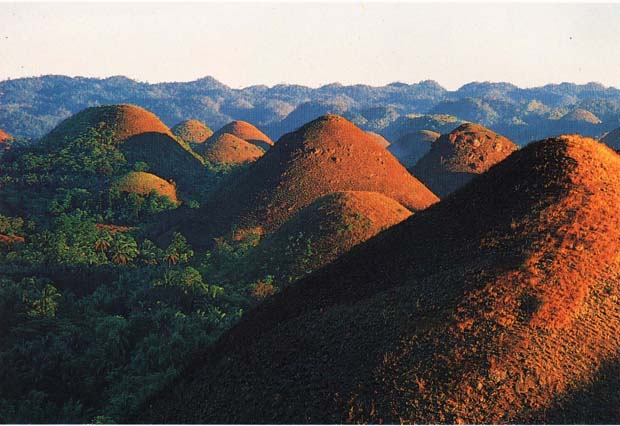

Zialcita says that in India, “One film sequence will show you red as manifested in different spheres of Indian culture,” whether it’s in the palaces of Jaipur or in the colors of the desert. “[But] in the Philippines, we haven’t decided if it’s Banaue, Palawan or Boracay, so I think that’s probably where we can improve as well.”

Is it really more fun?

As the social networking capital of the world, the deceptively simple new slogan, “It’s More Fun in the Philippines,” works in the Philippines because it caters to the Filipino’s creative and celebratory spirit. “It’s anchored on people. You can see the strength of the Filipinos on Twitter and Facebook. It works because the multicultural aspect makes us more open than other Asians,” says Jaboneta.

However, Filipinos must not let the overwhelming hype in cyberspace blind them from seeing the real conditions of their country: still developing, congested and polluted.

“It’s true that we’re creative, but I’m just saying that those are high moments. But most of the time, if you are trying to walk around Manila from point A to point B, you are going to get pissed off. Where’s the fun in that?” says Zialcita. There’s a stark contrast between what tourists hear about the Philippines and what they will see upon arriving in the Ninoy Aquino International Airport, which is, after all, known for being one of the world’s worst airports.

It may indeed be more fun in the Philippines, but for whom—the foreigners, the natives, or both? Although it sounds shallow, the simple fact is that tourism relies heavily on first impressions. It’s what hooks tourists to dive deeper into the experience of a new culture. As such, Oposa says, “When someone says the Philippines is dirty, that the traffic is horrible, we shouldn’t attack that person. We should examine the situation and ask ourselves ‘Okay, what do we do now?’”

Meanwhile, Zialcita warns, “Words mean a lot especially in a campaign. If you don’t choose your words carefully, you might raise expectations that will not be met.”

Jaboneta, however, sees that expectation as a challenge. “I think it’s a subtle call for every Filipino to invite tourists to come to the Philippines. The expectation not only falls on the shoulders of the government and the DOT, but also on every Filipino,” he says.

How do you become Filipino?

Undeniably, the Philippines still has much growing up to do, especially with developing its infrastructure. However, the DOT campaign has generated the necessary demand for the investment on something more valuable than mere economic benefits—sentiments and ownership.

The ability to rise to People Power is more of a Filipino trait and less than just a moment in history. Jaboneta says, “My advocacy is to promote that [People Power] isn’t just for ousting leaders or changing governments. We can use it every day.” With over 11 million Filipinos abroad, he says, “If each one brings home one friend every year, we’ll have 11 million tourists. Of course, that’s easier said than done—but even if just 1% takes that seriously, then that’s already one million.”

Although the Philippines is struggling to discover its cultural identity, Oposa reminds us that it is “not about what is Filipino, but how something becomes Filipino.” And that mindset begins with realizing that it is great to be diverse.