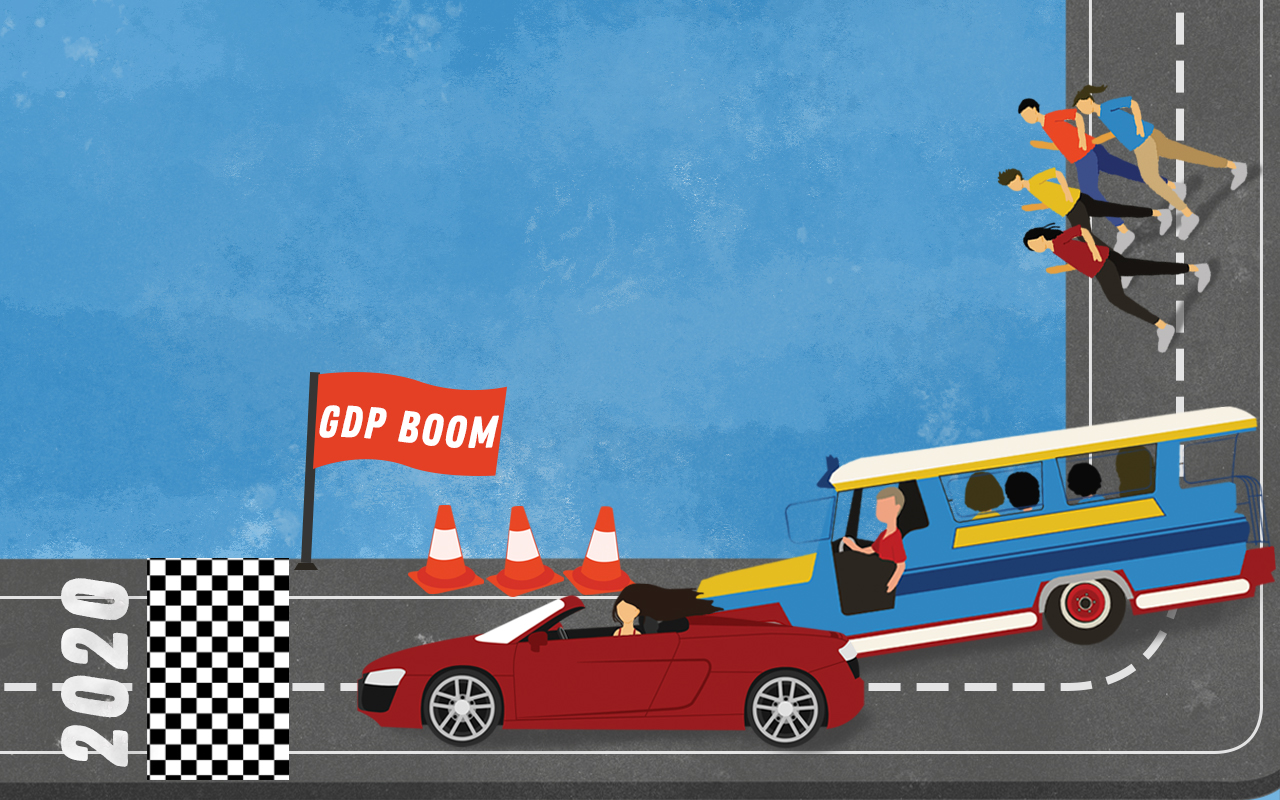

DUBBED AS Asia’s rising tiger by the World Bank in 2013, the Philippine economy experienced an upward turn in the 2010’s. In the past decade, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) rose from 199.59 billion US dollars (USD) in 2010 to 330.91 billion USD by 2018. So promising and rapid was the country’s economic growth that in 2015, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation even predicted that the Philippines would eventually rank 16th among the world’s largest economies by 2050.

Amidst this growth, 16.6% of the country’s population still live under the poverty threshold, according to 2018 statistics from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). In fact, the poorest 20% of the Philippine population never held more than 6% of the country’s total wealth between 2010 and 2019, while the richest 10% controlled almost 40% of the Philippines’ total wealth in the same period. Thus, it is no surprise that the country only obtained a Gini coefficient score—the statistical measure of income distribution in a given country—of 44.4 according to 2015 data from the World Bank.

Despite claims that the Philippines is moving past the disastrous economic conditions it faced in the past three decades, the country’s most vulnerable strata continues to lag behind. A closer look into the country’s social context reveals a system wherein economic development benefits only the rich, while preying upon the poor and working classes.

Lack of social services

In the 1980s, the economist Amartya Sen pointed out how a country’s GDP only measures “commodities” and not “capabilities” such as obtaining healthcare, sending children to school, or even providing shelter.

Evidence of this exists in contemporary Philippines. Statistics relating to social welfare indeed show a nation that has yet to translate monetary wealth into higher standards of living.

For one, statistics from the 2019 Philippine Wellness Index reflect that 40% of Filipinos believe that they cannot afford to pay for healthcare. This is despite the rise of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation as the supposed financier of the national healthcare system.

Another rampant concern is education, which is only accessible to 5 out of 10 Filipino families.. A multidimensional poverty index created by the PSA in 2018 detailed just how prevalent the problem is: Among several social issues—like hunger, unemployment, and sanitation—lack of education was the most widely felt by Filipinos.

In the same report, security of housing was revealed to be another serious problem faced by Filipinos. According to the Commission on Audit, the National Housing Authority had only constructed 52% of planned housing units under the Aquino administration’s Php 50 billion housing project.

Housing needs remain unmet, as even under the Duterte administration, private profit remains to be the utmost priority.

“Our real estate industry may be booming, but we’re doing poorly when it comes to sheltering our people,” Senator Sonny Angara stressed. He warned that unless the administration spends more for housing, the number of homeless Filipinos could reach crisis proportions.

Stagnation in the labor sector

Apart from subpar social services, Filipinos also struggle against a harsh labor structure. According to the Global Workers Rights Index of 2018, the Philippines is among the top ten countries with the worst working conditions for laborers.

Labor contractualization is one of the biggest grievances of Filipino workers as it prevents them from reaping the full benefits of employment. This is because they are employed on a “5-5-5 scheme,” wherein contracts last for five months at a time, baring contractual workers from social services and benefits regular employees are entitled to. Moreover, contractual workers are vulnerable to dismissal at any time, which many companies abuse to justify unpaid overtime, iniquitous compensation, and other measures that increase their profit margins.

Working Filipinos have long been desperate for an end to contractualization—so much so that the Trade Union Congress of the Philippines and the Alliance of Labor Unions, two of the country’s biggest labor organizations, endorsed President Rodrigo Duterte in the 2016 elections as he promised just that.

However, Duterte appears to have reneged on his word. Last year, he vetoed the Security of Tenure Bill, a groundbreaking legislation that would have prohibited all forms of contractualization.

With their hopes dashed, union workers have taken to the streets, demanding the fulfillment of their rights under the Labor Code of the Philippines. However, protests were met with layoffs, arrests, and violent dispersals.

Aside from contractualization, the labor sector is also contending with the stagnation of the rate of minimum wage. In the National Capital Region’s (NCR), minimum wage falls between Php 500 to Php 537 per day—a mere Php 100 increase from its 2010 value. Other regions are even worse off, with minimum wages amounting below Php 400—NCR’s approximate minimum wage at the start of the decade. These figures are far from the estimated value of living wage, which stands at Php 1,014.

The disparity between minimum and living wages highlight another dimension of income inequality: That it favors a select few who, more likely than not, are from Metro Manila. Moreover, a report from the Asian Development Bank found that less than half of Filipino workers earn a living wage, as the current minimum wage is below the living wage.

Progress for a minority

Most initiatives that have been launched over the past decade to improve socio-economic welfare in the country focus on infrastructure development. Aquino’s term bore witness to the construction of major expressways and airport terminal extensions and facilities that are mostly used by middle to upper class members of society and by businesses who need to transport products. President Duterte’s flagship Build, Build, Build Program features much of the same.

Yet, none of these have succeeded in addressing income inequality because they are predicated on the same problem they try to solve: Much of the Philippines’ infrastructure development has come at the expense of the poor. For example, widespread displacement—be it of the urban poor or indigenous peoples—is a common consequence of these infrastructure projects.

More than that, these platforms are hardly beneficial to the country’s impoverished population in the first place. Better roads, more highways, and expanded airports do not mean much to Filipinos who cannot afford cars, airfare, or even a secure home that the government cannot take away.

Faced with all these issues, the Philippines’ status as Asia’s rising tiger may seem cheap and impudent. It praises growing wealth that is in the hands of only a few and progress that has not been felt by the sectors that badly need it most. The marginalized and oppressed have remained poor and neglected—and much still needs to be done before they can be called on the rise.